Dispatches from a Contested Utopia

There is a vision of Puerto Rican beauty.

There is a Puerto Rican faith.

A faith that goes beyond the eternity of generations not yet born…

—Pedro Albizu Campos (1893-1965)

Walking on one particular strip in the Midwest, you feel a connection to the heartbeat of La Cordillera Central and the large waves crashing against the island shore. As you continue, amid pulsating rhythms y el aroma de recao, you hear the chatter of people discussing la brega. Together, this vortex envelops you con la esencia de Puerto Rico. But, it’s not Bushwick, North Philly, or any artery in El Barrio. You’re over 2,000 miles away from San Juan, on the west side of Chicago.

Over the past 60 years, this determined Boricua community struggled against redlining, gentrification, and structural racism to save a neighborhood we call home. Here, Puerto Rican pride is on display, every day, steeped en la cultura viva y el orgullo de ser puertorriqueños.

How does this happen? Pues, bregando y haciendo de tripas, corazón.

Wanda Colón López opened Café Colao in the section of Chicago known today as Paseo Boricua. Born in Chicago, she created the space para rendirle tributo a Mita, her grandmother. This tiny woman with little to no formal education signed her name with an X for most of her adult life. Because of this, she made sure her children and family were educated and prepared for the struggle. Mita’s home always smelled of freshly made cafecito colao and she generously offered a cup to anyone who came to visit. Aiming to recreate that feeling, Wanda fashioned her locale inspired by the panaderías típicas where locals could linger freely for hours. Always, people come in and share the ups and downs of their latest brega. “La brega,” Wanda says, “means trabajo y la lucha. Those stubborn obstacles, random or systemic, that we have to work around just to get through the day-to-day.”

By and For Boricuas

Stories like hers inspired a new seven-part podcast series, entitled La Brega: Stories of the Puerto Rican Experience to offer an entryway for both Puerto Ricans and its diaspora to engage in new and nuanced conversations. Unmediated by bias, fetish, or otherizing, this anthology, created by and for Puerto Ricans, reaffirms the need for reporting imbued with historical facts and personal, lived truths.

Helmed by On The Media’s Alana Casanova-Burgess and produced by WNYC Studios and Futuro Studios, the podcast is available in both English and Spanish and enters the media landscape at a time where people are living virtual, interconnected lives. La Brega offers an array of perspectives with voices of present-day Boricuas rarely heard in mainstream media.

¡Ay! ¿Qué será de mi Borinquen cuando llegue el temporal?

For many, the story doesn’t change.

