A Sonic Exploration of the ‘Nuyorican Dream’

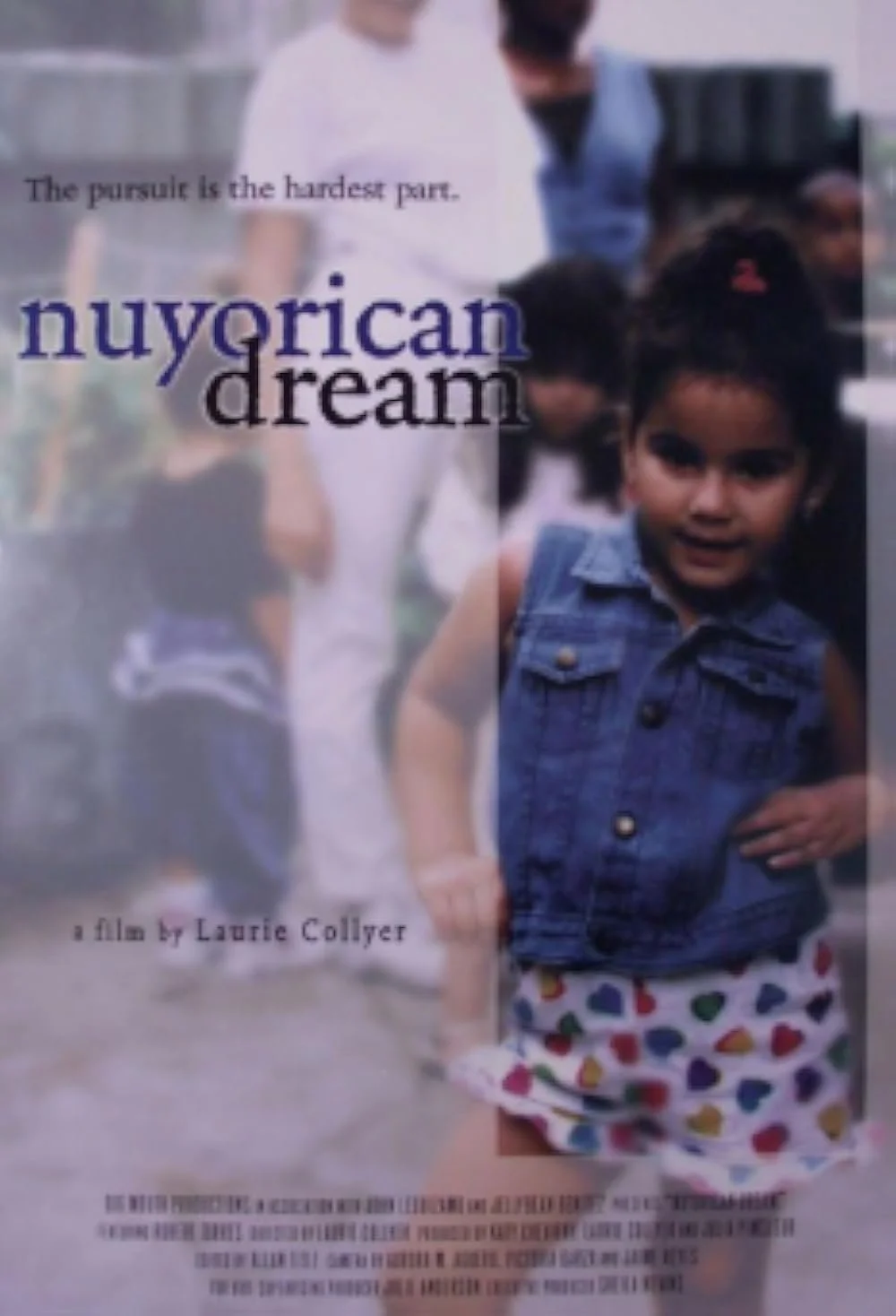

From 1995 to 1999, the Torres family lived in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, where they found their lives taking different directions under the same oppressive system. Director Laurie Collyer documented how they lived and navigated adversities in Nuyorican Dream (2000). The documentary’s soundtrack—a select list of music, ranging from hip-hop to salsa—is just as important to understanding the subjugation of Nuyoricans as the family at the center of this documentary.

“At the turn of the millennium, 25 years ago and a generation ago, Puerto Ricans were in the process of transition, even though Puerto Ricans have always been in the process of transition,” says Carlos Vargas-Ramos, director of public policy, external, and media relations at Center of Puerto Rico Studies at Hunter College. “By the late 1990s, early 2000s, it was clear that the Puerto Rican community was becoming much more heterogeneous in terms of income levels and generational status.” The documentary captures that diversity through the Torres family.

