La Treintena 2022: 30+ Books of Latinx Poetry

The past twelve months have witnessed a continued flourishing of Latina/o/x poetry but also an often lackluster critical reception for even some of the most highly visible books. It was a noteworthy year for Nuyorican poetry in particular: witness Willie Perdomo’s appointment as New York State Poet and Martín Espada winning of the National Book Award, for which another Nuyorican poet, Andrés Cerpa, was longlisted. (Both Espada and Cerpa’s books were included in last year’s La Treintena.) Meanwhile, younger queer and trans poets continue to produce some of the most innovative and resonant work, while U.S. Central American poets keep challenging Latina/o/x geographies (a few Central American books are included here and others are forthcoming). In recent weeks, I was thrilled to read and spotlight new and engaging work by iconic figures in Latina poetry such as Lorna Dee Cervantes, Ana Castillo, and Magdalena Gómez, and I look forward to the fall publication of Sandra Cisneros’s Woman Without Shame, her first new book of poetry in nearly three decades. I would like to think that the conceptual and formal range and ambition of the books featured here shows how expansive and thriving our poetries are right now and why they deserve much more attention. Given the limited critical reception, no doubt exacerbated by the pandemic, I have expanded the number of books from 30 to 32 (31 books of poetry plus a poet’s memoir), and I have included microreviews for 23 of those instead of the usual ten. Of course, many more worthwhile poetry books have been published or are soon to be, so I hope you will consider this as a point of departure for you own investigations, and that you will read with the same sense of adventure and possibility that animates so much of this poetry.

antes que isla es volcán / before island is volcano. By Raquel Salas Rivera. Beacon Press.

Here, we witness the oceanic distillation of Salas Rivera’s brilliantly incendiary poetics. Now, the former Philadelphia poet laureate is writing from Puerto Rico, from and to an archipelagic island-ness through spare, shimmering poems from the perspective of a Boricua Caliban: we read his “sycorax, coquíes, cucubanos, and fireflies” and then we turn the book over and upside down and find “luciérnagas” lighting our way. Austerity and extinction are everywhere here, but so is revolution and the uneasily embodied plenitude of a writing that is always queering and transing, quietly erupting into concrete poetry or handwriting, or simply being and making room for us who “know the world hasn’t ended yet” (from “deconstruction of a home”) in the radical refusal to translate. Don’t miss the sequence of poems all titled “la independencia (de puerto rico)” / ”the independence (of puerto rico),” probably the most powerful stretch of poetry I have read this year and one for the future anthologies of a canon-less Caribbean.

April on Olympia. By Lorna Dee Cervantes. Marsh Hawk Press.

Chicana/o/x poetics has always had a strong ecopoetic dimension and Cervantes’s foundational work has been crucial to articulating a Chicana history from, through, and toward land. Here, and just when we need it most, she takes us “back / to the grandmother land. All this Earth, / a gift, a homecoming; revival of the species.” Beyond celebrations of nature, this is poetry attuned to the ancestors (there are several elegies here, including a memorable one for Francisco X. Alarcón), and to how “the thin / grease of the living and / dying fills us with mercy.” Don’t miss “On Feinberg’s Theory of Physics,” a gorgeously eccentric embodied epistemology that confronts our global deracinations: “I walk about this de- / localization, circling aimlessly around some / nowhere no one’s planet loneliness. I give / into it.”

Cipota under the Moon. By Claudia Castro Luna. Tía Chucha Press.

El Salvador-born, Seattle-based, former Washington State Poet Laureate Castro Luna writes powerfully about the 1980s civil war and immigrant histories. Still, what is most memorable here is the elegant and shifting poetics of self-figuration, evident in everything from the echoes of song to the title’s play with the last name “Luna.” Even in poems about political terror, Castro Luna finds a way to both embody and counter the violence, as when two girls walk by armed soldiers and the girls are “guillotining chatter and laughter.” Don’t miss Castro Luna’s experiments with the prose poem, as their linguistic accretion carries the weight of struggle.

Count. By Valerie Martínez. University of Arizona Press.

Here, Martínez—former poet laureate of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and author of the Arizona Book Award-winning Each and Her (2010), among other books—writes us beyond an ecopoetics of nature “out there” and toward a poetics that counts the seconds and the losses in a burning planet. She meditates on both the beautiful solace of water (“Let us go now, you and I, to the water—to the girl / who stands alone at the sea)” and its contentious embodied geographies, from Miami’s Biscayne Bay to the Rio Grande. Notably, the book has no page numbers and is composed of 43 numbered sections (mostly couplets) whose autoethnographic flow seeks to engage indigenous knowledges and to counter how our global rootlessness facilitates ecocide. As the notes at the end make clear, the book is in conversation with the work of an international range of installation artists and builds on Martínez’s collaborative 2012 “ecowalk of the length of the endangered Santa Fe River.” Poetic epiphany gives way here to an observational narrative that can still make room for the kinds of rhetorical questions that animate poetry: “Are we singing? Are we dancing? / Are we waving frantically in distress?”

