Selling Día de Los Muertos

Whether attributed to our tenderhearted pluralism or, more pessimistically, to a type of brass-necked theft, the United States is, without a doubt, masterful at hawking other nations’ artisanal wares. Our propensity to consume objects from faraway locales—whether we call them “tchotchkes,” “trinkets,” or “souvenirs”—is nothing short of our manifest destiny.

In recent years, our peculiar brand of cultural tourism via consumerism has become downright spooky, especially during the months of September and October. When did U.S. shoppers start spending so much on the Day of the Dead—el Día de los Muertos? The mid- to late 2010s seems to have been the moment when US consumer culture succumbed to a full-blown dalliance with death. Two animated films made it big—2014’s Book of Life and 2017’s Coco—while the opening scene of 2015’s Spectre, part of the umpteenth installment of the James Bond series, saw the eponymous hero on an assassination run during a Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City. Seeing Mexico City (and British heartthrob Daniel Craig) decked out in deathly regalia proved so satisfying that a few years later, a real Day of the Dead procession marched through the streets of the capital city. Seemingly, life can imitate art.

Today, the aisles of Target, Walmart, and even Dollar Tree overflow with skulls, papel picado, and plastic orange marigolds. At a time when the charge of cultural appropriation is weightier than ever, how do retailers signal their products’ authenticity to shoppers?

In his hallmark essay “Todos Santos, Día de Muertos,” Mexican intellectual heavyweight Octavio Paz explores Mexico’s supposed fascination with death. He describes Mexican society’s propensity for manic swings—a nation toggling between feverish, collective rituals and a type of

solitary, catatonic neuroticism. According to Paz, “The frenzy of our festivals shows the extent to which our solitude closes us off from communication with the world.” Death, the ultimate taboo of modern society, is front and center in Paz’s fiesta—a profoundly carnivalesque endeavor that upends the hierarchies that normally structure society. For a brief moment in time, social relations are undone, and we take to heart what connects all of us: our own mortality.

Although Paz’s ambitious toolkit has been rightfully historicized, the celebrated poet and diplomat may still have pointed up a truth: Mexico’s modes of sociability, politics, and communication are often very different from those of the United States. We have an undiminished (even naive) trust in democratic relationships and an unquenchable predilection for optimizing productivity at all times. Our joys are absurdly anodyne—if not downright disappointing: bland escape valves such as “Wellness Wednesdays” or “Casual Fridays” come to mind. Indeed, that grocer Aldi is currently selling a “Day of the Dead” coffee is as incongruous as it is idiotic (fig. 1). If the guiding principle of the true Mexican fiesta is an uncontrollable emancipation of libidinal, violent, even deathly energies that gleefully shatter the status quo, another cup o’ joe in the office break room just won’t cut it. Ditto for paper plates stamped with a skeleton image (fig. 2), or reusable shopping bags (fig. 3), or cutesy catrina table displays (fig. 4).

Thus, that nylon scarves stamped with candy-colored craniums evince a distinct lack of gravitas is evident. Yet, retailers still attempt to capture the pathos of Day of the Dead. In order to sidestep charges of disingenuousness—and underscore their product’s cultural veracity—merchandisers employ a few methods, with varying degrees of success. A provisional study of marketing strategies suggests that they follow a two-step process:

Step 1: Find an artist who identifies as Latinx willing to serve as a spokesperson for a Day of the Dead-themed product line. Forward this individual is as an intermediary—an intercultural emissary or interpreter—who attests to the validity of those wares for sale, and thereby legitimates their purchase among non-Latinx consumers.

In the case of high-end kitchenware retailer Williams and Sonoma, the company’s 2023 Day of the Day goods features Mexican-American cocktail specialist Alba Huerta (figs. 5-7). Similarly, Latino illustrator Luis Pinto was tapped to ideate the Day of the Dead Collection from big box store Target (fig. 8). In the case of Pinto’s collaboration with Target, the artist’s photograph is prominently showcased in aisle displays (fig. 9). As late cultural critic Susan Sontag cogently noted, photographs—distinct from paintings—most definitely “possess a kind of authenticity.” Pinto’s and Huerta’s images are meant to add cultural, even ethnic legitimacy to their respective product lines.

Step 2: Provide consumers information about Day of the Dead so that they can enjoy the celebration, purchase related goods, even while understanding their experience as second-hand.