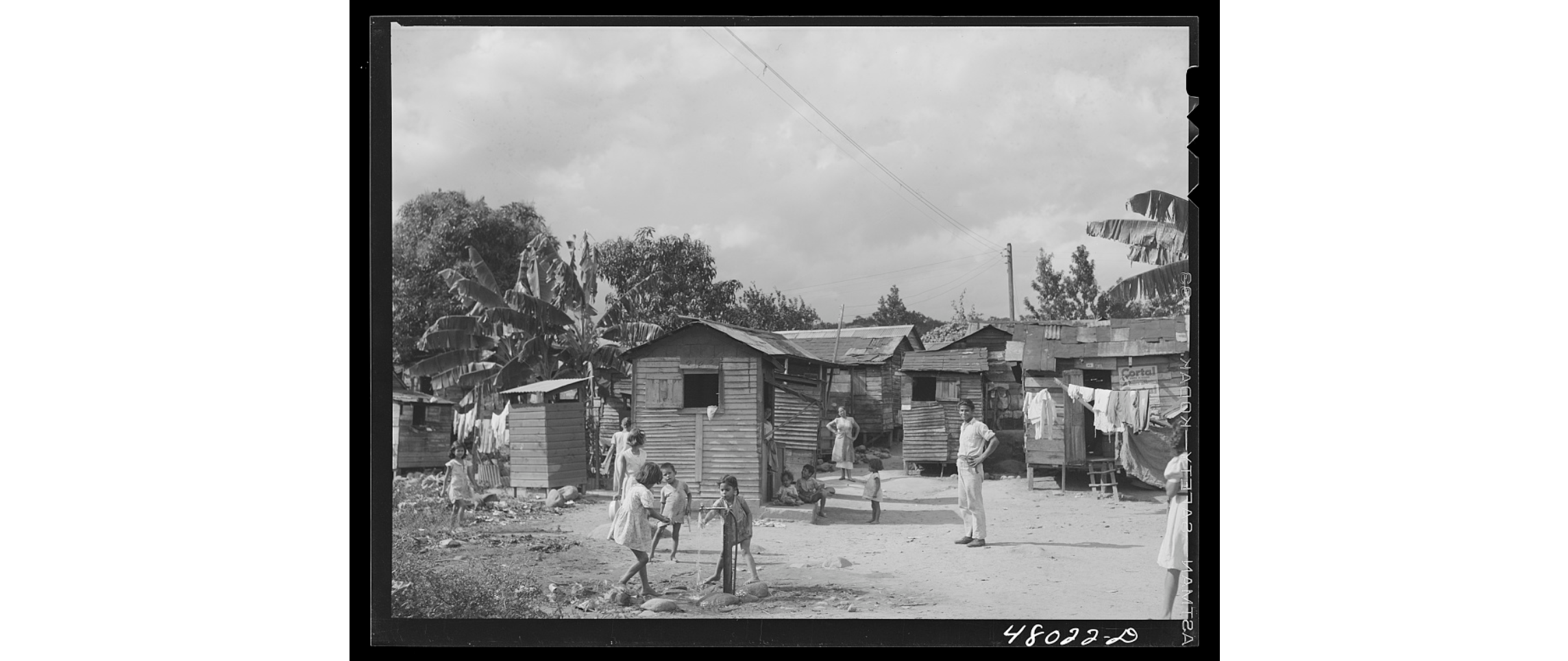

In the early part of the 20th century the devastating hurricanes, San Felipe and San Ciprián, ravaged the island amid deep political and economic crises and revealed the interconnectedness of infrastructure, environment, and public health. La Brega reminds us that back then, the average life expectancy was 46 years, and 70 percent of the people lived in the countryside without running water. Electricity, including the installation of telephones, from the turn of the century to the 1930’s, was implemented first to benefit sugarcane irrigation and operations. In many towns, even as late as the 1940s and 1950s, there was only one phone for an entire neighborhood. Decades later, Maria made landfall under similarly precarious conditions.

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: San Juan, Puerto Rico. In a dress factory]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e540f30394fe70075c1ccd6/1614349848703-A0MEDAETCZFAVJBYL1EP/service-pnp-fsa-8c08000-8c08900-8c08914v.jpg)

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: San German (vicinity). Farm laborer's family in the hills]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e540f30394fe70075c1ccd6/1614349965445-MU5A6RZPQF52S8FUVOQQ/service-pnp-fsa-8c08000-8c08700-8c08781v.jpg)

Like la plena puertorriqueña, el periódico cantado, or sung newspapers, of el pueblo which took hold of the island circa 1900, communicated stories and events with empathy, humor, and even satire. Aspects of everyday life were featured in the lyrics of popular plenas such as “Cortaron a Elena,” and the hurricane-themed, “Temporal.” Among the poorer, less literate classes, la plena, and its improvisations were how stories and el chisme del vecindario traveled.

Operation Bootstrap, an economic development strategy implemented in the 1950s and 1960s to modernize the island, chased industrialization for progress and profit by engineering a shift from agriculture to manufacturing. Government programs gave tax breaks to U.S. companies, but for this model to work, the island needed to strike the right balance between jobs and laborers. Economists projected that one million Puerto Ricans needed to leave, prompting a massive migration of Puerto Ricans seeking work in industrial zones across the U.S. in search of “a better life.”

This trajectory, depicted in La Carreta, the 1952 book by Puerto Rican writer René Marqués, follows the story of a family of jíbaros, or rural peasants, who move from the countryside to San Juan and end up in La Perla (an infamous neighborhood that gained international attention through the 2017 hit song “Despacito”). Later, the family is dispossessed and displaced in a New York City ghetto. They return to the island when the story’s hero suffers a fatal accident while on the job. In dialogue with Marqués, the late poet Tato Laviera’s La Carreta Made a U-Turn, a landmark Nuyorican book, follows up with the story of a family that does not return to Puerto Rico—revising a cautionary tale and negative connotations of the diaspora into a story of adaptation and perseverance.

