“We Were There”: The Community Fires Back in La Manplesa: An Uprising Remembered (REVIEW)

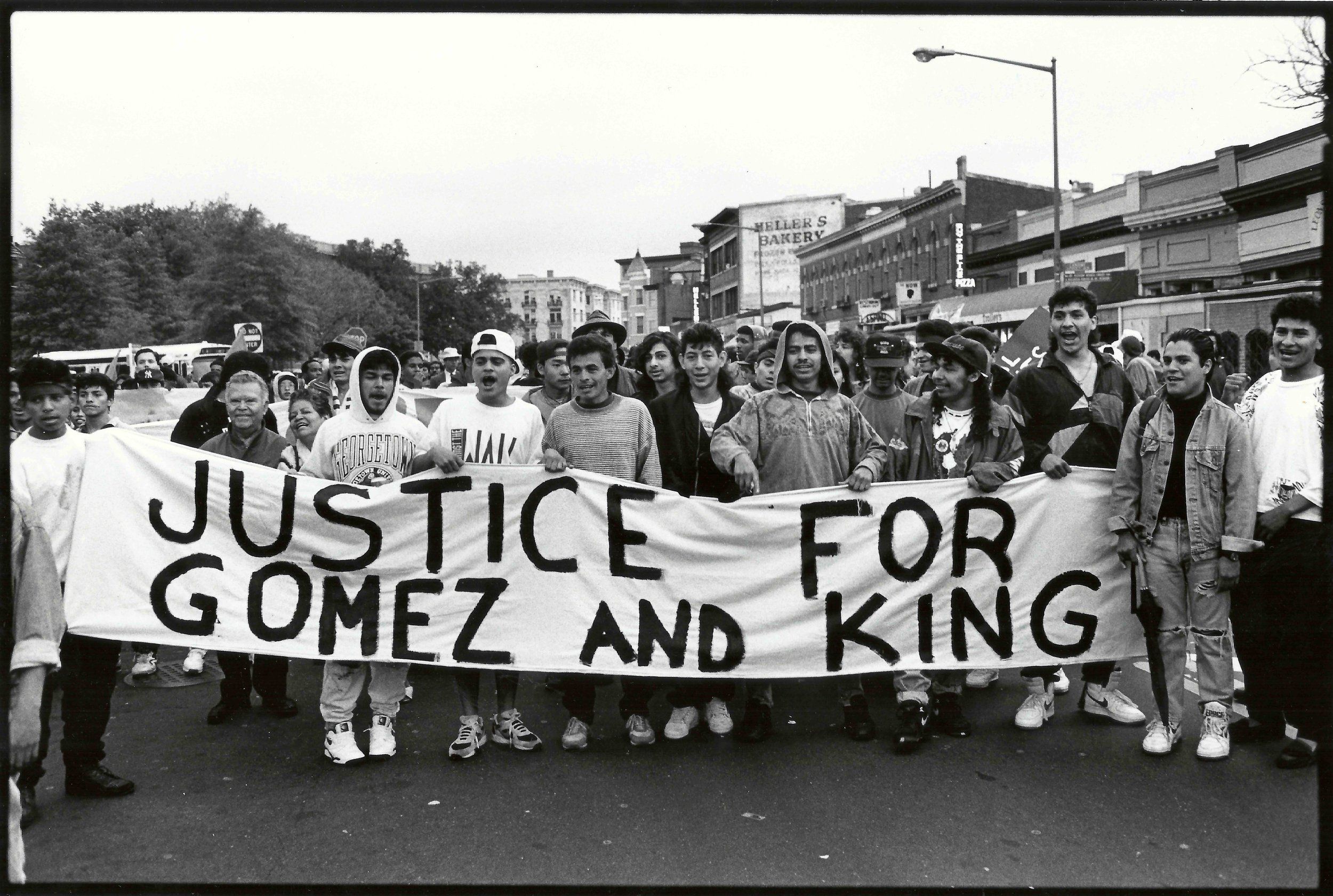

Ellie Walton’s documentary film La Manplesa: An Uprising Remembered (2021) tells a people’s (hi)story of the Mount Pleasant disturbance or uprising, which took place in the Nation’s Capital on May 5-7, 1991. More precisely, on the evening of Cinco de Mayo, the DC Metropolitan Police were called to the intersection of Mount Pleasant and Lamont Streets NW, where a Salvadoran man, Daniel Gómez, was acting disorderly under the influence of alcohol. After an attempt to subdue and arrest him, a Black woman police officer at the scene shot Gómez. As depicted in the film, the shooting unleashed not only days of fighting between authorities and people in the streets, but also the long pent-up rabia and tensions of communities largely marginalized, neglected, and abused in the District of Columbia. The uprising in Mount Pleasant (La Manplesa), which quickly spilled over into bordering Adams Morgan and Columbia Heights, was no small event, but an all-out war against the same conditions of U.S. imperialism, systemic oppression, and police and military violence, which had brought Salvadoran refugees to Washington, DC. Salvadorans were “here” because the U.S. government has been “there,” intervening in the Central American isthmus since the nineteenth century. La Manplesa does justice to the telling of that monumental but little-known uprising and the long covert story of the struggles of Salvadorans, African Americans, and other disenfranchised communities in Washington, DC.

Long known as Chocolate City for the historic presence of its Black residents, Washington, DC, in the 1980s, saw the arrival of thousands of Salvadorans and other Central Americans fleeing civil wars in the isthmus. Beyond traditional sites of migration like Los Angeles and San Francisco, Salvadorans in DC settled in and around Mount Pleasant, where shops, businesses, churches, schools, housing, services, and employment opportunities attracted, if not welcomed, the newcomers. By 1991, the Latinx population in the District had grown to 10 percent, with Salvadorans comprising the largest, but most invisibilized group. In the words of Quique