Just Like Yesterday: The Young Lords at DePaul

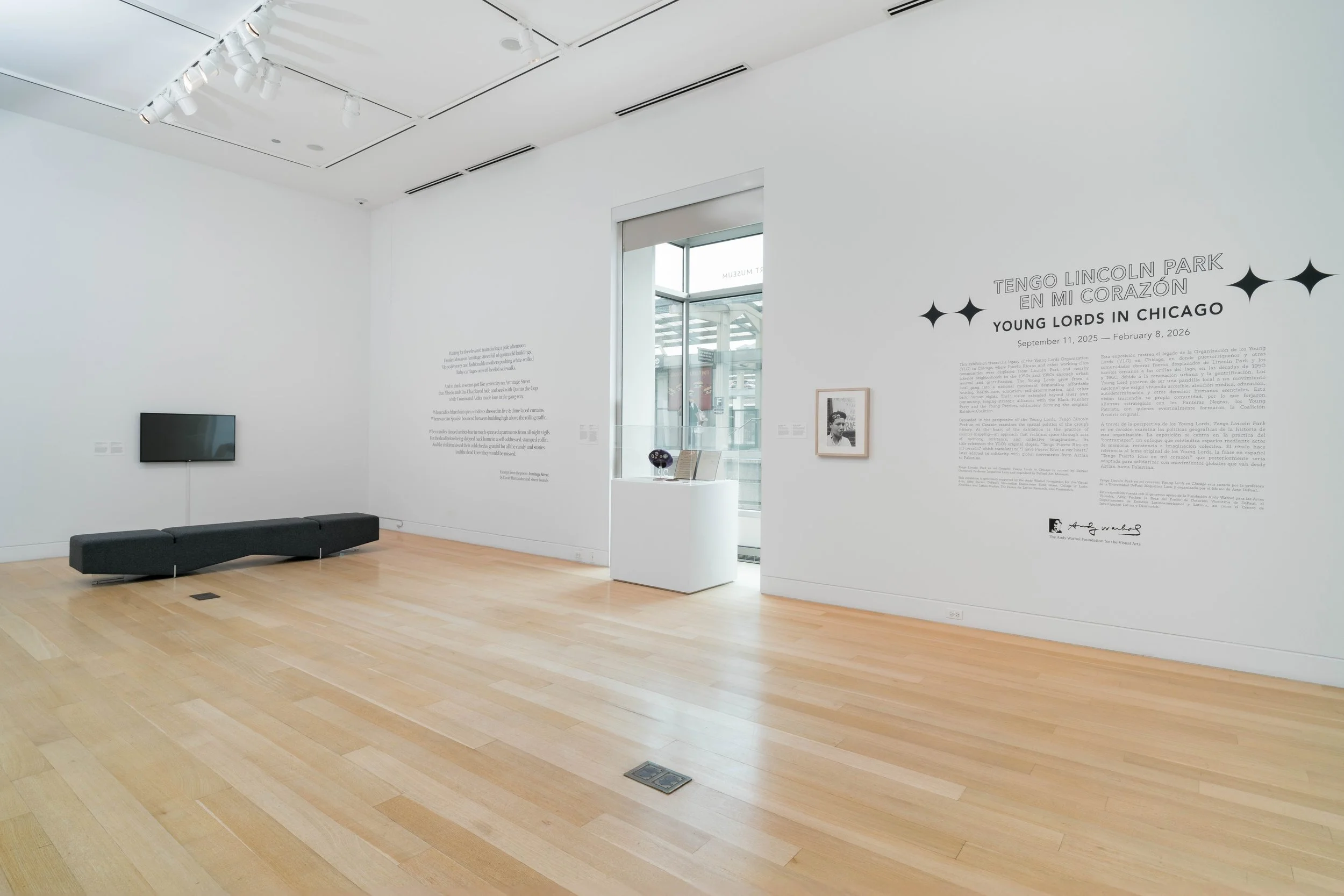

Vivacious histories ripple across a two-room, one-hallway exhibition with pronounced and demanding attention. Curated by Depaul University professor Jacqueline Lazú, Tengo Lincoln Park en mi corazón finds inertia by partnering political imagination with historical reality. Tracing the emergent activism of the Young Lords Organization (YLO)—known for its transformation from a Puerto Rican street gang to a provocative community-based movement—in the Chicago neighborhood of Lincoln Park, the exhibition evidences the group’s struggle for equality in the 1950s and ‘60s amidst forces that sought its eradication through urban removal at every turn. It is a careful balance between archival ephemera, a multiplicity of past sociopolitical inscriptions alongside contemporary artistic manifestations, that echoes the cultural, visual, and material lineages of the YLO.