Danzirly. By Gloria Muñoz. University of Arizona Press.

Winner of the Ambroggio Prize of the Academy of American Poets, this book by Colombian American poet Muñoz shuttles back and forth between English and Spanish, the sleek movement of its stanzas echoing the poems’ diasporic sensibility. Even as Muñoz riffs on how our phone cameras connect us as we struggle to reconcile “the Age of Information / and the Age of Experience,” the poems’ linguistic migrations are mindful of materiality: “We’ll also leave you / a clusterfuck of concrete / and other impenetrable matter” (“También te dejaremos / un mierdero de concreto / y otra materia impenetrable”). A shoutout to the poem “The Veteran Parked in His Wheelchair at the Intersection with His Golden Retriever at His Feet Holds a Sign that Says: I’ll Take Anything,” which reembodies the immigrant poem from a complex Colombian American perspective, at the limits of family and nation.

Desgraciado: The Collected Letters. By Angel Dominguez. Nightboat Books.

In a fascinating departure from their previous book RoseSunWater, which I discussed in last year’s Treintena, Dominguez, a Los Angeles poet of Yucatec Maya descent, here radically reimagines the epistolary form through letters addressed to Diego de Landa, a 16th-century Spanish bishop infamous for destroying Mayan codices. While the concept sounds somewhat similar to the late, aforementioned gay Chicano poet Francisco X. Alarcón’s classic Snake Poems: An Aztec Invocation (1992), tonally it seems to me closer to a decolonial analogue to Jack Spicer’s queer After Lorca (1957), since, as Raquel Salas Rivera writes in his brilliant introduction, Dominguez invokes Spanish colonizer de Landa as “a dead and unrequited lover” yet “unlike Spicer, Dominguez seems to be sustaining the relationship only in order to wound back.” These are performative love letters to “Dear Diego,” whether signing off with a variant of “Love” or “Kisses” or “xoxo” or the eerie “Always yrs.,” and even when signed, by turns, “A,” “AD,” “un angel,” “Tu Amor,” “Tu Sangre,” “-Tu angelitx,” or “AD(og).” What emerges is a poetics of queer decolonial intimacies that works as a speculation on the wounds and silences of mestizaje. As Salas Rivera argues, Dominguez goes beyond critiquing de Landa’s disgracefulness and toward a queer poetics of “our shared disgrace,” where our subjectivity is shaped by loss and where poetry’s power is “bringing genocide into the bedroom, and the bedroom into the colonizer’s history.” Later in the book, the letters morph, sometimes all uppercase and others into concrete poetry and superimposed text. Still, as engaging as Dominguez’s radical écriture is, some of the most gripping moments in Desgraciado are those of silent reckoning, as on page 73, which reads in its entirety:

“Diego,

I am only every trying to remember.”

Golden Ax. By Rio Cortez. Penguin Books.

Utah-born and raised African American and Afro-Nuyorican poet Cortez’s debut collection offers a fascinating and searingly written exploration of her family’s “Afropioneer” history in the western United States. Combining research, narrative lyric, and poetic prose as a mode of counter-memory, Cortez helps us think beyond hegemonic histories and archives. Elsewhere in the book, Cortez evokes the shadows of New York as a site of fraught ancestry, and she reflects on necropolitical histories and the place of the African diaspora across other racialized, gendered, and classed geographies, including Cuba.

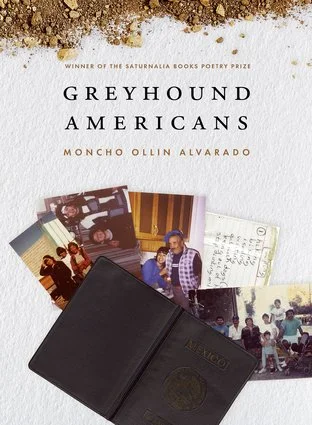

Greyhound Americans. By Moncho Ollin Alvarado. Saturnalia Books.

We can read this first book as a sonic-graphic poetics of embodied trans figuration (to echo Francisco Galarte), as exemplified by the opening poem “Self-Portrait with La Sonora Dinamita Playing in the Background,” with its trilingual English-Spanish-Nahuatl poetics of tonacayo/flesh. Alvarado, a self-described “sister-in-residence in air, a Cihuayollotl trans woman, Xicanx poet, translator, visual artist, and educator,” fleshes out her pages with family portraits and searing, class-conscious lyrics such as “Is My Life Really Worth 12 Dollars an Hour?” while working in an expanded field than includes oral/aural (corrido, musical score, etc.) and formal experiments such as the ABC’s of “Abecedarian Payday Inside the Projects” and the (anti-)list poem “A List for Every Time My Depression Tries to Obituary Me.” The long, dazzling “Border Walls” uses bursts of short, willfully broken, largely punctuation-less translingual text arranged in three columns to imagine a liminal space of possibility where “veillance cameras” suddenly “de vigilan.” Against such a backdrop, the spare, plain language of the closing title section’s migrant family narrative is like a kick in the gut but also a rush of blood to the heart and song of defiant queer/indigenous memory: “I shovel the soil with both hands / hold it to the sky / streams from my fingers / I hear my name.”