“I’m one of the lucky ones,” says Rosalba Rolón founder and director of Pregones/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater. She remembers moving to New York in the 1970s, after having graduated college in Puerto Rico noting that “Calls back then incurred long-distance charges. These could quickly add up to be cost-prohibitive.” To stay in touch with her mom, she wrote letters, many letters, and saved for two 20-minute phone calls to Puerto Rico per month. Photographs kept her family and Puerto Rico close to her heart. Rosalba recalls, “I could afford to travel two times per year. I delighted in surprising my parents with my unannounced visits. The yearning for Puerto Rico, for me personally, was not an obstacle. I knew that Puerto Rico was only three and a half hours away.” She adds, “However, I always remember what Luis Rafael Sánchez, author of La Guaracha, once told me: Puerto Rico is a place that when I am there, I can’t wait to get out of; and when I’m here, I can’t wait to go back to. Pero, allí estȧn mis muertos.”

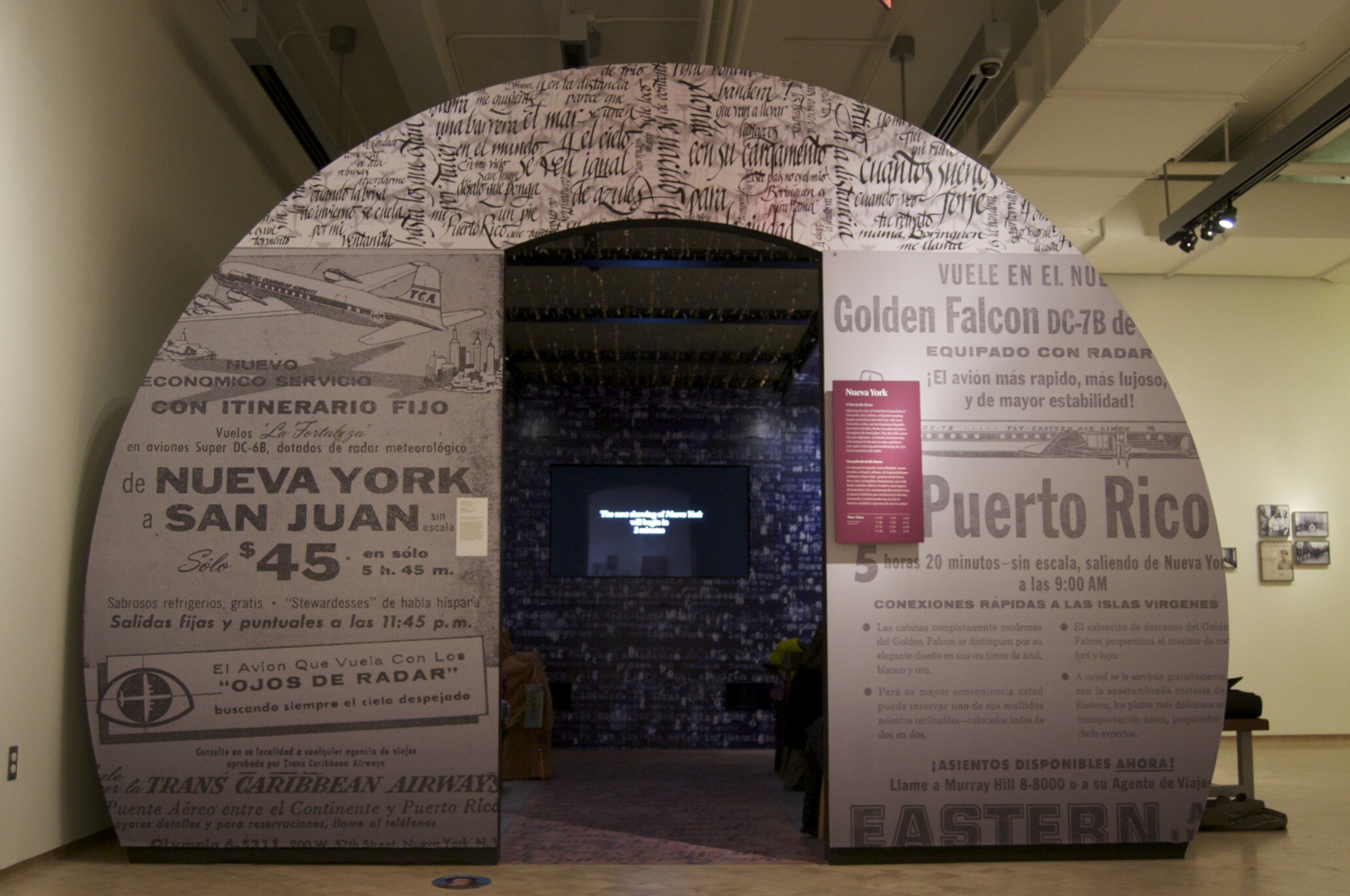

That pull of the island is real.