New York of the 1990s had a reputation as a dangerous city with high crime rates, increased unemployment, and continued gentrification from the 1970s. At the same time, the city was flourishing culturally, partially because Puerto Ricans who made up 49.1% of the Latinx population and 12.2% of total residents, were at the heart of a cultural phenomenon in literature, poetry, music, and theater amidst its fourth wave of migration to the city.

The abundant cultural work in the 1990s cemented a unique identity for Puerto Ricans that began to take shape in the ‘60s within the Nuyorican Movement. The term “Nuyorican” defines Puerto Ricans living in New York who integrated both cultural nuances of the island and urban living in a major American metropolitan city. Much of the work during this time expressed the daily hardships three generations of Puerto Ricans faced through a long history of colonization, systemic racism, and discrimination.

One way this manifested was through conversations at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, a community hub that the founders of the 1960s Nuyorican Movement opened in 1990 in Alphabet City. Puerto Rican poets, such as Bronx native María Teresa “Mariposa” Fernández, were one of the voices that gravitated to the cafe and a renewed Nuyorican movement to call attention to not only the hardships of the Nuyorican, but as well as the deep connection to the island and culture. Mariposa’s 1994 poem, Ode to the Diasporican (1994), spoke of claiming and celebrating a dual identity against assimilation and discrimination, a nod to Pedro Pietri’s 1973 poem, Puerto Rican Obituary (1973) that directly laid out the adversities of Puerto Ricans. Both poems challenged the legitimacy of the American Dream for Puerto Ricans, who the government systemically treated as second-class subjects even though they were U.S. citizens. As Robert J. Torres, 30, succinctly says in the film, “The American nightmare is just the opposite of the dream. I think you’re kind of a special person when you come out of the nightmare.”

The shattering of the American Dream is pervasive in Nuyorican Dream, particularly through the Torres family who dealt with drug addiction, poverty, ghetto schooling (students in impoverished communities who end up segregated and receive underfunded education), and prison recidivism, among other issues. Following Robert, the oldest brother, the documentary shows how he navigates the complicated family dynamics with his mom, Marta; three younger sisters, Betty Torres, Tati Torres, and Millie Torres; brother, Danny Torres; and nieces and nephews, providing a snapshot of the ongoing struggles within the Puerto Rican community at large.

Yet, the film also shows resilience in the way Nuyoricans occupied space in New York City. For example, Marta sold thrifted items in front of her building to provide for her family, showing the defiance of Puerto Rican existence despite their precarious conditions, ultimately through hope and love.

While poetry was a hallmark of the Nuyorican experience, locally sourced music from New York and the island like Mobb Deep to Fuerza Juvenil was another means of expression in the 1990s. Not only was music more readily accessible, it further demonstrated the deep Nuyorican impact in the urban landscape and beyond. Each song in this documentary encapsulates the different struggles the community faces, while also serving as a nod to their influence. While not immediately apparent, Puerto Ricans influenced every genre on the soundtrack.

The film opens at night with Robert picking up his younger brother, Danny, 23, from the Q101 bus stop in Long Island City, where the city drops off released inmates. In the background, Queens rap group Mobb Deep’s “Drop a Gem On ‘Em” plays. The 1996 diss track is a response to 2Pac’s “Hit ‘Em Up,” with the duo denigrating 2Pac’s 1995 Riker’s Island prison time, which can metaphorically speak to the contentious battle between the state and its ongoing incarceration of men of color.

The brothers greet each other fondly and walk a short distance to a once-popular café, Twin Donuts, a staple in working-class neighborhoods for its affordability, late night hours, and fresh donuts. Over a coffee, the brothers talk about Danny’s next steps after jail, where he has been in and out since 14. (Recidivism comes up later as Danny sits in front of the camera as an inmate once again, this time in Green Haven Correctional Facility in Upstate New York. Staten Island rap group Wu Tang Clan’s “A Better Tomorrow” plays in the background.)

At the time of the film, 56% of Black people and 33% of Latinos made up the largest percentage of inmates in Rikers, with Puerto Ricans followed by Dominicans disproportionately represented among the Latino population. Among other issues during the 1990s, officials used racial policing and strategies such as “broken windows” and “stop-and-frisk” policies, the War on Drugs, and socioeconomic disparities to target Puerto Ricans. Today, the two groups continue to suffer under racial discrimination as Latinos in Rikers (now more nationally diversified) increased to roughly 34% of inmates and Black inmates make up 58.5% (even though they make up only 22% of the New York City population).

During the 1990s and 2000s, the education system in New York City contributed to mass incarceration through the school-to-prison pipeline. By implementing then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliano’s racist systemic practices, Black and brown adolescents got caught in the system early through zero-tolerance policies that led to suspensions, expulsions, and arrests; increased policing in schools; and schools like Alternate Learning Centers (ALCs) or suspension centers that provided low-quality education and support.