Living on Islands Not Found on Maps. By Luivette Resto. FlowerSong Press.

In her third book of poetry, the Puerto Rico-born, Los Angeles-based, Bronx-raised Resto showcases an expansive poetics, ranging from the elegance of the opening “Yemaya’s Pantoum” to experiments with the villanelle, the prose poem, and the list poem. She is equally clear and fearless whether writing about gun violence (the short, heartbreaking “Breakfast Conversation with My Oldest Son”), pop culture from her youth (an ode to iconic boy band Menudo), the gendered politics of home (“Painted Walls”), or in powerful, fresh poems about love and sexuality. There’s the languid eroticism of “The Moon Like Language,” the epic “My Love Is a Continent” (a shoutout to “las malcriadas, chingonas, cabronas, jefas, y sin vergüenzas”), the raw “Succubus” and “MILF,” and the irrepressible “A Letter to Gus, the Judgmental CVS Clerk,” which has the mic drop power of the best slam pieces. What other poet could rock the title “A Poem for the Cunt on My Couch” this smoothly, or juxtapose “the gentrification of boyhood memories” and “the irony of Paine’s title Common Sense” with a flow that feels both playfully wise and necessary? Don’t miss the anthemic “The Case of My Resting Bitch Face (R.B.F.),” where humor, truth, and fire are poised against “the devolution of language,” as well as the title prose poem’s moving depiction of the beauty and struggle of interlingual urban lives: “We were bilingual neologists, inventing new lands we could carry in our Timbs and bubble coats.”

As I write this in the Bronx, I’m adding Resto’s “A BX Love Letter” to my mental summer poetry playlist.

Madness. By Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué. Nightboat Books.

The subtitle of Madness is The Selected Poems of Luis Montes-Torres (1976-2035), a fictional queer Cuban poet who migrated at age four to Florida as part of the Mariel boatlift of 1980 and grew in Virginia, eventually living in Washington D.C., Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, publishing several books of poetry on the peripheries of mainstream publishing, taking up meditation, and dying of brain cancer. Beyond the invention, what is most memorable here is the way the Montes-Torres persona allows Ojeda-Sagué (who is of Cuban descent, from Miami, and has lived in Philadelphia) to expand upon his earlier books’ eccentric explorations of a queer Latino aesthetic while playfully reimagining a dystopian queer futurity (sorry for tweaking the late, great José Esteban Muñoz). Some Montes-Torres poems are convincingly in the voice (is there one, the author asks?) of something like a recognizably queer (“I connect to the men of American cities”) Cuban American lyric (“In this country, touch has patterned me” in the poem “Mirada”), even reclaiming the derogatory term for an anti-communist Cuban “Gusano” (literally a worm) in the poem of the same name, which ends with a striking: “Split out / From under you to engulf you.” Yet, according to one of the “editors’ notes” Ojeda-Sagué includes, Montes-Torres’s later books, abandon “the lyric short poem in favor of the long poem, embrace rigid and repetitive line forms, and mark a new pessimism” in his work, as it becomes “wordy, weighty, and often cynical.” Still, this later poetry is fascinating precisely because it urges us to imagine a future for poetry amid climate and political dystopia, and Ojeda-Sagué has the talent as a writer to make this poetic pessimism swing, as in the coiled stanza below, whose indented permutations stretch on for pages:

changing color of water

in response to the introduction

of water into the city

an imprecise dictation

of what is hurting in the space

between the finger and the brain

Magnificent Errors. By Sheryl Luna. University of Notre Dame Press.

Since her 2005 debut Pity the Drowned Horses, Luna has excelled at the elegant lyric, yet what stands out here are the interior landscapes that bridge a visionary attention to nature and raw reflections on mental illness, abuse, trauma, and healing. Especially memorable is the use of a fractured yet autobiographically coded “she,” sometimes alongside the first person in pieces like the searing prose poem “The Artist Addressing Violence.” At the end of the book, its many beauties and violences coalesce and soar into a striking crescendo in poems such as “Clouds and Sapling” (sample lines: “Finding the trauma, turning its sharp key, / opens the way for splendor”), “Prayer for this Clay Earth,” (sample line: “Teach us the language of spilling out of ourselves”), and “Mud” (sample line: “the I sits at the periphery of loss”). Luna’s book beautifully expands upon the many intersections between Chicana ecopoetics and disability poetics, while claiming its own lyric territories.

My Book of the Dead. By Ana Castillo. High Road Books.

Any book by Ana Castillo is an event, and as one would expect this one pulls no punches, with titles like “How to Tell You Are Living under Fascism (A Basic Primer in Progress),” a poem that someone needed to write and that earns its seemingly performative hyperbole with clear-headed bravado (first line: “Protests are called riots”). As befits its title, the book includes several knotty elegies, including one for queer African American poet Akilah Oliver and another for Francisco X. Alarcón (third time’s a charm!), the latter one of several poems in Spanish included in the book with English translations by Castillo and others. A standout is “These Times,” a syncretic manifesto of defiance, wisdom, and care in the context of aging and our dystopian moment. Also echoing in me is “On the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Black Panther Party,” a love letter from an indigenous Chicago that morphs into a heartbreaking, raw, yet necessary litany of struggles and a reflection on the precariousness of our shared political dreams.

