Lo Que Es Pasado Nunca Vuelve: A Journey Back To Puerto Rico Before Maria

Puerto Rico.

Surrounded by the deep blue and green Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea.

The old, colorful, colonial architecture of El Viejo San Juan,

the warm people saying buen provecho as they pass by you eating.

The savory alcapurrias, bacalaito, mofongo, lechón, platano maduro, arroz con gandules and un café colao calientito.

The salt flats on the west, the rainforest on the east and Jayuya with Taíno petroglyphs in the center.

The Puerto Rico we desire to stay in. The Puerto Rico some of us stay in. The Puerto Rico we leave. But always the Puerto Rico we come back to.

Mi Puerto Rico, nuestro Puerto Rico.

—

Ten months after PROMESA was signed into law,

a month before Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and Puerto Rico declares bankruptcy,

a year and half before the protests of #RickyRenuncia,

two and a half years before the earthquakes and the COVID-19 pandemic,

and almost four years before the electricity system was privatized…

My mom and I returned to Borinquen in August 2017 to backpack the island for a week.

Two diasporic journeys in one—my mom’s return to her childhood barrio after 34 years, and myself, a Nuyorican, returning to visit the island after four years.

Earlier in the summer, I presented Ma with the idea. She left Puerto Rico as a 17-year-old and never got to know the island outside her own barrio and my dad’s hometown, Salinas. Having backpacked the island by myself for a month and a half in my early 20s, I felt a duty to show her more of the place she loves so dearly.

In planning for the trip, my mom expressed an interest in visiting her childhood home in Cataño. It is the only possession her parents left her and her siblings before they passed away when Ma was nine years old. Four decades after migrating to New York, she wanted to know how the place she grew up in was. So in her New York City public housing apartment, we committed to looking for it. She was emocionada.

—

This is our journey in photos through my eyes of always returning to an unpredictable, changing place—where we were immersed in the island’s beauty, as well as its ongoing political and socio-economic issues, which we faced every step of the way.

Santurce

Known as the only neighborhood founded by freed black slaves, began to decline in the 1970s when people moved to the suburbs, similar to neighborhoods of other major cities. Those who couldn’t afford to leave stood, in this case, Dominican immigrants and low-income folks who predominantly lived in large areas of public housing.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, Santurce continued to suffer economically. In an attempt to restore the area, the district focused on trade and tourism, attracting a new wave of restaurants, coffee shops, bars, and clubs. The low rents attracted artists as well.

And in came gentrification.

A decade later, Santurce has become the headquarters of LUMA Energy, the private electricity company that continues to leave thousands of Puerto Ricans without power since mid-2021.

Walking around Santurce…

we experienced a complex place—rich creativity juxtaposed with abandoned homes and empty streets.

We planned to visit Ma’s childhood home the next day. We ate breakfast at La Mallorca and then took la lancha from Old San Juan across the bay to Cataño. With Ma’s slight familiarity of the streets and following Google Maps on an iPhone, we found a world of old recuerdos, disillusionments y alegrías.

We walked around the area but couldn’t quite spot Ma’s childhood home. When we turned a corner, she saw a family friend and as we walked towards her Ma asked, “¿Te recuerdas de mí?” “Sí, mi hija, me recuerdo.” And they talked for a little while about how our family was and how she remained in the barrio after so many years. In conversation, my mom asked about the location of her home. The family friend responded, “Well, it’s there,” pointing to a passageway across from her house where we were standing.

Ma couldn’t spot the house because where once there was un callejón my aunts, uncles, and grandmother walked through every day to get to their home, someone had placed a gate with lock and key.

We asked the family friend if she knew who lived there and a few moments later, a mother with her two sons came walking down the passageway. We immediately approached the gate and explained to the mom who we were and that we wanted to get access to the house in the back. The family friend vouched for us.

The mom begrudgingly let us pass as she followed us down the passageway.

Walking to the end of the callejón, we saw a concrete wall and a fence that blocked any access from that side of the house. We were only able to take pictures from behind the fence.

We asked the mom, the current resident of the white house to the right, who had put up the wall. She responded that the wall was already there before they moved in a few months ago.

We thanked her, left, and walked across the street to the family friend.