Avilés, DC-based-Salvadoran poet and co-producer of the documentary, La Manplesa was, and remains to this day, the epicenter and heart of Salvadoran Wachinton. Today, more than one million Salvadorans reside in the Washington, DC metropolitan area and the DMV (Washington, Maryland, and Virginia), and yet people are still surprised to learn that we are here.

The first full-length documentary to represent the Salvadoran diaspora and the Mount Pleasant uprising in the District of Columbia, La Manplesa draws from a range of material hidden away in newsrooms, public archives, and personal memories. The film uses footage from local news reporting, photographs, and what appear to be home-movies, and mixes them with present-day spoken word performances, street theater, music, songs, testimonios, and interviews with people who “were there,” in the words of “memory-keeper” Pepe González, as he recounts the uprising in the neighborhood where he was raised and still lives. “Memory-keeper” is the term used in the film to honor and acknowledge “the neighbors, community leaders, artists who stood up for the rights of the Latino community in DC, and worked tirelessly to build organizations to meet their needs and amplify their voices.” Artists, activists, and community leaders featured in the film include Quique Avilés, Pepe González, Lilo González, Sami Miranda, Ronald Chacón, Rick Reinhard, Pedro Avilés, Lori Kaplan, Lupi Quinteros-Grady, Arturo Griffiths, Roland Roebuck, Jackie Reyes-Yanes, Butch Chappell, Felix Dilone, Haydee Vanegas, and others who give voice to past and present struggles of the Latinx and Black communities in La Manplesa.

Filmed in the streets, homes, porches, and front stoops of the neighborhood, these memory keepers recreate scenes of the uprising and its aftermath for new spectators living in the moment of #BlackLivesMatter activism and the COVID-19 pandemic, as seen in present-day scenes of mask-wearing protestors. The uprising in 1991 is infused with imagery of the continued struggle for racial and social justice. The documentary stitches historical images and reflections of artists and community members in Mount Pleasant, who describe the shooting of Gómez for which there is no visual documentation, only word-of-mouth testimonios.