MI’JA. By Magdalena Gómez. Heliotrope Books.

Gómez has long been a bridge between the foundational Nuyorican poets of the 1960s and 1970s and younger generations of poets and performers. MI’JA is another kind of bridge: what Gómez characterizes as a “memoir noir” that combines poems and dream records with vivid yet often raw and painful prose remembrances of growing up in the Bronx during a time of transition with parents steeped in old ways, and of watching the borough transform and fray without losing its sense of struggle or its defiant humor, just as Gómez never has. I was especially impressed by the book’s sensitive and nuanced take on queerness in the mid-century Puerto Rican South Bronx (fleshed out by poetic evocations of Federico García Lorca, a longstanding inspiration for Gómez), and by Gómez’s ability to depict her often strained relationship with her mother with both unflinching candor and a sense of human complexity. Don’t miss the numerous creative and syncopated renderings and remixings of the Boricua Spanglish of the time, a treasure trove of New York Puerto Rican history reanimated by the ear and flow only a poet and performer like Gómez could bring.

open pit. By José Antonio Villarán. Counterpath Press.

California-based Peruvian poet Villarán’s processual approach here is rigorously anti-poetic and conceptually layered in its critiques of extractivism (rooted in and around the Peruvian town/mine/ghost town of Morococha), yet moving in its evocation of personal and family histories under constant threat of erasure, an erasure the text performs through its combinations of lists of everything from minerals to the computer materials built from them, and from Peruvian presidents to the indigenous peoples extractivist histories erase. Especially powerful is Villarán’s writing to his son as it indexes the very planetary futures the text’s detritus risks drowning out: “i live in san diego, california, and write about extractivism on a computer made primarily from minerals. you’ll be one-year old next week.” Later we get “y no habían respuestas para darles a nuestros hijos” followed by the open-ended questions “what is copper? / what is gold? / what is mercury?,” which then permutate, echoing the same computers the text indicts, as if confronting us with our own reading as an extractivist act. Don’t miss the last 50 pages or so, where the speaker addresses his son more directly and the lists give way to period-less digital oraciones (sentences, prayers) for a lost world the son will never know: “this urgency, to remember the river’s murmuring” (“A Question of Loss”).

plagios. By om ulloa. kýrne.

This book of “plagiarisms” remixes Cuban greats such as Ernesto and Ernestina Lecuona, Beny Moré, Severo Sarduy, Lorenzo García Vega, Reinaldo Arenas, José Lezama Lima, José Martí, and Virgilio Piñera along with hemispheric and global shards of poetic modernities and modernisms (Miguel Hernández, Samuel Beckett, Wallace Stevens, Pablo Neruda, Shakespeare, Sor Juana, Elizabeth Bishop, Eliot, Borges, Dostoyevsky, W.C. Williams, Oliverio Girondo, etc.) into translingual post-Spanglish poems with titles like “atoMarPorcuLO” and the all-uppercase Emily Dickinson shoutout “fame iS a has-bEEn.” The Chicago-based Ulloa, who was born in Matanzas, Cuba and has lived in the US since she was a teenager, turns these strains and strands into an elusive yet dazzling linguistic performance that (as Kristin Dykstra notes in her introduction) spans everything from Afro-Cuban Abakúa and Trío Matamoros to Tristan Tzara and Dada. Don’t miss the trip-hoppings of Dante via El General’s “Tu pum pum” and The Trampps’ “Disco Inferno,” as well as the fabulous (I wish I would have done it!) “howlin’HavanaeNuevayOrk,” which hooks up Ginsberg’s “Howl” and Lorca’s Poeta en Nueva York in a queer reverie on the soul amid the urban solitude: “a piñazo limpio y plumazo sucio banging on the floor and on each other.”

Quanundrum [i will be your many angled thing]. By Edwin Torres. Roof Books.

