Encanto Still Has Charm, Despite Generic Representation of Colombia

In 1941, Dumbo, the 4th animated movie by Walt Disney Productions, was released to moderate commercial success. That same year, after animators from the studio went on strike and unionized, Walter Elias Disney would travel to South America on a U.S. State Department sponsored “goodwill” tour to create an animated movie set in Latin America. (That movie would become Saludos Amigos). During that trip, he went to Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Perú.

But not Colombia.

Now, for their 60th animated movie, Walt Disney Productions travels to Colombia. Encanto centers on a magical family—the Madrigals—who live in the mountains and possess special powers.

So far Encanto has achieved great commercial success, topping the Thanksgiving weekend box office. It is now available to stream on Disney+ in the U.S.

Considering that the U.S. box office’s biggest moviegoers are Latinx folks, a movie that reflects one of their nationalities and cultural origins is a welcome decision that resonated with me. I am Colombian-American. Born and raised in Bogotá, I moved with my family to the U.S. at age 18. After learning that the movie was set in Colombia, I was looking forward to watching.

So I went to watch Encanto. I also talked to some other Colombian and Colombian-American people about the movie before and after watching to hear their thoughts.

An Idealized Place

In terms of setting, the creators decided to create a town that could encompass all of Colombia in a locus amœnus. Unlike Colombian Nobel-laureate Gabriel García Márquez’s fictional town Macondo, which is supposedly based on the author’s childhood hometown, Encanto cherry-picks certain geographies and elements of Colombia to create a fictional village.

Juan Antonio Sanmiguel, a childhood friend, said that to see the colorful, biodiverse, and cultural side of Colombia depicted in a beautiful setting in an animated movie was thrilling. Especially since the non-violent sides of Colombia have not been represented in popular entertainment like Netflix’s Narcos, and other narconovelas like Escobar: El Patrón del Mal. The movie depicts the hometown of the Madrigal family as a rural town that incorporates the Valle del Cocora and Caño Cristales. In reality, these places happen to be more than 850 km away from each other. Sanmiguel said that to expect an animated movie to summarize and represent all Colombian multiculturality would not be fair. That’s why focusing on one single place would have been the more accurate choice in my opinion. By creating a fictional town that combines locations and elements so distant cheapens what the places are and what they represent. A very specific and idealized topos that generalizes how viewers see Colombia can be detrimental. Whenever travelers go to Colombia wanting to go to the places the movie depicted, they will be surprised to find that they might not be able to go to the same places the movie depicted as easily as it made it look, and will also get to see that Medellín, Bogotá, and other city centers that are more urban and less rural look less like the Colombia of Encanto.

The Social Construct of Race

There was, however, the Colombian cultural trust of Colombians who were invited to be a part of the movie’s production. Some of its members included Juan Rendón, Natalie Osma, Felipe Zapata, Alejandra Espinosa, Martín and Stefano Anzellini, to name a few. Another member, Edna Liliana Valencia, an Afro-Colombian journalist, was consulted in the movie’s representation of Afro-Colombians. But instead of being invited in, Colombians should have been leading the charge.

The plot includes a mestizo character played by John Leguizamo named Bruno, who is disowned from the family because of his visions. Marcela Rodriguez-Campo, a Colombian Ph.D. with a focus in cultural studies, reminded me that people of Afro-Colombian descent, or even those who are less “white-passing” are in reality the ones disowned because of race in Colombia.