Modern travel afforded by la guagua aérea, the flying bus, facilitated for some in the diaspora the ability to go back-and-forth and remain in contact with family and the island. But this vaivén was not financially feasible for many working-class families like ours in the Midwest. Some wise mothers had the foresight to save enough to cover a flight in the event of a family crisis or to mourn with family over the death of a loved one. For the most part, letter writing, photo exchange, and cards were the primary means of sustained communication. Long-distance calls were costly and those were infrequent. How many times did a phone call from Puerto Rico generate excitement only to give way to trepidation? ¿Con que estarían bregando? It could be anything and it was always something. It is part of our lived realities, impacting us all, all the time.

Puerto Ricans are always en la brega, vulnerable and alert

—Arcadio Diaz Quiñones

Regardless of political inclination or affiliation, Chicago Boricuas share an identity with the island that is regenerative—circular and constant. Cultural nationalism was all around us and most evident by the schools in our community named after Juan Antonio Corretjer, Pedro Albizu Campos, Roberto Clemente, and Dr. Antonia Pantoja. In 1966, the killing of a young Puerto Rican man incited an uprising and conflict with the police that marks us to this day. Moreover, 11 of the 14 imprisoned Puerto Rican nationalists pardoned by former President Clinton were from Chicago or had deep Chicago ties.

The Puerto Rican Agenda, now a formal nonprofit in Chicago, began as an ad-hoc group of leaders who came together to organize and strategize around local, regional and national issues, such as the Chicago 21 Plan; voter education in Orlando, Fla., and the U.S. military occupation of Vieques, an island off Puerto Rico’s eastern coast. It also speaks truth to power about failed policies like the Jones Act, the deplorable treatment of our people after Maria, and the international movement led by Professor José López to free his brother, Oscar López Rivera, a Puerto Rican nationalist released from jail after 35 years. Both men are Wanda’s uncles. She will never forget the day Mita implored, “No dejen que mi Oscarito se pudra en la cárcel. Él no puede morir allí.”