The family friend mentioned that a past neighbor of my mom’s lived on the other side of the house. Nos despedimos and walked around the corner. The neighbor, who happened to be outside on her porch, recognized Ma right away. Ma explained the situation while a very loud dog barked in the background. The neighbor explained to us that the house is closed in on all sides and the only way to access it is through someone else’s home. We asked if we could walk through her house. She said that she had very large dogs in the house she couldn’t handle by herself so we would have to return when her husband got home later.

We didn’t get a chance to go back.

A month later, Hurricanes Irma and Maria swept through Borikén. We don’t know if my mom’s childhood home is still there or its condition, but we do know that Cataño was hit hard by sustained winds of up to 155mph. Eighty percent of the working-class housing was destroyed or damaged.

Cataño

Cataño, best known as the home of the Bacardi factory, is the smallest town in Puerto Rico named after the Spanish doctor, Hernando de Cataño, who practiced here in 1569 when the island was under Spanish rule. Similar to Santurce, there has been an attempt of “revitalizing” the barrio covering many of the buildings with art.

A Christopher Columbus statue still stands in the main plaza.

For the rest of the day we explored Old San Juan, walking slowly on the cobblestone streets. We contemplated whether the family still owned the home or if the laws around abandoned property (Article 749 and 762) applied.

Before we left Cataño, we stopped by my mom’s older sister’s house a few minutes away, which she hadn’t visited in about 40 years. We found out that my aunt’s husband’s brother, who was watching the house, had passed away and another family was living there. They claimed the property had been abandoned for a long time and that they now owned it.

Now, walking on the outer edge of Old San Juan, overlooking the sea, we saw La Perla.

La Perla

A slaughterhouse from 1804 to the 1960s, where slaves, homeless, and non-white servants and then farmers, city workers, and even troops have lived. It has become infamous for its reputation of violence and drugs. But on the other hand, La Perla is a beautiful community full of love, creativity, and strength.

Even after the government’s attempts of ousting the residents for many years, developers trying to buy the land, and the U.S. emergency aid nonexistence in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the people remain to live in the resistance and in community.