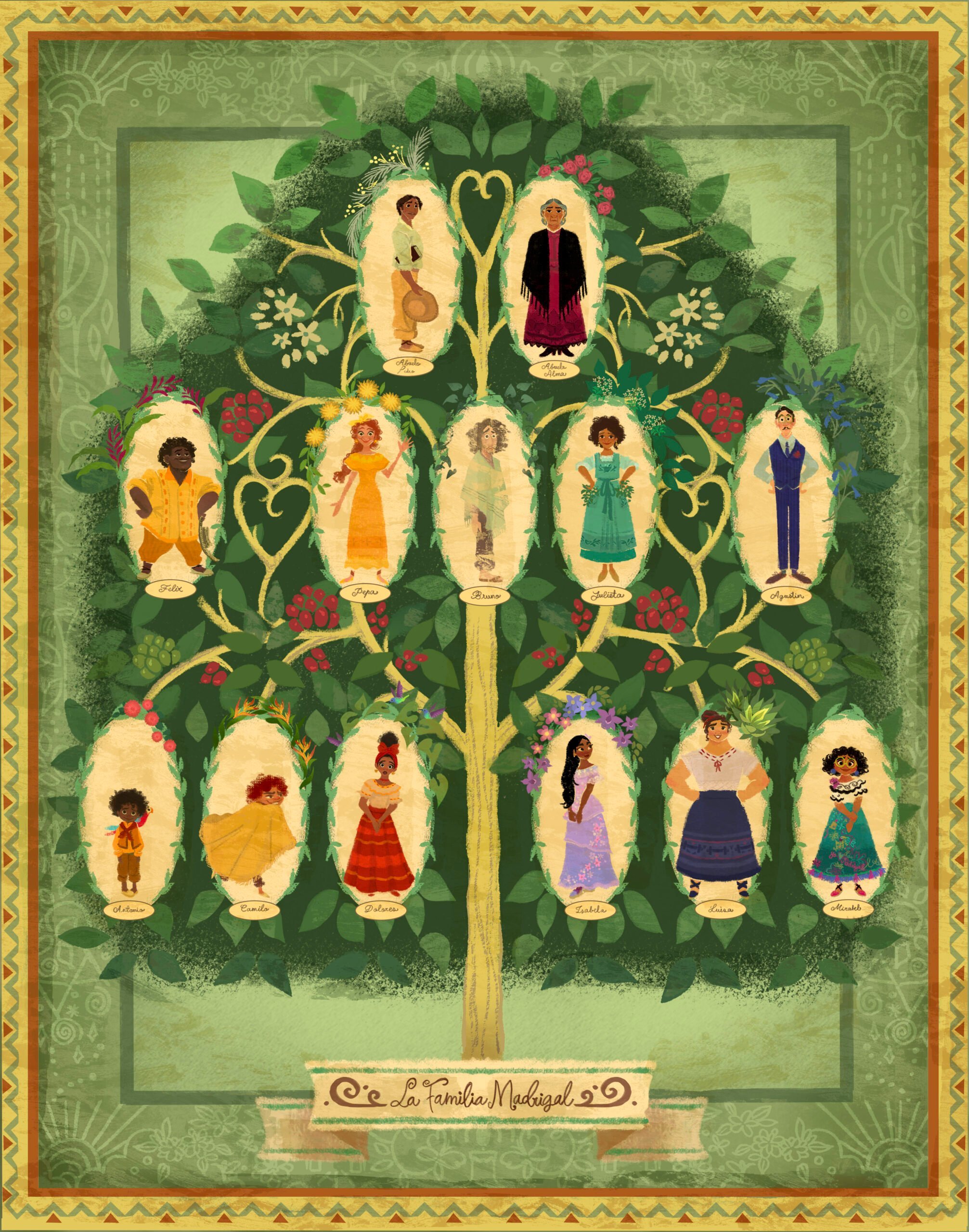

You see a family whose members look very different from one another, but somehow live harmoniously, without having to discuss what race does to each of them, as if this were the case in reality. Maribel doesn’t look like her grandma. Isabela is not similar to her sister Luisa. This is the danger of a generalized and beautiful metanarrative. A family like that? Not even in Cien años de soledad. Thus, Encanto’s representation of Colombia is projected from a U.S. perspective.

At first I thought that the family’s diversity was an issue because it is a highly unlikely scenario. The filmmakers depicted an ideal and not a reality. But as I watched the movie and talked to others about it, I saw it as an ideal to strive for. Perhaps this could be the future of a family from Colombia, which along with its social class system, also deals with its messy mestizaje?

Race is an essential point, Rodriguez-Campo told me. After watching Encanto, the movie got her in her feelings all weekend for various reasons. Although it was beautiful and featured a diverse cast, she said she wished the Afro-Colombian characters were more nuanced. I agreed. It was not just a matter of including the characters and representing them on-screen visually, but giving them depth in their characterization. They were relegated to being secondary and tertiary supporting characters.

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s artistry and work deserve the praise they have garnered. There is a danger, however, in his designation as the go-to Latinx creator for all things Latinx. After the reception of In The Heights and the valid criticisms regarding Afro-latinidad, there are more lessons to be learned. Miranda led the charge for the movie’s soundtrack and also wrote part of the story. But Rodriguez-Campo told me she was disappointed in Miranda’s selection of more popular, white Colombian singers. It might have been more interesting, for example, to have Carlos Vives—who is featured in the main song of the film—curate something akin to Kendrick Lamar’s Black Panther soundtrack. Even then, Rodriguez-Campo agreed that selecting a non-white, mestiza protagonist, Mirabel, as the main character, was an important choice. With an inspirational non-white character comes wariness however, that a character will become emblematic of an entire culture, as has happened with Moana and Coco, which will surely be visible next Halloween.

Attention to Detail

Sanmiguel expected an animated movie version of Andrés Carne de Res, the famous restaurant just outside of Bogotá known for its kitsch and Colombian-themed tchotchkes. We both were surprised by Encanto’s attention to detail.

A kid drinking tinto, yellow butterflies, chigüiros, arepas con queso, white rice in ajiaco, a tiple, and a guayabera—these are some of the details that will delight knowledgeable viewers. The cultural objects and Colombian references were probably the strongest and most accurate type of representation found in the film. To see paraphernalia that could be qualified as Colombian was promising even in the trailer. And in this sense, the movie delivered.

