Post-fire Technologies: Elsa Muñoz’s Future Flowers

In “A Map to the Next World,” former U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo describes a transition between a fourth and fifth world. Pulling from a Pueblo origin story, she identifies things one might see in celestial limbo like a membrane of death, a map made out of sand, children-stealing fog, and flowers of rage. Chicago artist Elsa Muñoz references these delights in one of her new paintings called Flowers of Rage (After Joy Harjo) (2024), which depicts a lilac-colored flower in front of a dried, hill-like landscape that at times resembles the silhouette of a human’s back.

Premiered in Muñoz's solo exhibition Botánica Apokalítica at the curatorially focused gallery Pecha Projects in Columbus, Ohio, this work is part of Fire Followers, a new painting series that draws from a plant species of the same name (commonly called fire followers). Thinking about the relationships between ecology, body, and spirit, Muñoz's ongoing practice and new exhibition speaks on the intercorporality of systems. They surface how rage, grief, and violence can be marked in ecological and spiritual fields. How painting, and by extension art, as a technology can help achieve a journey from imbalance to balance; from disenchantment to reconciliation.

Muñoz uses fire-following flowers as testimonies of how tied things are; how ecology, body, and spirit interlaces with one another. Used in herbal medicine and in social/sacred rituals, the fire-following plants come out of forest fires or controlled burns, which was an important subject matter to the artist in a previous series. Historically, Indigenous populations of given regions practiced controlled burns, also known as prescribed fires, to create a domino effect of conditions for an ecosystem’s health to regenerate. Through smoke, ashes, and heat, the burns reduce fuel for wild fires, eliminate invasive vegetation, and develop an atmosphere for seed germination.

Suppressing these fire practices leads to droughts like in the paramos of Colombia or escalate fires like in California. Post-fire, the charred site becomes a habitat for creatures to forage and the fire-following flowers to bloom. Fire followers are souvenirs of these microcosms and phenomena. They hold the gestures and actions of the site experiencing itself; trying to balance itself after the loss of mass and matter. Muñoz turns to painting to translate these seen and unseen events, these actions and reactions, in order to animate the flower’s properties as fire-created medicine.

Muñoz’s renditions of these fire-following flowers are dynamic buds growing within red burnt atmospheres. Using panel, linen, and canvas surfaces, the paintings sway between definite and abstract, constructing dreamlike scenes of speculative ecologies. The leaf’s color spot in Fairy Slipper Orchid (2024) is meticulous, but in Rabbit Brush (2024) the flatness of the white branches are unsettling and wild. Most moments in the series are impressionistic and fluttery like the bells in Coyote Tobacco (2024) or highly saturated like in Desert Bluebell (2024).

Formally trained in oil painting at Chicago’s American Academy of Art, Muñoz is currently more concerned with the vulnerability and agency of medium expansion rather than the mastery of realism. Taking notes from the macabre of Ivan Albright and the sublime of J. M. Turner, the history of (flower) painting is inherent and the urgency for floriography suspended. Muñoz offers to add honest associations to Indigenous plants as sights of beauty and complexity, taking them out of scientific colonial studies that pressed them in botanists’ journals. Perhaps the only formal symbolism apparent in the series is the poppies, such as in Fire Poppies (2024) and Prickly Poppy (2024); art history associates the poppy flower with war, sleep, resilience and death. And like all purist painters, Muñoz believes in how painting serves as a technology to raise consciousness, indoctrinate values, and, seditiously, to enter an exorcism.

Curated by art advisor Michelle Ruiz, the show’s title pulls the etymologies of botanica, a religious shop or botanical garden, and “apokaliptica,” the Greek root word for apocalypse meaning revelation. Outside the biblical sense and dissociating her work from images of global ecological crisis, Muñoz’s apocalypse is more akin to Grace L. Dillon’s summarized “Native Apocalypse” from the 2012 anthology Walking the Clouds. Dillon explains Native Apocalypse as being in a state of “aakozi,” the Anishinaabemowin word for being out of balance and sick. In Native context, it is an imbalance initiated by colonization projects that separated spirit out of the human body and out of ecological kins; in Modernism, it’s the disenchantment process caused by Western sciences. This point of flux is where Muñoz positions her work. She proposes paintings and sculptures as technologies that can initiate a journey from imbalance to balance—to enchant oneself again.

Critically and moving beyond notions of gentle folk medicine, Muñoz’s flowers are much more metaphors of rage than to healing. Studying theories ranging in the psychospiritual, eco-somatics, and mind-body practices, Muñoz subscribes to the belief of writers like Bessel van der Kolk and Donna Haraway who argue that trauma embeds itself in a body’s nervous systems and also echoes itself in ecological and spiritual planes. Thus, one can imprint an interior trauma like grief and rage into an exterior spatial field. With this in mind, Muñoz hopes her work locates the viewer's rage, violence, or grief to not only help with personal reconciliation but also global levity.