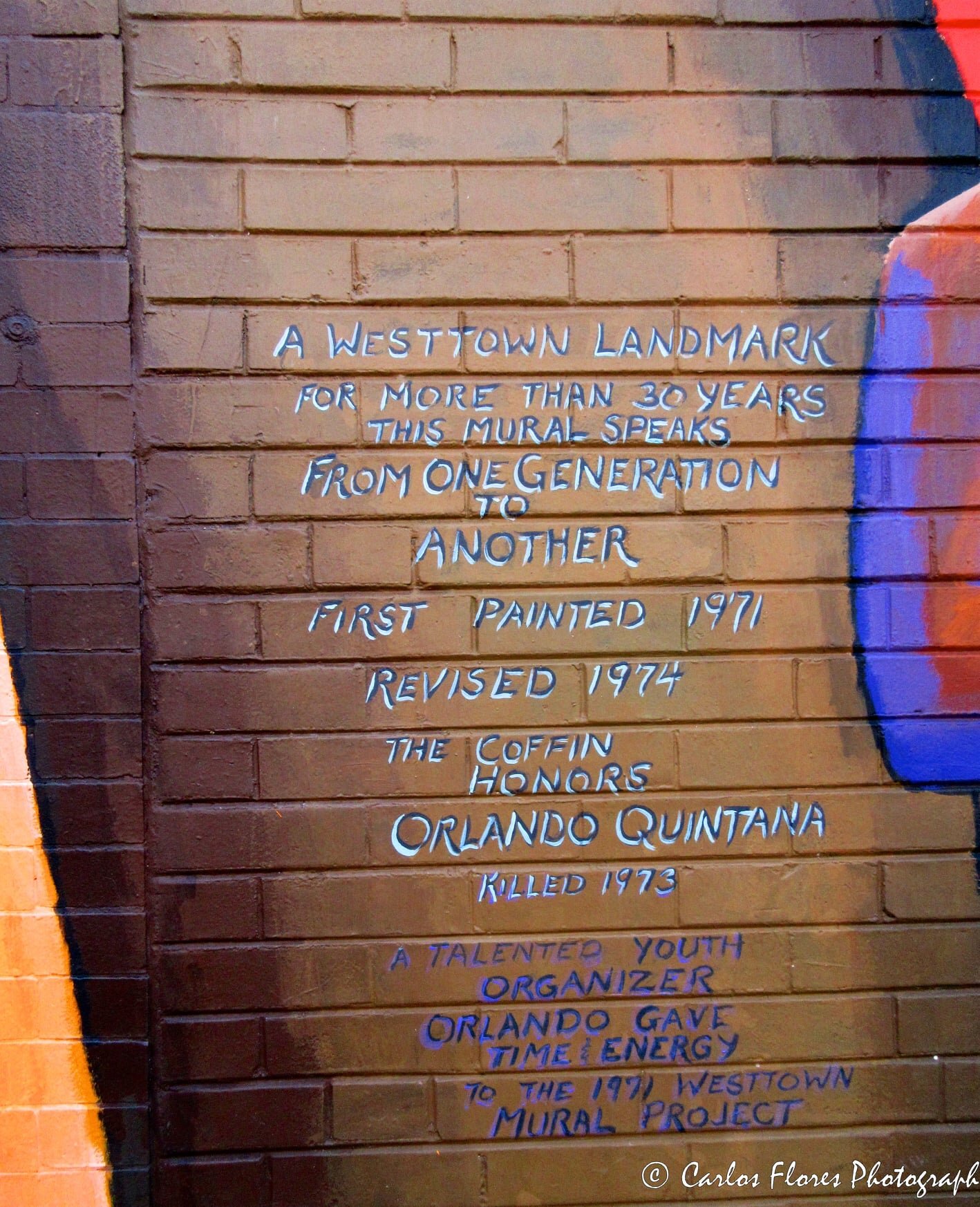

Following the 1966 uprising and community protests, the emergence and influence of the Young Lords, the ubiquitous presence of The Latin Kings, and when Puerto Rican nationalists went underground, it seemed the whole community lived under the threat of over-policing and surveillance. People had to be careful; the homes and phones of many were bugged. And in spite of all this and more, the community’s core values have kept us together.

Our community’s veneration of the life and legacy of Pedro Albizu Campos, an independence icon, and the desire to install a public monument to memorialize him in Humboldt Park stirred debate and controversy. José López organized a protest at a public meeting that ultimately denied our community monument in honor of Campos. A series of tense political negotiations led by councilman Billy Ocasio and city officials ensued. To assuage the community’s discontent, city officials approved the installation of two 59-foot-tall Puerto Rican flags to serve as gateways to Paseo Boricua.

“... Part of La Brega is imagining a better reality, together.”

—Arcadio Diaz Quiñones

Decades of organizing with fidelity to community advancement, the right to a life with dignity and self-determination, transformed Paseo Boricua, a once disinvested area into one which boasts 70 percent occupancy with properties and businesses owned and operated by Puerto Ricans. Despite these successes, the Boricua population in Chicago is shrinking. Seeking affordable housing and employment, many have moved to the suburbs, exurbs, and cities like Cleveland, Milwaukee, Houston, and Tampa and Orlando, Fla. There are some who still dream of returning to Puerto Rico, while others can’t fathom leaving their children or grandchildren in Chicago behind. Those of us that can, fight to remain in our neighborhood and for justice for our homeland.

“La brega is our existential condition.”

—David Gonzalez, Nuyorican journalist and photographer

La Brega: Stories of the Puerto Rican Experience, available in English and Spanish, is a co-production of WNYC Studios and Maria Hinojosa’s Futuro Studios.

Author’s notes:

Wanda Colón and I want readers to know that we’ve been friends since high school and we used to dance salsa in the school hallways blasting Eddie Palmieri’s “Puerto Rico” which used to drive the nuns nuts.

The 101st General Assembly of the State of Illinois is considering a piece of legislation that will be introduced the week of March 1, 2021, followed by Committee hearings that will culminate on May 31, 2021, to make official the designation of this community anchor as “Puerto Rico Town.”