The cultural representation was also reflected in the nuanced language the characters used. One example that made me jump from my seat was a Colombian blink and you’ll miss it reference present in a double-entendre. Agustín, Mirabel’s dad voiced by Wilmer Valderrama, says the word “miércoles.” In this case it does not mean Wednesday, but rather, references what Colombians do to circumvent cranky people who cannot hear curse words and still mean “mierda,” or shit. The delivery of the word, even in the Spanglish of the movie, makes you feel the tone and meaning of the colloquial circumvention even if you don’t know what “miércoles” means.

Consultants and Crew

In terms of directing, producing, music, and writing teams, the movie’s team included Byron Howard, Charise Castro Smith, Jared Bush, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Germaine Franco, and Yvette Merino. The first four of this group were accompanied by Lin-Manuel’s father, Luis Miranda, on a 2018 research trip to Colombia. The fruits of that investigation are visible.

But if you were to look closely at this team, only Castro Smith, Franco, Merino and Miranda are Latinx. In terms of direction, the only Latinx co-director was Castro Smith. But none of them are Colombian or Colombian-American. This was a red flag for me after watching the trailers and learning more about the movie. In terms of crew, they could have hired Colombian or Colombian-American directors—like one of its actors, John Leguizamo, who is also a director—or Danielle Calle, Claudia Fischer, Samir Oliveros, as writers or co-directors. They could have even brought in Colombian animators like Pixar’s Luis Uribe to co-direct the film or be in charge of the story. Bringing in another Colombian animator as one of the co-directors could have offered authentic perspectives for creative decisions. It has happened before, like with Pixar’s Coco, because of a connection to Mexican culture. That this did not happen is not unprecedented. But as none of these things happened, it was a missed opportunity for Colombian animators and directors. One is left to wonder what a Colombian filmmaker would have done differently if given the chance.

The Armed Conflict, Displacement, and Intergenerational Trauma

Encanto’s incorporation of the ineffable intergenerational traumas that stem from the Colombian armed conflict was important. This was the conflict that took the life of the Madrigal family’s grandfather at the beginning of the movie, and it was an emotionally successful and realistic gut punch.

Another Colombian source I interviewed, Diana Ramírez, a Ph.D student at Purdue, echoed the importance of that opening sequence. “I think the initial scenes changed my perspective of the movie almost completely,” she said. “Bringing in the displacement of communities makes it real and something that though is a sad part of our history, helps to bring context. Finally, it shows resilience and the values that Colombian communities seek.”

From trauma and violence, came a gift in the form of a charming magic candle for the Madrigals. But these gifts are hanging over the conflict at hand. Encanto explored this nuance. It addressed the forced displacement of peoples in Colombia, the intergenerational trauma of it all, and the undeniable need to talk about memory and reconciliation after the FARC peace accords. This detail was significant. Especially given that as of recently, the FARC is no longer designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department.

It was harrowing and beautiful to see how the unspeakable manifests in a movie without an external enemy or villain. In this animated movie about a family, its enemy lived within: the horrors of armed conflict and the silences left by violence. And toxicity, even in a loving family, was the reason behind the house’s crumbling foundations. Seeing these themes as a young person will certainly leave an impression and bestow an important lesson.

Encanto and its Charm

Disney needed to create a hit with Encanto. And they succeeded.

Although Encanto wasn’t written, produced, or directed by any Colombians or Colombian-Americans, let’s hope that their next animated or live-action venture values the authenticity behind the creative decision-makers, including its setting and the identities being represented. But with Disney’s 63rd animated movie already announced—titled Suerte—and set in Puerto Rico, which also has Miranda and Castro-Smith attached to be a part of the creative team, it begs the question if Lin-Manuel Miranda will settle for non-Boricuas in significant roles when adapting his own cultural background. I look forward to seeing what they do with this one too.

For now, I will cherish and celebrate the many aspects of Colombia I saw in Encanto, including all of the issues that Disney still needs to acknowledge and work through in their next projects.

Camilo Garzón (b. 1993, Bogotá, Colombia) is a Colombian-American writer, multimedia producer, journalist, editor, interdisciplinary artist, and award-winning poet based in the San Francisco Bay Area. His work has been featured in—or is forthcoming in—the National Geographic Society, NPR, AGU’s Eos, SFMOMA’s Mission Murals Project, KQED’s Rightnowish, America’s Test Kitchen’s Proof, Rest of World, Pizza Shark’s Promised Land, on-off.site, Orlando Sentinel, Brushing Art and Literary Journal, The Creative Independent, NYU Latinx Project’s Intervenxions, among others. He graduated from Rollins College with Bachelor of Arts degrees in Philosophy and Religious Studies, cum laude. He recently won one of the inaugural San Francisco Foundation/Nomadic Press Literary Awards for poetry.