This book feels like the summation of the verbivocovisual ecoambient poetics Torres has been refining since 2007’s The PoPedology of an Ambient Language. A lot has changed in these 15 years, and any such poetics is bound to be more dire these days. To be sure, there is a tossing and turning of identities here that feels less like the Nuyo-Futurist utopianism of Torres’s early work and more like a disavowal of facile identity politics, including nationalisms. Torres doesn’t want us “HUNG UP ON A NATION” and navigating “INTERNET POLLUTION,” and if this book has a politics it seems closer to the unknown, the impossibly celestial or the “galactic ethnic” emphasized by Kristin Dykstra in her excellent review of the book. For Dykstra, the “AVANT GARDE’O’RICAN” that Torres proliferates is its own kind of (kinda?) politics where: “the creation of poetry constitutes a type of immaterial labor in the contemporary capitalist economy” and where we are asked to engage “politics and poetics as deeply volatile states, bundles of tension, which our many personhoods negotiate.” What I would add to Dykstra’s smart take is that all this dovetails with Torres’s recent move toward a mode of what we might call unknowable identity politics (the title as portmanteau of quandary and conundrum, but also all the many angles in the subtitle as a sort of empty [in the Zen sense] intersectional politics). This also happens to be an okay self-care response to climate collapse and such, and in that sense the galactic here feels less about escapism than about our eternal becoming, like the Pedro Pietri of El Spirit Republic (Torres has long been probably the best reader of Pietri as experimental poet/performer in all the Nuyorican tradition). The title is also perhaps about the quantum drum that beats within and through us, one the many ellipses throughout this book echo and amplify. Fatherhood cuts through the book, and ecological future is nested uneasily within in a meditation on the “animal-ment of us,” not for better or for worse but just as is, as we are. Forget the future of the species, Torres seems to be saying, use your ellipses, feel your way through elliptical language and feel the energy of Earth’s ellipse.

Rotura. By José Ángel Araguz. Black Lawrence Press.

Expanding upon how Araguz’s 2017 book Small Fires explored the “crucible of Mexican-American identity,” this book invites us to read the titular gap/tear/gash as a metaphor for personal and social identity in a time of broken relationships, families, institutions, and political imaginaries. At the same time, the gorgeous, Czeslaw Milosz-inspired long poem “Certain Rivers,” works as a contemporary disruption of the modernist ruin poem, from Eliot’s The Waste Land to Octavio Paz and beyond. When Araguz writes “When a river’s crossed, / how many families hold their breath?,” we can’t help but think of the Rio Grande, but the poem opens up at the end into another kind of rupture, as Juan Felipe Herrera notes in his back-cover blurb, one animated by “shimmers of truth, family, longings and stark existence.” To quote Araguz:

“to grieve that one cannot grieve,

no hay tiempo,

tus hermanos, esta casa

nunca está limpia”

Shoreditch. By Miguel Murphy. Barrow Street Press.

Murphy is to my mind a leading queer Chicano/Latino poet, but he remains underappreciated, perhaps because his work is often minimalist, dark, feverish. Shoreditch might be the most potent articulation yet of his elusively allusive poetics, with its extended riffs on Caravaggio, Lorca, and Pasolini, and a poetic prose worthy of Jean Genet (or maybe John Rechy, given its shadows of Los Angeles). The book wears its “sadistic” erotics on its sleeve quite performatively (Shoreditch is a district in London famous as a hub for Elizabethan theater) but it also sensitively reflects on the body’s devastation and decay.

Stepmotherland. By Darrel Alejandro Holnes. University of Notre Dame Press.

I discussed queer Afro-Panamanian Holnes’s Migrant Psalms last year and several of the poems in that chapbook are included in this debut full-length poetry book, which was chosen by John Murillo for the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize and recently reviewed in Intervenxions. Suffice it to say that “Af.ri.can-A.mer.i.can.ize” is an essential poem about Afro-Latinidad in relation to the category of African American. Suffice it to say that you should check out the closing “Black Parade,” with its punning insight into the resonances between the word “marica (the f-word) and “America.” Suffice it to say that “Rihanna & Child” sharply redeploys quatrains to give us a defiant take on the motherhood poem (“I was raised by her kind”). Suffice it to say, you shouldn’t miss how Holnes writes about the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama, using his skills as a playwright to dramatize intimacies beyond the geopolitical (“I see my own blood for the very first time”).

To Love an Island. By Ana Portnoy Brimmer. YesYes Books.

The daughter of Mexican-Jewish immigrants, born in New York but was raised and living in Puerto Rico, Portnoy Brimmer opens her debut poetry collection with a poem about the mistaken belief that “strawberries couldn’t grow in Puerto Rico.” The poem ends with the lines “I’d always been told freedom would never come / for Puerto Rico. We didn’t have the climate.” followed by couplet in which a farmer in Puerto Rico points out to the speaker some strawberries growing wild. It is a fitting opening for a book that pays deep, embodied attention to Puerto Rican landscapes (“I ask you to forgive me / for the earth tumbling out of my mouth”) captured through lines that coil like vines or grow wild like grass across the page, often with slashes in the middle like little machetes. This skillful play with lineation also does the work of evoking everything from sargassum (in the poem of the same name) to a pelican in flight to Puerto Rico’s difficult rebirth after Hurricane María, whose dead echo throughout the first part of the book. Later, in poems like the Aracelis Girmay-inspired “Ode to my studio apartment in Forest Hill, Newark” or the upstate New York poems that follow it, lineation marks geographic and affective distances. Don’t miss the many poems referencing Puerto Rico’s summer of 2019 (aka Telegramgate or #RickyRenuncia), including the unforgettable “Ode to the cacerola combativa.” Other standouts are the (de)colonial somatics poem “GERD,” the shoal poetics of “Rhizomatic,” the syncopated “Island ghazal” (sample line: “colonial debt, fuck the debt, no longer afraid of your threat—prophet”), the mutual aid/autogestión manifesto “Let it tremble,” the visionary Caribbean anthem that concludes the book (“Smallness”), and the title poem, which evokes the hurricane’s aftermath with a harrowing “sooted brush of mouths / dust down your rivered // throat / to your Superfund / womb.” Lines to linger with:

“But I will know the beauty of living—dying, in the anonymity

of everything and everyone, the rearguard and collective shadow,

with nothing to show for it, but an archipelago, a world, closer to our imagining.”