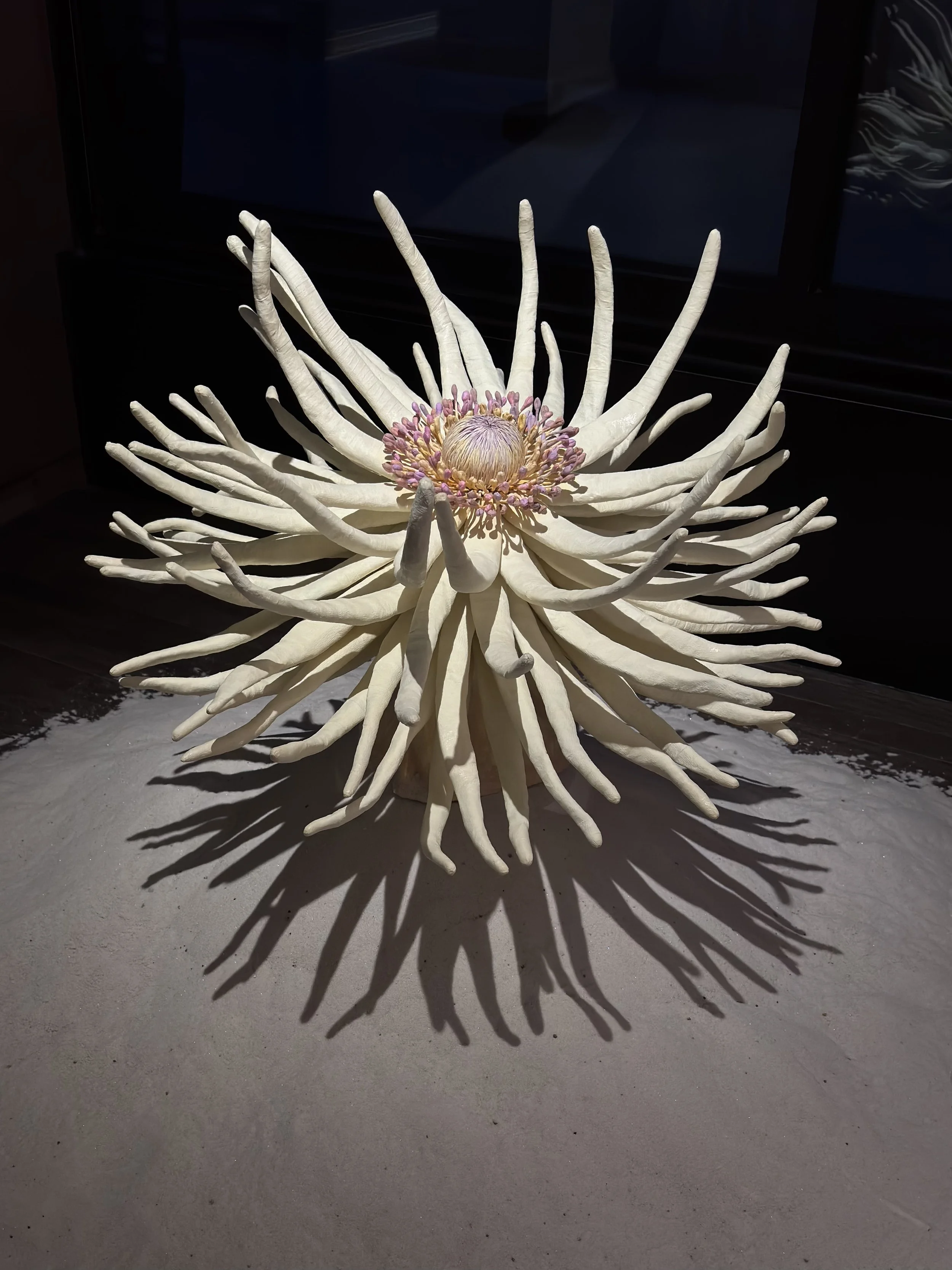

Using storytelling and speculative fiction, Muñoz also debuted a series of sculpture works titled Future Flowers that she made in collaboration with Madrid-based artisanal studio Níkua and artist Indira Sánchez Yiyagami. Using clay, paper, and paint, this delicate sculpture series are flowers with hybrid marine and desert-like characteristics that speculate the form and function of future plant species. Narratively, due to a chimera make-up created by spiritual and material endurance, these creatures have evolved self-autonomy, pride, and consciousness to withstand a variety of extreme travels and environments. Calling it botanical futurism as a framework to think through this transmutation of deep-time re-wilding and resilience, Muñoz shapes the future prime flower (if not already) to be tentacular, centrifugal, and anarchist.

Born and raised in Chicago and currently splitting her time between Chicago and Madrid, Muñoz's practice is a reflection of the concerns of the Chicago artist—the concern on how to authenticate and alchemize the document with the spirit (or vice versa). Raised in Little Village, one of Chicago’s largest neighborhoods for Mexican and Mexican-American culture, Muñoz political consciousness stems from shared national legacies of urban city life and her spiritual values come from the myths her family held on to post-migration to the city. Recognized by Newcity Magazine as a Chicago Breakout Artist in 2023, her work has been acquired by Chicago institutions like the Depaul Art Museum and the National Museum of Mexican Art. She has exhibited in New York, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and Madrid in multiple contexts. One noteworthy circumstance is in “the role of the ‘witch’ or medium in contemporary art” for the exhibition Boil, Toil, & Trouble, where she exhibited quite appropriately in front of a work by Ana Mendieta, with one of Mendieta’s Siluetas.

“We were never perfect,” proclaims Harjo’s poem, surrendering to the fact that there is no end nor beginning to equilibrium. Harjo uses desire as her tool to slow down the spin; Muñoz uses grief, violence, and rage to initiate a balance. Botánica Apokalítica captures Muñoz in moving and transitional work. A flower, a painting, a story—Muñoz’s post-fire technologies are reminders that humans and their relationships are nothing but passing matter in earth’s reach to balance itself.