In the first room, photographs, rare video footage, and pamphlets carry the past forward. Upon entering the space, four pictures, taken from the series A Lens on the Barrio by Carlos Flores, capture a delicate nostalgia. Young men, women, and children scatter the sidewalks, a ludic vision of a community in bloom. In one snapshot, young men gather around each other to pose for the camera. The group of seven is well-dressed, hair perfectly combed and uniform. Two of them sport cool shades, while the rest let the sun wash over their eyes. Individually and collectively, they possess an exquisitely styled aesthetic; joy exudes from the frame, rivaling their charismatic but suave youth.

On a different wall, an excerpt of a poem from Armitage Street by David Hernández and Street Sounds looms over the space. Next to it are some of the personal belongings of José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, founder and chairman of the Young Lords. Across, a well-crafted timeline of key moments in the YLO’s history appears on top as a visual, primarily photographic narrative, and below as an equally well-organized display case with textual records. The images, documents, and accompanying didactics offer a composite look at these periods. They reflect a sustained involvement within a community—an exuberant residence. Simultaneously, however, they also foretell a narrative of forced removal of Puerto Rican tenants from Lincoln Park—at a time when their vibrancy was visible in the neighborhood—and the cultural skeletons that haunt the site. But to read both the history and the curation in this way is to misinterpret the striking resonance of a people and overlook an insightful methodological apparatus. Where the former interpretation suggests an active futurity filled with possibility, the latter formalizes passive anteriority with finality.

In either case, the conclusion remains tantamount because, like similarly oriented exhibitions where research is not simply part of its construction but an explicit presentational tactic, material objects are activated with the pedagogical goal to teach audiences. To be a viewer within this space, then, is to be a learner. Here, objects are not historical, but they do historize. They concern history; they are of, about, and in history, but are not concretized by the tendency that history has (and those who wield it) to pronounce an entity static, devoid of any possible progression. Instead, the artworks and related documents are comets that project imaginaries forward. Such a determination is one of the brilliant argumentative currents that takes hold in the space, one dedicated to evidencing the history of a neighborhood, the communities in it, and their legacies as enduring. It is this triplet, one devised among organization, geography, and procedure, that allows for the digestion of urban as well as spatial politics.

Contemporary works like Areli Lupercio’s YLO 50th Anniversary Logo, which draws explicit referential connections to organizational, national, and cultural legacies, reifies the notion that here, history continues forth.

At the heart of the show, the conceptual tool of counter-mapping, “an approach that reclaims space through acts of meaning, resistance, and collective imagination,” as the wall-text explains, serves to explicate this very goal, in turn articulating the gravity behind the mechanics of empowerment, ethnic equality, and racial justice championed by the YLO. While maps increasingly organize and engineer a trajectory to a desired location spatially, the cartographic tool not only broadly captures the physical makeup of a space but also takes a snapshot of what existed at that precise moment in time.

Amended with the antagonistic determinant, “counter,” the phrase speaks to either a radical strategy of chronological reversal—turning back time—to evidence places and spaces that once existed or have since evolved, or a geographical subversion—taking back site—an ethical insurgency.