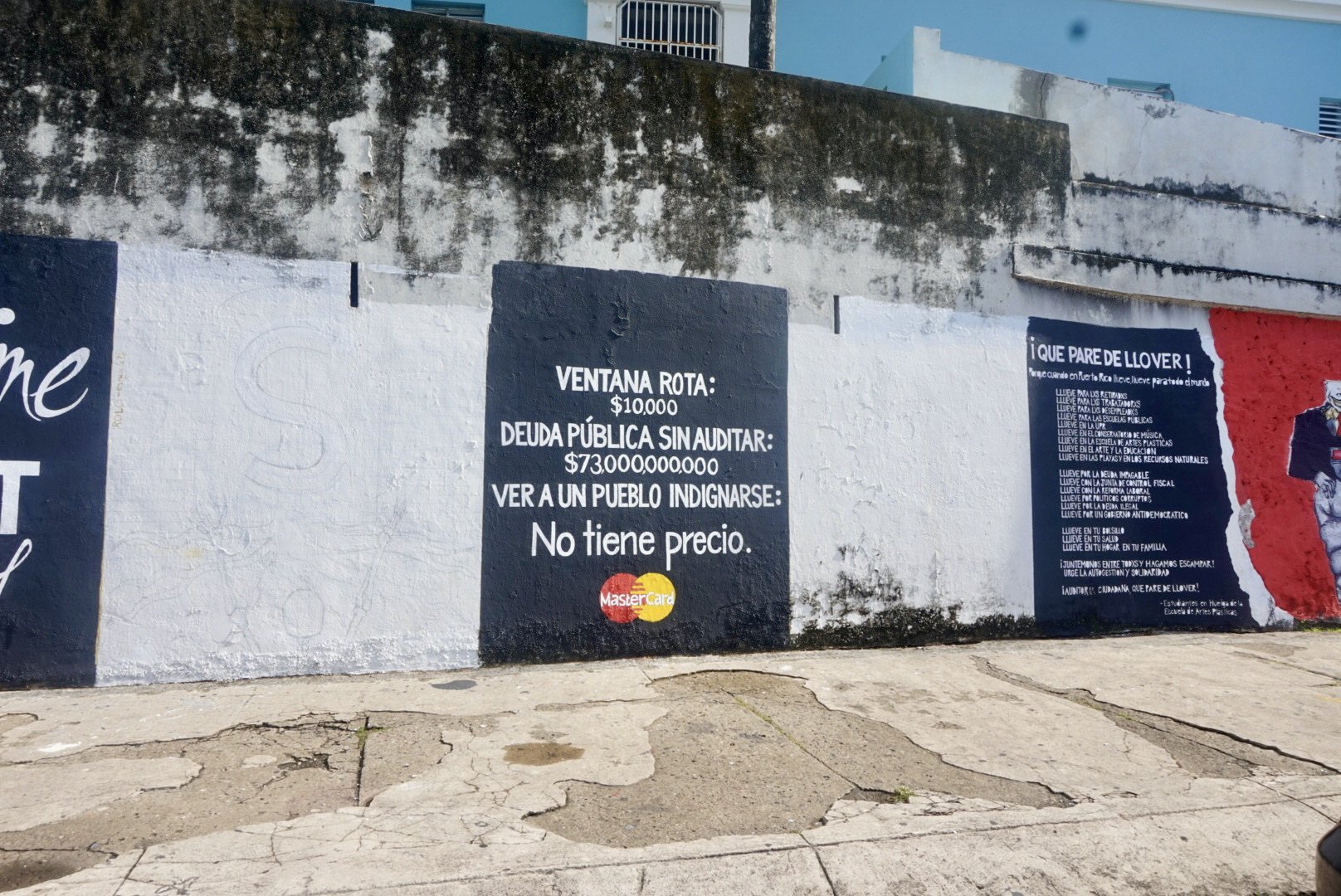

In between La Perla and El Cementerio, we walked by these murals:

Ah. The debt. The unaudited, then $73 billion debt has affected the people in ways that should be considered a human rights violation. Among the alarming, draconian ways to repay the vulture capitalists, the government put in place a sales tax of 10.5%, so residents and visitors alike contribute to paying this debt. Every time I saw a receipt of something I bought, I cringed.

After meditating overlooking El Cementerio and having endured enough reality for the day, we returned to Santurce to rest for the next day’s trip east and then south to visit my dad’s family.

We rented a car and drove to Manatí to spend our third day on the beach in Mar Chiquita. A large cove surrounded by the bluest water and a rocky, crater border.

While my mom laid on the sand, I climbed the rocks with my camera to take a moment of silence. The rich blue water reminded me of Yemayá, the goddess of the sea, the mother of all, the one who supports our self-love, our wounded selves, our healing; the protector, the one who emerges from the depths of her anger to devour her enemies and soak in their blood…

At that moment, I wondered when Borikén would rise again…Two years later, the protests of #RickyRenuncia erupted.

Before heading to Salinas, we stopped by Lechonera Los Pinos in Guavate, Cayey for lunch to eat the crunchiest cuero del lechón, a long-established island dish. A live band was playing as people danced.

Our final stop for the day was Salinas. We went to see two of my wonderful aunts on my father’s side. It was a warm welcome with guanime con habichuelas. My Titi M, who I think makes the best guanimes in the world, showed us how she could now only make the guanimes with white Pillsbury flour instead of harina de maiz because of the high food prices. And she only uses Goya canned beans because cooking gas is too expensive to boil dried beans for several hours.

At least eighty percent of the food Puerto Ricans consume is imported from the United States, in large part due to the outdated Jones Act, which doesn’t allow any other shipment but from the U.S. to enter and as a result hikes up food costs. Even the roasted pig we eat comes from the colonizer.

After eating, Ma and I walked right next door to my other aunt, Titi Z’s house, where my 30-something-year-old disabled, bedstricken cousin, Johnny, was.

We joked and laughed with him for a while and drank the best sweet, rich black coffee Titi Z always makes.

Ma later asked if there were quenepas.

Titi Z took out the longest stick I’ve ever seen and all four of us walked to the tree para pulgar.

We slept over Titi M’s house until we left the next day for Ponce. A few months after Hurricane Maria, Titi Z left with Johnny to Detroit because the healthcare system had severely crumbled, in part due to La Junta’s austerity measures. Conditions were better in the U.S. than in Puerto Rico for a disabled person. Titi Z and Johnny have adjusted after five years and are doing well from what we hear in the phone calls, but we haven’t seen each other since.

Ma and I woke up early the next morning to get on the road. We went to Ponce and then back up north to Caguas, a place I’ve wanted to visit for a long time.

Caguas.