To recreate the scene of the shooting, the film hauntingly uses stop-motion animation in monochromatic colors to represent scene-by-scene images of a drunken figure wobbling on a street corner, taking off his belt, and falling to the ground as he is approached by an armed police officer aiming a weapon. There is a dispute in the film among those interviewed as to whether Gómez was handcuffed at the time of his shooting. What is certain is that he was shot and word on the street spread quickly. In the animated recreation, broad red brush strokes mark the blood splattered on that day and on that corner. The interpellation of stop-motion animation at the center of the film powerfully fills in the gap in representation that clouds accounts of the killings of Gómez and many Black and Brown people, past and present. As Avilés says, “Things get lost; memory is erased. The role of the artist is to create a file of memory.” La Manplesa does just that: it (re)creates the uprising from multiple points of view and memories and sets them on film.

Connecting present and past memories of La Manplesa, spoken and visual testimonios are threaded together with captioned stanzas from Avilés’s poignant poem titled “Barrio” (1992). Lines from Avilés’s poem serve as transitions between film segments and figure as ghostly apparitions of the hopes and dreams of people, who, pushed to the brink, say basta to systemic oppression and rise up as they did in La Manplesa. Words, however, are not enough, Avilés reminds us, and “trying to write things about this place...is difficult, very difficult.” Thus, Walton’s long-awaited and needed documentary may serve to jump-start DC Latinx conversations around concrete solutions. After the uprising, for example, the Latino Civil Rights Task Force was established, along with the allocation of city funds for programs, services, and assistance to the DC Latinx community, always, however, at risk of being cut and phased out.

In La Manplesa, Pepe González and the other memory keepers tell their personal stories of tear gas raining on them and the police turning their weapons and batons on the people, which they do so again in the final scenes of the documentary. In the end, spectators are called to connect the dots between uprisings for social and racial justice, and the #BlackLives Matter demonstrations that erupted in the Nation’s Capital in 2020, following the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black and Brown Americans. What is made clear in the film is that the police and National Guard can, have, and will turn their firepower on protestors. As memory keeper Roland Roebuck says, some are “more loyal to the concept of Blue” than to the red of our common humanity. In the name of pueblos and people in struggle, La Manplesa seems to echo Salvadoran revolutionary poet Roque Dalton’s call to action. In “The Cops and the Guards,” the people, tired of authorities firing on them, turn the tables and fire on the police. In La Manplesa, the people, tired of constant harassment, violence, and willful and woeful neglect in the streets of Washington, DC, finally fire back with their voices and bodies. In the end, Gómez’s killing is not a singular act, but the collective story of the resistance of communities, barrios, and peoples across the Americas.

—

La Manplesa: An Uprising Remember will broadcast nationally on PBS on October 6th, 2022 as part of the new season of America Reframed. Additional in-person screenings are planned for Fall 2022. See the full schedule here and watch the extended trailer below.

Ana Patricia Rodríguez is Associate Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the U.S. Latina/o Studies program at the University of Maryland, College Park, where she teaches classes on Latin American, Central American, and U.S. Latina/o literatures and cultures. She has published widely on Central American transnational cultural production. She is the author of Dividing the Isthmus: Central American Transnational Histories, Literatures, and Cultures (University of Texas Press, 2009) and co-editor (with Linda J. Craft and Astvaldur Astvaldsson) of De la hamaca al trono y al más allá: Lecturas críticas de la obra de Manlio Argueta (San Salvador: Universidad Tecnológica, 2013). She is completing book manuscripts on trauma and (post)memory in the Central American diasporas, and Central American cultural production in the DMV (D.C., Maryland, and Virginia). She dedicates a great part of her time to working on community-based projects with local immigrant communities in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area and serves on the boards of Teach Central America / Teaching for Change, CARECEN-DC (Central American/Latino Resource Center), La Casa de la Cultura El Salvador, and the Smithsonian Molina Latino Gallery opening in 2021.