The Salvadoran Speculative With Ruben Reyes Jr.

Latinx creatives have always been engaged in the work of imagining. Dipping into the fantastical, supernatural, or horrific, they’ve long used the speculative to make sense of identities and experiences that seem, in and of themselves, otherworldly.

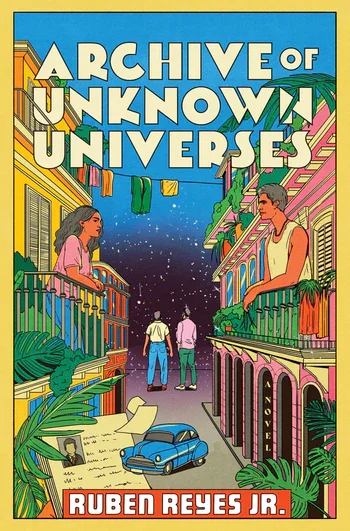

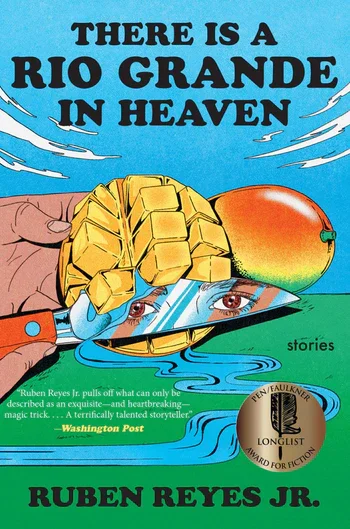

Recently, the isthmus joined the conversation. Ruben Reyes Jr.’s debut novel, Archive of Unknown Universes (2025)—on the heels of his acclaimed debut short story collection, There is a Rio Grande in Heaven (2024)—presents the complexities of Salvadoran migration with speculative wonder.

Intervenxions staff edited this interview for clarity and concision.

Ruben, your writing brings other worlds into existence. What characterizes these worlds?

Categorizing my work is a bit tricky, but I very much pull from the traditions of science fiction and fantasy, two genres I first fell in love with as a young reader. When I write speculative fiction—the best label I’ve found for my fiction—I start with the real world. The speculative elements in my story, whether it’s a cyborg or a device that lets you see alternate versions of your life, are ultimately to ask questions about the world I’m living in. The speculative worlds I build are a way to better understand our world, and (often) its injustices.

What is Salvadoran about the speculative? What is speculative about the Salvadoran?

The condition of Salvadorans, on both sides of the border, feels quite dystopic. Kids in cages, resistance against totalitarian government—these are the things that make up sci-fi movies and novels. That’s what I love about science fiction as a genre: It often asks large, existential questions. The displacement of Salvadorans from their homelands evokes huge questions without easy answers. Since science fiction has always been a vehicle for asking large, existential questions, it has become my starting point to better understand the Salvadoran condition. Genre is my entrypoint.

More specifically, I wonder if there’s something about the physical separation of the diaspora from its homeland that makes us “speculative.” We connect through phone screens, through WhatsApp voice messages. There’s a sense that Salvadoran immigrants can’t return to their homeland, whether for personal, economic, or immigration-related issues. A Salvadoran immigrant might understand how Princess Leia felt when they destroyed Alderaan.

For a while, Latinx imaginaries have been anchored around Chicano and Nuyorican cultural production. The successes of folks like Janel Pineda, Christopher Soto, Javier Zamora, and you show that’s changed. What does El Salvador, or perhaps the isthmus more broadly, do for Latinx?

It’s funny to hear you mention so many writers who inspired me, and who I’m lucky enough to know! It’s such an honor to be writing alongside them.

As Central Americans, we’re often invisible, even in conversations about Latinx people, though I think you’re right that it’s changing a bit. A silver lining is that it frees us a bit to write about our experiences without worrying about what others have written before us. We’re not part of the Chicano or Nuyorican tradition, so even though we can pull or build on the interesting parts of those moments in Latinx literature, we’re free to build our own thing. Right now, it feels special to be in conversation with each other and with the longer tradition of Salvadoran writing in the United States that has flown under the radar and isn’t always included in the traditional canon of Latinx literature.

Your writing doesn’t exactly follow standard narrative conventions: Your books include short stories that repeat, epistolaries, choose-your-own-adventure formats, floating text boxes, transcripts of computer exchanges, and more. Why are these forms necessary to tell these stories?

Realism doesn’t quite work for me, and neither do straight forward storytelling forms. The metatextual stuff—like the letters and text messages—are probably because I’m a digital native. For most of my life, I’ve had multiple ways of communicating, depending if my interactions were in real life or digital. It makes sense that my fiction also makes sense for these multiple modes of communication.

In my fiction, I’m always trying to help readers see our world in new ways, whether it’s regarding immigration, capitalism, or our relationship to technology. Playing with form, and breaking with reader expectations, is one way to do that.

I’m also thinking about Latinx studies scholar Maia Gil’Adí’s work in Doom Patterns: Latinx Speculations and the Aesthetics of Violence (2025). Doom patterns, for her, refers to textual devices (nonlinear narratives, for example) that return the reader to historical violence, despite its speculative rendering. That’s some of the brilliance of literature, for me: estranging the familiar, giving us new eyes to see the systems and structures that surround us, using literary form to reveal social forms.

Exactly! That’s why I’m so drawn to formal play and speculative conceits. And I’m obsessed with that theory. I’m definitely working in doom patterns. When I start a new story, I’m always thinking of ways of conjuring a funhouse version of our world. Other people try to reflect the world in their fiction. I’m more interested in refracting it, forcing a reader to work a bit to see what they’re actually looking at.

From your vantage in the publishing world, are publishers and readers in the second Trump administration showing up for art objects that do that work? Of revealing, estranging, reorienting?

I hope so. At this point, even the most rudimentary attempts to make art are being repressed. I’m worried about the fate of truly revolutionary art, so much of it spearheaded by authors of color. But I do ultimately believe in the lasting power of books and reading, and as long as there are people who are interested in truth, and not just propaganda, the art objects that challenge us will endure. That’s why my day job as an editor feels important these days. I’m publishing history books, ones that will force readers to confront the ugly contours of our country. There’s power in knowing how we failed in the past.

Thinking about the chaos of the moment, I have to bring up AI, too. There are quite a few moments in Archive of Lost Universes when characters use “the Defractor”—that simulation machine that displays hypothetical realities and alternative versions of their lives. For some, it jumpstarts research projects; for others, it eases the trauma of past decisions. Whatever the use, it’s a form of artificial intelligence that changes how the characters think, inquire, remember. What’s it like for you to create and imagine now, as we all teeter on the edge of the AI age?

I’m trying to keep as much of my life as human-centered as possible! I’m worried people are turning to ChatGPT to solve problems the technology simply isn’t equipped to do, which I think is actually how we treat a lot of technology. We want a silver bullet where there isn’t one. So I’m staying away from AI as much as possible. Instead, I’ll go out for drinks with my human friends, people-watch on the subway, and find stuff to write about from those experiences.

With all this talk about creation, tell me about the book covers. María Jesús Contreras designed both, which are works of art in and of themselves.

María is a genius, and I’m obsessed with the covers she illustrated for my books. The process was surprisingly easy. She came up with early sketches, I loved them, and that was that.

Can I ask who you’re reading now? And what you’re writing?

Books I’ve loved lately: Erasure by Percival Everett, Monstrilio by Gerardo Sámano Córdova, and The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector.

I would love to publish another book of stories someday . . . so I’m working toward that. Slow and steady wins the race.