“Most public schools perpetuate the cycle of poverty,” Robert, an educator at the time, says in the film. He was the only member of his family to finish high school and college.

“[There were] improvements [in the late 1990s to early 2000s] among some in terms of educational attainment and employment, but you continued to see a group of the population that remained disempowered, remained in dire poverty, without many prospects for improvement,” Vargas-Ramos says.

With the sounds of Brooklyn-born Hurricane G’s “El Barrio,” a female empowerment rap anthem of a Latina growing up in a rough NYC environment, Robert sits at a large wooden table in a classroom of beige walls, across one of his young Puerto Rican students and her mother and grandmother. It wasn’t the first time Robert spoke to the teenager’s guardians about her behavior, but he reiterated both his support for the family and the importance of education.

While some reforms have diminished the effects of the school-to-prison pipeline, it still harms thousands of Black and brown students across the five boroughs. At the time, Robert was working on designing a program that would offer students an alternative way to learn aside from ghetto schooling. In 2009, he founded Quest to Learn, a curriculum for sixth to 12th graders that incorporates the design principles of games to develop critical skills for college and career readiness.

The family matriarch, Marta Torres, 46, attended school until the fourth grade in Puerto Rico. At 8, she needed to work full-time to support herself and her grandmother after both her parents died from a disease when she was 3. The Puerto Rican trio Los Sabrosos del Merengue’s song “El Riesguito” (1998) talks about the fears of life and the potential failures that can come with making life plans. Similarly, she decided to take a risk in the 1960s and join over a million Puerto Ricans during “The Great Migration” to New York. After Robert gives this background story of his mom, we then see Marta in the next scene, on the street, next to her building, where she sells clothes and jewelry as she explains that the only education she received was to work and survive.

“Certainly, in the mid-20th century [the] government of Puerto Rico was interested in facilitating the emigration of people from Puerto Rico into the United States [to] promote the industrial development in Puerto Rico,” Vargas-Ramos explains. “You’ll see that in the continued decline or the stagnant condition of the labor force participation in Puerto Rico.”

The exodus of Puerto Ricans was the consequence of colonization. As Puerto Rican group Sexteo Borinquen’s 1981 “Canto a Borinquen,” an homage to the island, its people, and beauty plays, Robert tells the story of how the Spanish built a system of exports and then the U.S. brought in corporations, all to exploit the island for financial gain. The consolidation of wealth and resources under colonial rule created pervasive poverty. In 1990, 57% of Puerto Ricans on the island were under the poverty line, while in the mainland U.S., it was 41%.

“The way that perhaps colonization and colonialism is manifesting itself in the emigration and the migration process more broadly for Puerto Ricans is that Puerto Rico as an economy is not able to produce enough wealth to maintain an economy that sustains its population over the long course,” Vargas-Ramos says. While the numbers have decreased, migration from the island continues as colonization has exacerbated other issues like public health.

Drug use within the Puerto Rican community is a long-standing public health issue both on the island and the mainland as a result of poverty, migration, and colonization. Betty, 27, one of the three sisters, sits on a chair in the basement of her mom’s apartment as she recounts doing seven to eight bags of heroin a day. Her story unfolds as the audience hears Bronx native Big Pun’s “Capital Punishment,” where he warns about the system strategizing against everyday people who are already disadvantaged. While this is a grim look at drug usage from someone who was already suffering from the ramifications of colonization, it sends a hopeful message that despite the losses and adversities, there is a chance to persevere.

Tati, 29, Robert’s closest sister, was also an addict and decided to move with her daughter, Heaven, to Orlando to seek a better life. As Afro-Caribbean percussion and chanting emanates from Bronx-raised John Santos and Kindembo’s “Chango,” Robert is on the plane to visit Tati who he eventually finds is still using drugs. This could be a foreshadowing to later in the film when Betty ends up in Lutheran Medical Center’s emergency room for a blood clot from continued drug use. Charizzy and Big Pun’s “Beware” (1998) raps about warnings from the ‘hood.

By the end of the film, Betty is out of the hospital and Tati is back in New York when the whole family—except Danny, who had returned to prison—gathers at their mom’s Sunset Park apartment for her birthday. Papo Vázquez’s Latin jazz song “Coqui” seemingly narrates the family’s beating hearts, de Puerto Rico a Nueva York, as Robert reads his mom a beautiful note of love and appreciation for everything she has done for them despite her own struggles. Marta cries profusely onto his chest. The story of the Torres family is about love and hope and how they care and support each other as best they could through the incredible generational trauma they’ve endured.

The Nuyorican Dream, unlike the American Dream, was never about wealth or individuality. It was a dream rooted in community, resistance against oppression, and the will to exist.

After she blows out the candles, everyone eats cake to Fuerza Juvenil’s Salsa love song “Cuando Acaba el Placer.”