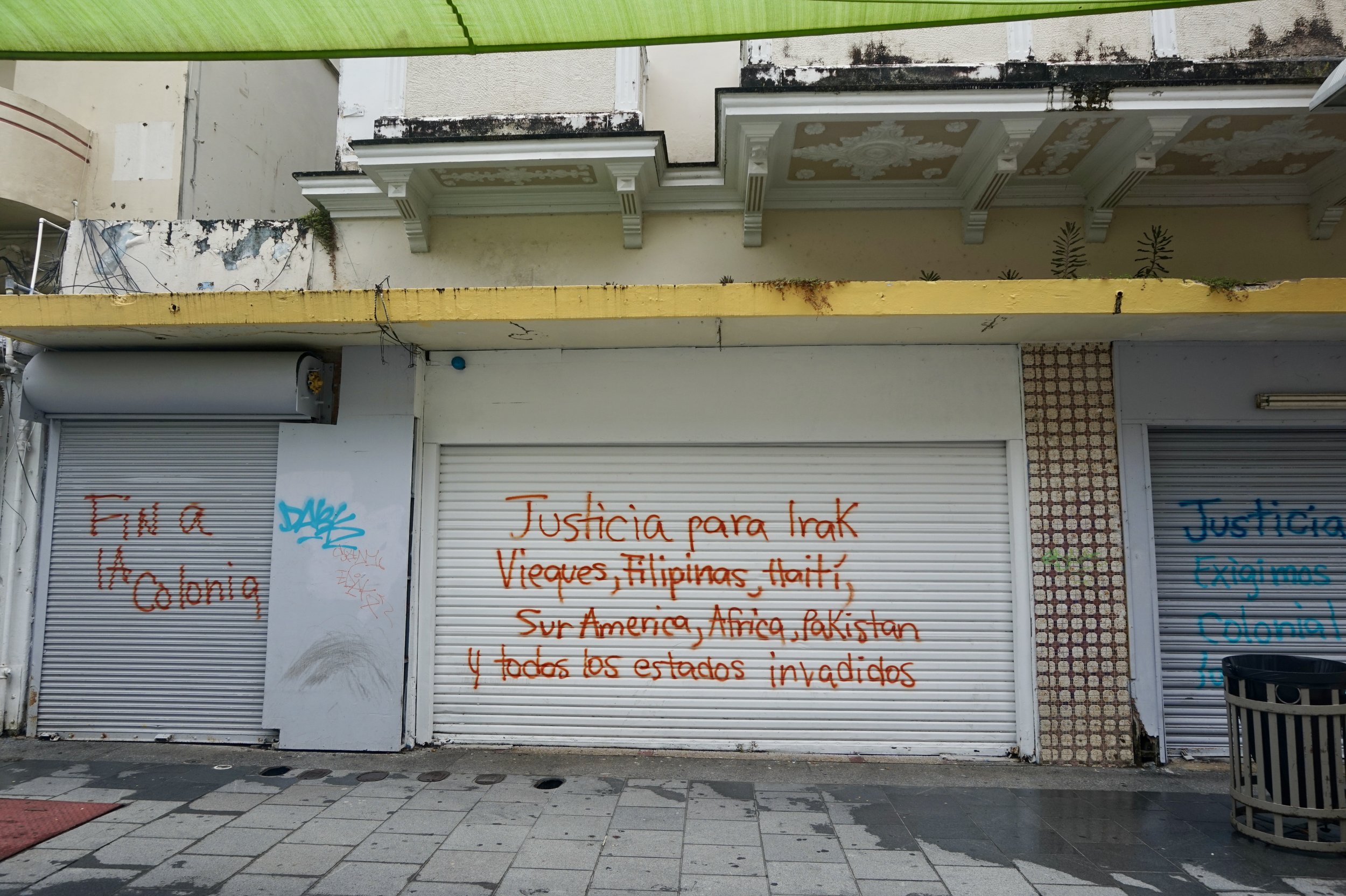

Named after an indigenous chief named Caguax. Known as the quintessential heart of Puerto Rico. Similar to Santurce and Cataño, the town is full of gorgeous murals, but I was shocked that the soul of the country was so empty on a Thursday afternoon.

Prior to Hurricane Maria, an average of 100,000 people have left the island annually but the climate disasters have and continue to accelerate this out migration. Furthermore, other disasters such as the earthquakes, the COVID-19 pandemic, relentless austerity measures by La Junta, and prolonged electricity outages have and continue to threaten the island.