We Are Owed. By Ariana Brown. Grieveland.

In this debut, a Black Mexican American poet begins by writing from the perspective of her Texas childhood, mourning the death of her African American father in an Air Force collision. From there, the book reflects on being the only Black girl in a largely Mexican school (“There Are Güeros and Then There is Me”), and it juxtaposes poems such as “Negrita” with critical notes or trenchant historical observations on everything from Aztec imperialism and settler colonialism in Texas to the need to find a language beyond Gloria Anzaldúa and mestizaje. As Alán Peláez López argues in their foreword, betrayal and critical speculation become for Brown key strategies toward a new political imagination attuned not to European settler origin stories but to fugitive figures like the legendary rebel maroon leader Gaspar Yanga, who is central to the middle of the book. Brown writes Yanga into the center of this alternative history in poems haunted with a cross-temporal intimacy, against the Mexican Studies “lecture notes” earlier in the book. Don’t miss the anthemic “Don't Know Nobody from Ellis Island,” the intricate constellations of racial (counter-)geographies in the Mexico City poems, and the autobiography-as-manifesto “Introductions.”

What Flies Want. By Emily Perez. University of Iowa Press.

The blurb-writer in me says this book’s lyric imagination defamiliarizes quotidian tales of love, children, marriage, and depression into “the clear hum, the strum and thrum / of energymatter.” In Perez’s poems, as in her namesake Dickinson’s, “the beast is unpredictable” and “detritus is stirred” until truths come out of the woodwork: as taut lines, breathless prose blocks, found poems, anti-epiphanies. Especially noteworthy is its sustained investigation of whiteness in poems such as “Prayer for my White Son” and the ruefully comical “Dear Whiteness.”

Why the Assembly Disbanded. By Roberto Tejada. Fordham University Press.

The latest book by Colombian American poet, art historian, editor, translator, curator, and recent Guggenheim fellow Tejada is perhaps the most forceful poetic assemblage yet of his unparalleled hemispheric critical and creative project. Tejada’s writing builds through accretion and distillation, in conceptual conversation with a range of forms, from the Twitter feed to the photographic works of Connie Samaras or Rubén Ortiz Torres to Amiri Baraka’s insights on racialized geopolitical personhood. Whereas earlier books such as Mirrors for Gold (2006) were more formally rooted in and against the Latin American baroque, Why the Assembly Disbanded mines couplets and tercets for a sedimented self-figuration, and it continues Tejada’s ongoing exploration of the prose poem as a mode of process theory. The concluding “Envío” works as a nod to the hemispheric poetic remittances that cut through Tejada’s work since his days editing the acclaimed journal Mandorla: New Writing from the Americas (for which—full disclosure—I was a contributing editor), but also to Jacques Derrida’s “Envoi” and to a translingual writing that foregrounds language’s slippery materiality, right down to the author’s signature at the end. Don’t miss the gorgeously abstract “Film Noir: Telescope,” a cinematic noir take on Tejada’s native Los Angeles that opens up via Nat King Cole’s version of Consuelo Velázquez’s “Bésame mucho” into a rumination “on the subject of my vanishing.”