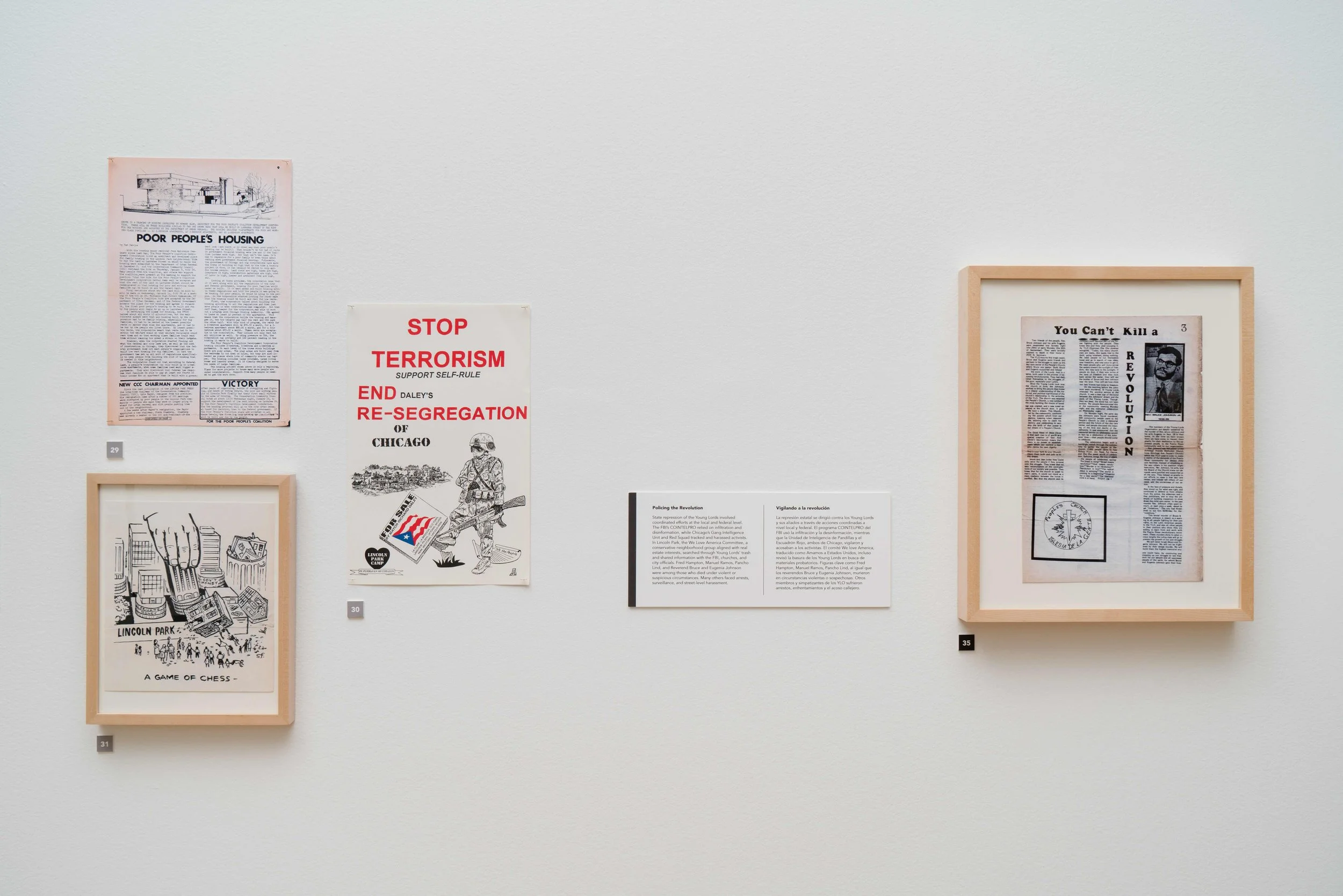

In many ways, such procedures describe already evident practices (solutions) that the Young Lords formulated, leading the group to create the People’s Sanctuary, take over the McCormick Theological Seminary (renaming it to the Manuel Ramos Memorial Building), and transform People’s Park. Coupled with the morpheme “-ing,” the tool, as explicitly referred to in the curatorial framing, converts participatory engagement into epistemic reconstruction. Positioned together, a counter-map acts as the external blueprint that can then be placed onto a previous map, a “counter” navigation that overlays and adapts how space is read. The logics, therefore, enact a sight that encounters site twice. Expounded through this lens, multiple geographical/temporal vantage points reveal the architectural violence of urban transformation. Appropriated buildings, disappeared or killed community members, and occluded events are the structural foundations only legible through the superimposed image of a counter-map. Rupturing the present, the past tears through.