The beautiful murals reflect the once abundant life there.

We drove back up to a hostel in Old San Juan to stay for the night to travel the next day to Luquillo and visit El Yunque, the only rainforest in the national forest system and the residence of the Taíno’s supreme god where they gathered to celebrate.

We hiked the popular La Mina Trail and bathed underneath the mystical 35 feet waterfall surrounded by everyone celebrating. El Yunque struggled to recover years after much of the forest was damaged after Hurricane Maria. Now after Hurricane Fiona, La Mina Trail remains closed. After El Yunque we returned to the hostel in Santurce to prepare for our trip to Vieques the following day.

In 2018, I returned to that same hostel. Along with other guests, I struck up a conversation with the manager, a Puerto Rican woman in her late 30s. She told us that the job had changed her life. Several years earlier, she had been in a severe physically and mentally abusive relationship with a man, but somehow, was able to escape.

In January 2021, Puerto Rico was declared a state of emergency because of its widespread gender-based violence and femicides.

El Violador Eres Tú

2021. Posters on the wall in a restaurant in Santurce saying "El Violador Eres Tú." A response to the 2019 Chilean feminist performance titled, "A Rapist In Your Path" that spread around the world, including Puerto Rico.

I returned once again to this hostel in the summer of 2021, to find out it was owned by someone either American or European. It was greatly run down, a skeleton of its previous existence. The lovely woman I met in 2018 wasn’t there.

On our fifth day, Ma and I hitched a ride with a couple also going to Vieques. Surprisingly, we arrived on the island to stay at another hostel owned by a white American. As a consequence of many factors, including the large numbers of out migration and government tax breaks, opportunists like crypto colonizer Brock Pierce come to Puerto Rico to participate in disaster capitalism. The small island of Vieques, with a population of 8,249 people, unfortunately has fallen victim to this activity.

After eating a delicious seafood stew at a small local restaurant owned by a Afro-Puerto Rican man, Ma and I walked the mini-bosque to the hidden black sand beach, Playa Negra.

Playa Negra

Playa Negra is made possible by the overflow from the volcanic area of Monte Pirata. The mountain is located near a former US Navy communications site, now occupied by the Department of Homeland Security.

I sat on one of the rocks in the secluded beach and exfoliated my whole body with the tiny particles of basalt as if I were trying to cleanse the island from all these realities through myself. Ma just watched me.

In the last legs of the trip, we spent the last couple of days in San Juan, where messages of resistance, oppression, strength, and hopefulness revealed themselves the more we explored. Walking down Paseo de Diego, Río Piedras seemed the epicenter.

We ended our last day drinking coffee at one of my favorite cafes near the water in Old San Juan, Cafe Cola’o.

On the way there, I heard too many tourists acting out, enjoying ‘La isla del encanto,’ but I wondered how it would be if we all went back with open eyes to visit or to stay with love in our hearts for the people and the land. What would it look like if we cleaned up the beach for a day? Or volunteered as a nurse? Or supported farmers in their food projects?

Sitting down in the cafe, I observed my mother’s soft but dry hands with cuts from Palmolive dish soap. She lives in the “land of the free” while dreaming of Puerto Rico and I think:

May my mom, my dad, I and all Puerto Ricans go back home.

—

Epilogue

After the trip with my mom, I went back in the summer of 2018 to participate in a brigade at a farm in Salinas with El Departamento de la Comida and help an older Puerto Rican couple repair their farm’s fence. I also went to a solar panel class and installation workshop at Centro Social El Hormiguero and visited Huerta Semilla at la Universidad de Puerto Rico in Río Piedras to learn about their harvesting and composting program.

The last time I went to the island was in the summer of 2021 with a friend. We did a self-guided food tour in San Juan discovering some incredibly sophisticated and creative cuisine, the result of young Puerto Ricans returning to cultivate the land.

When I go back again, in the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona, I know it will be a different kind of trip, something that is expected in a colonized island.

Damaly Gonzalez is a Brooklynite, Williamsburg-native of Puerto Rican descent that goes by she/her/hers. She is a culture and identity writer who has been published in NBC Latino, Huffington Post, Hip Latina, and LatinTRENDS. Damaly holds a master’s degree in History and Urban Sociology from The Graduate Center, CUNY. Follow her on Instagram @damalyscorner.