—

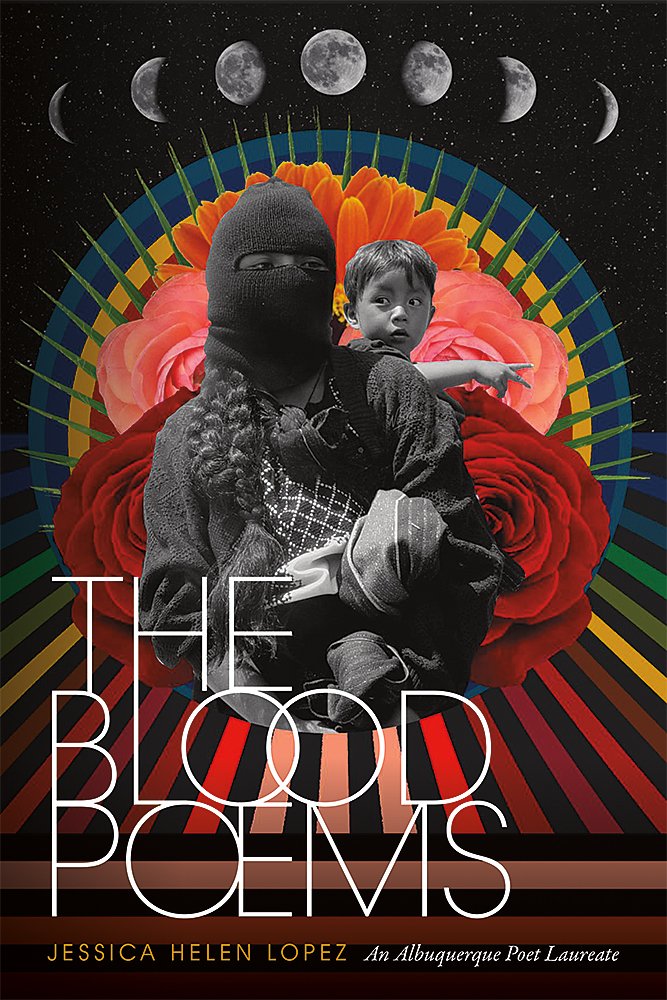

The Blood Poems. By Jessica Helen Lopez. University of New Mexico Press.

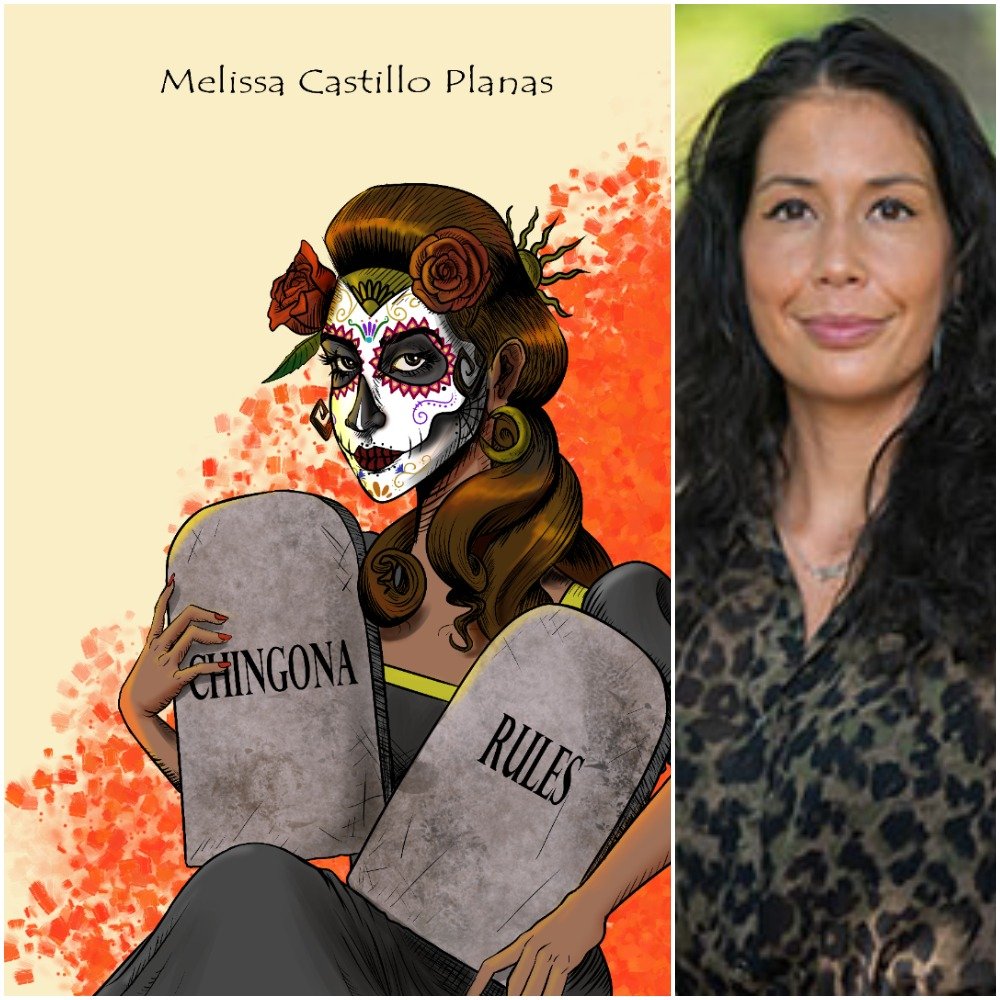

Chingona Rules. By Melissa Castillo Planas. Finishing Line Press.

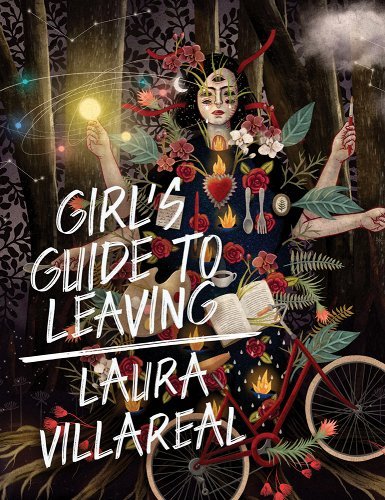

Girl’s Guide to Leaving. By Laura Villareal. University of Wisconsin Press.

Headless John the Baptist Hitchhiking. By C.T. Salazar. Acre Books.