Counter-mapping, then, describes not only the ontological adoption by viewers but also individual and collective efforts of specific items within the exhibition to enumerate a multiplicity of images, each grabbing hold of the next. This relational network produces a web of peculiar but interpolated meaning, a mediated form of layering that reverberates by way of its centripetal force. Within the context of the exhibition, one can find resonance between these visual alliances and YLO’s affinity to endorse and take part in cross-racial and ethnic groups like the Black Panthers and the Young Patriots (collectively known as the Rainbow Coalition). Intersectional partnerships stand out elsewhere. Sam Kirk’s newly commissioned The Truth About Lincoln Park (Remix) incorporates members of the Young Lords and Lucy Parsons, an organizer who fought for workers’ rights during the 19th and 20th centuries across multiracial lines. Endlessly bright with color and iconography, the expansive mural is itself a map, a panoramic reflection of places, people, and things that should never be forgotten. In Kirk’s map, longitude and latitude languish against the locating power of memory.

The collective emergence of images destroys the very walls they exist on, a heuristic that attempts to pull attention away from the art itself and instead focus on how the surrounding neighborhood environment has changed throughout time. A chronographic return to the 1950s and ‘60s, rampant with perspectives that saw governments askance, observant to their insidious bureaucratic violence, speaks to the dynamic and sophisticated prowess of the show, particularly as it parallels the contemporary moment. Transportation and transformation command.

More than anything else, this is the telos of research forward shows, accumulated with pedagogical tools, a sumptuous immersion that subverts the very pretext of an art exhibition and instead radicalizes the perimeter of the room to plant viewers into a world unknown (or one revisited). More contextualized classroom than pure display, more engaged participant than idle viewer, politics energizes rhetoric. Theorized in this way, counter-mapping is one tool with evolutionary potential to configure the pedagogical parameters of art spaces and the objects within them. Taking us to the very precipice of curation’s and art’s effectivity—photographs, posters, documents, and more—purposefully blur reality.

Perhaps no work is as persuasive in this extra-communicative hybridization of realities than the video-work WSTP Radio by Arif Smith with Rebel Betty, commissioned specifically for the exhibition. Songs by Santana, Madlib, and Aretha Franklin burst from the speakers, filling the spliced historic video segments and photographs of Young Lords and Black Panthers with quasi-soundtracks. Music builds, crescendos sweep, and rhythm animates the bodies of protesters meeting corrals of blue-collared Chicago Police officers as they spill out of white vans. Typographic moments that fill the screen with words like “Chicago” are reminiscent of opening credits scenes, while other visual elements like animated Puerto Rican flags or the layering of historic posters produce a fusion between the historical and the contemporary. At times, the audio-video collage feels like an action-packed thriller. The heightened cinematic moments are tenuous and as nerve-wracking to view (presumably violence is coming, though we never see any materialize) as they are enticing and quixotic.

This time, however, there is no fiction, but only stark reality. In its entirety, the work is one never-ending opening score that comes right at the conclusion of a viewer’s journey—another subtle counter, a poignant audio-visual repartee, a rallying sendoff into the world.

What does one see when exhibition walls collapse and the only view one has is of the past, where the present used to be? My own vision has changed. Today, I see through Armitage Street. Instead of the “up-scale stores and fashionable mothers pushing white-walled baby-carriages on well-heeled sidewalks,” I see “Alfredo and Cha-Cha play[ing] hide and seek with Quinto the Cop while Cosmo and Aidita make love in the gang-way.” As I look down the street, “the quaint old buildings” glow while the rumble from the train above swiftly quiets. Not new, but returning, are the sounds of soft static frequencies, “radios blar[ing] out open windows dressed with five & dime laced curtains.” And an atmosphere of “staccato Spanish bounc[ing] between buildings high above the rolling traffic,” fills my ears to the brim with familiarity. For someone not born with Puerto Rico in their heart, counter-mapping has given me a path, or rather, a plan to find it: “And the dead knew they would be missed.”