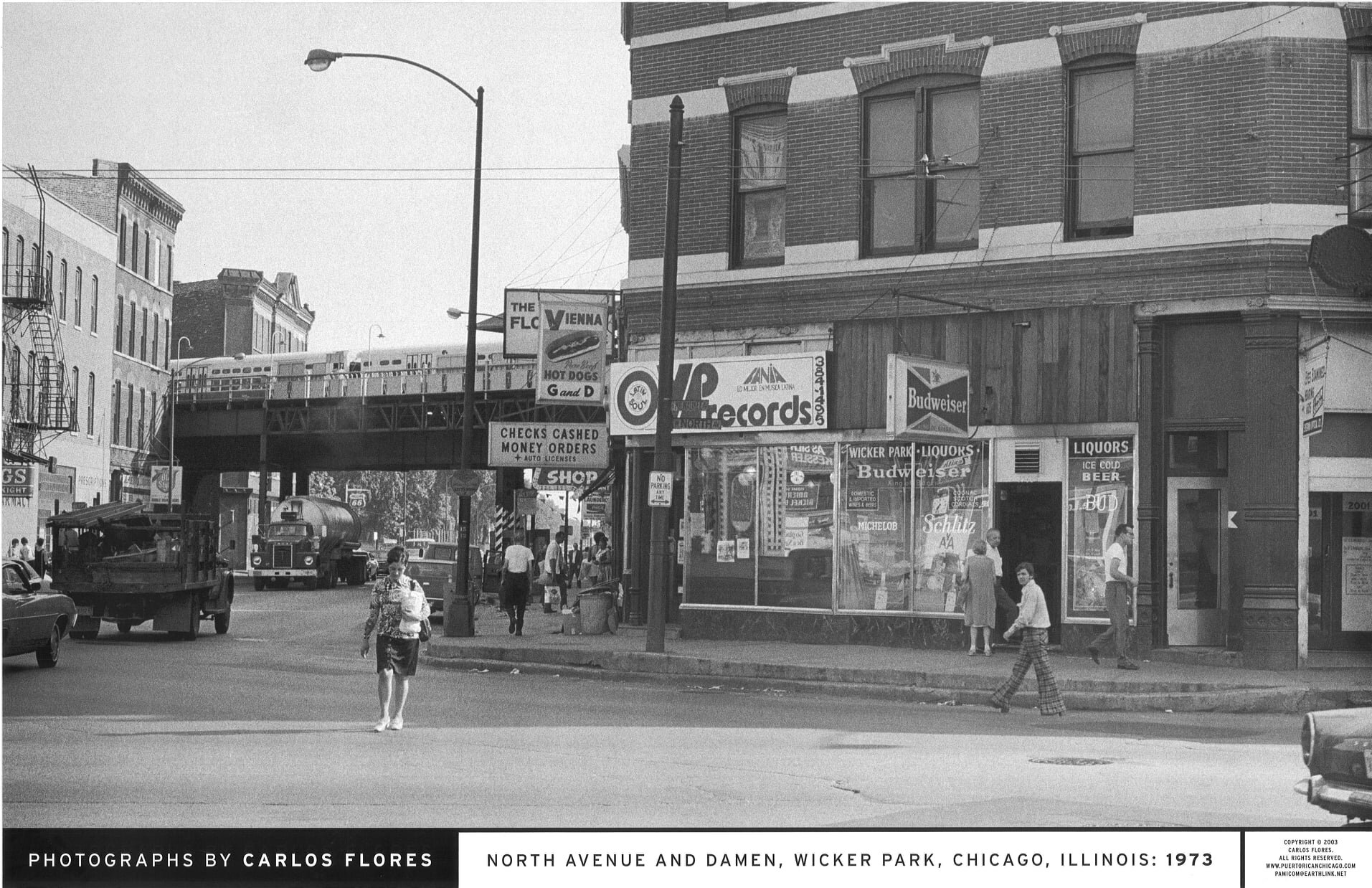

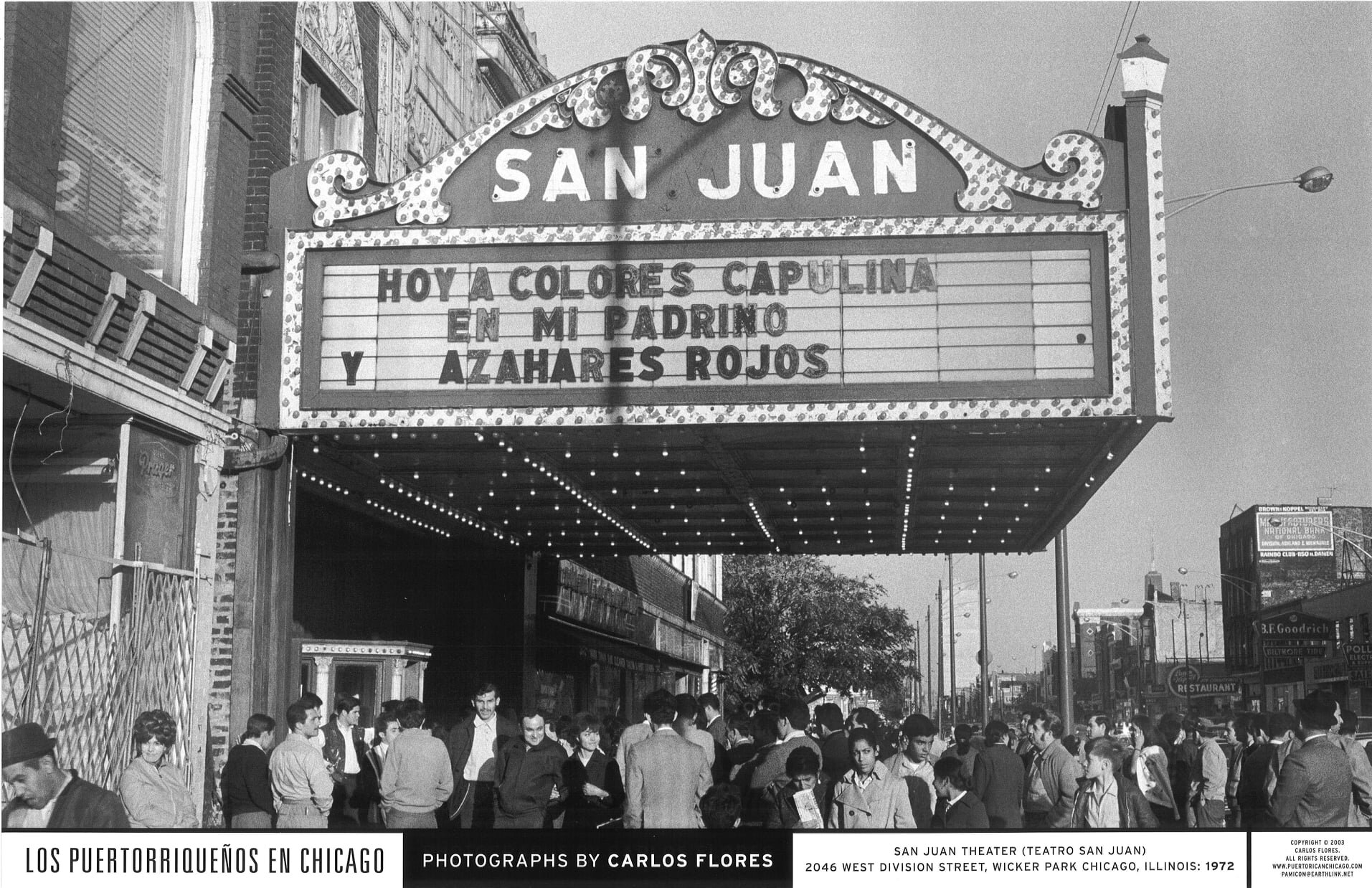

Carlos Flores has been documenting Chicago’s Puerto Rican community for over 45 years. His work is featured in Elizabeth Ferrer’s book, Latinx Photography in the United States: A Visual History. A cache of his images, news clips, album covers, and more can be viewed in Puerto Rican Chicago.

PRAA, Chicago’s Puerto Rican Arts Alliance partnered with the Chicago Collections Consortium to provide public access to its vast photographic archive, visit “El Archivo Project.”

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Wanda Colón López, owner, Café Colao; Mariposa Fernandez; Carlos Flores; David Galarza; David Gonzalez, Erica Gonzalez; Fernando Grillo, Esq., CEO of Aspira IL; Eliud Hernandez; Antonio Martorell; Oscar Molina; Maria Teresa Román; Billy Ocasio, CEO and president, National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture; Rosalba Rolón, founder and director, Pregones/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater; and, copy editor, Tania Lambert for your generosity and support.

Neyda Martinez Sierra, an associate professor in The New School’s Department of Media Management, is producer of the documentary films LUCKY and Decade of Fire.