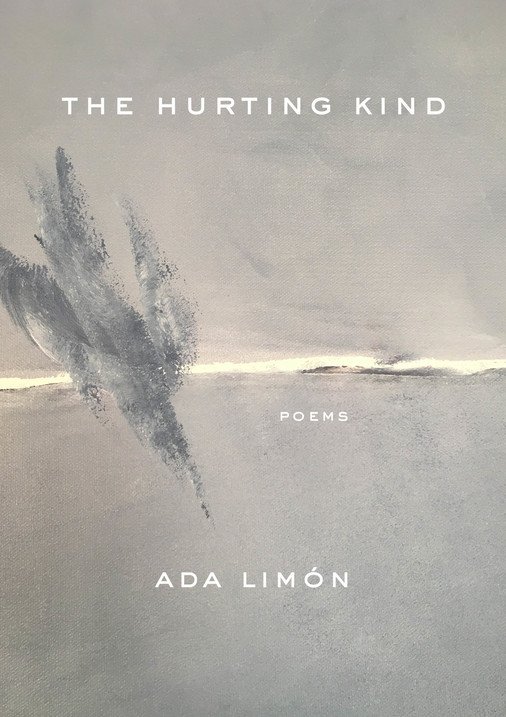

The Hurting Kind. By Ada Limón. Milkweed Editions.

Inheritance: A Visual Poem. By Elizabeth Acevedo. Quill Tree Books.

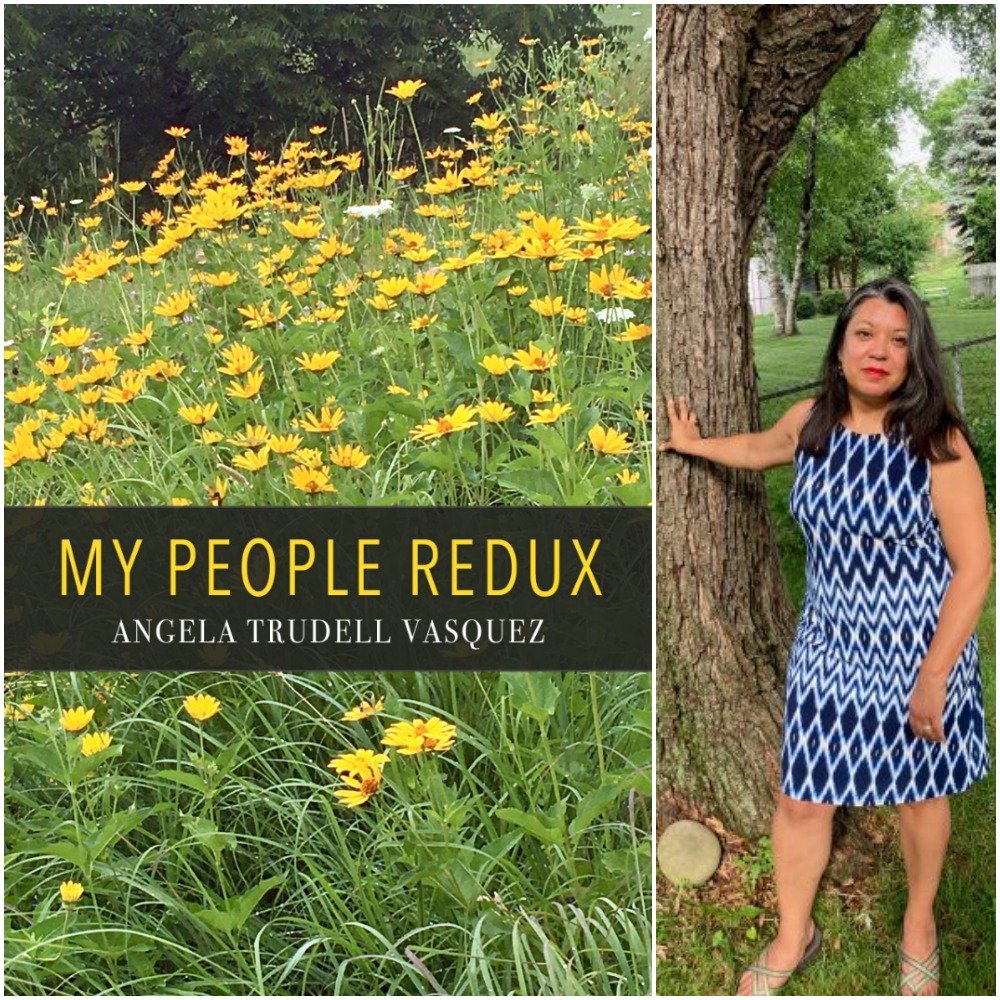

My People Redux. By Angela Trudell Vasquez. Finishing Line Press.

Quotient. By Felicia Zamora. Tinderbox Editions.

Under Capitalism If Your Head Aches They Just Yank Off Your Head. By Ariel Francisco. FlowerSong Press.

Urayoán Noel is an associate professor of English and Spanish and Portuguese at NYU and serves on the Latinx Project Faculty Board. His most recent book of poetry is Transversal (University of Arizona Press).