Effectively, historical and cultural information about the Mexican holiday, usually included in store displays, allows shoppers to participate in what literary scholar Ignacio Sánchez-Prado has described it as “nationalism at a distance.” Williams and Sonoma’s signage highlights this sense of appreciation from afar by describing the company’s dishware as “inspired by the Mexican art of calaveras” (fig. 10). Target’s campaign, in turn, relies on more straightforward, definitional language under the pretense of teaching customers a few words in Spanish—ofrenda, pan de muerto, calaveritas de azúcar cempazúchitl, and papel picado (fig. 11). In a world awash with images, words assume a more sophisticated, erudite meaning. The signage in Williams and Sonoma and Target aim to entice middle-class patrons who imagine themselves as culturally savvy. The fact that the Day of the Dead merchandise at Williams and Sonoma is fabricated primarily in Turkey—while Target’s offering comes mostly from China—matters little.

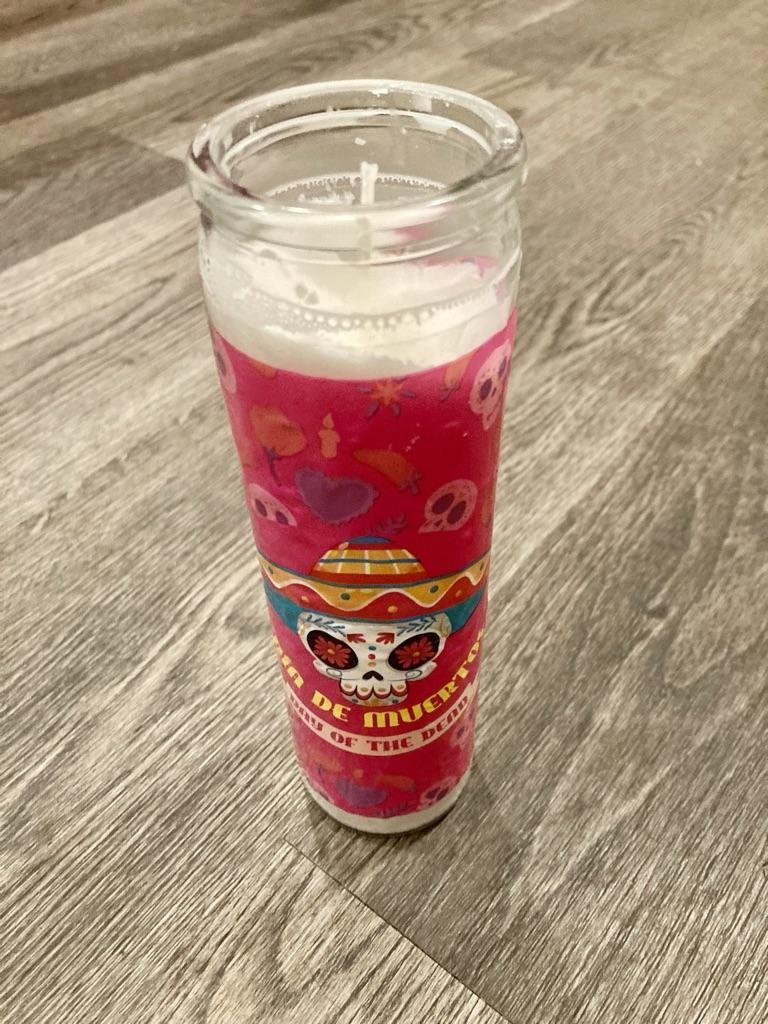

During a recent errand run, the only Day of the Dead product that I found actually made in Mexico was a candle from Dollar Tree (fig. 12). This was my only purchase for the holiday. After all, even if I accept that ancestral heritages are truly a thing of the past—and even if I acknowledge that all the traditions we have left are invented, constantly changing, and distinctly hybrid—we might as well remunerate those who first created the cultural artifacts we now universally enjoy.

Kevin M. Anzzolin, Lecturer of Spanish, arrived at Christopher Newport University in fall 2021, where he teaches a wide range of classes in Spanish and English. His monograph, Guardians of Discourse: Literature and Journalism in Porfirian Mexico, is currently under contract. His research focuses primarily on Mexican narrative from the 19th- to 21st centuries. His publications have appeared in Letras hispanas and Studies in Latin American Popular Culture.