Adaptive Reuse: Precog in Conversation with Tiempo de Zafra and diSONARE on Experimental Publishing

If we play with the old axiom that form follows function, it should follow that independent, experimental publishing will be as varied and innovative as the ways that information is disseminated in culture. Last spring, Florencia Escudero and Gaby Collins-Fernández of Precog Magazine spoke with Edgar Garrido and Stephanie Bezarra of the Dominican Republic-based collaborative Tiempo de Zafra, and Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola of the Mexico City- and NYC-based journal diSONARE. In the conversation that follows, we discuss publishing as textile and social patterns, popular icons and signs whose intended messages fade with their circulation, the effect of colonialism and diaspora on legibility, and how to participate in the re-creation of meaning.

Florencia Escudero (FE): Hello everyone. We wanted to begin this by asking you to briefly introduce yourselves and what you do.

Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola (LHG): diSONARE is an editorial project made by me and my partner, Diego Gerard Morrison. diSONARE started because we wanted to find a place to publish weird bilingual poems and essays, and publish both our friends from Mexico City and other places, to start a community where people from Latin America and the U.S. could collaborate. We thought a journal was a good vehicle to create nourishing and syncretic communities. Diego is a fiction writer and a translator, and I am a visual artist and a poet. Because we work in many mediums, we were thinking of translation beyond the medium of words, or literature. A translation of mediums: in between spaces and spaces of friction. So diSONARE is an experimental journal that we started in 2013. We publish one journal per year, and we also do many other projects connected to the journal, including a sound archive, workshops, radio, and performances. Simultaneous to the editorial project, we have many other projects going on. Some of them start and end and start again. It is adaptive and fluid.

Stephanie Bezarra (SB): Edgar and I, as Tiempo de Zafra, have been working together since 2016.

Edgar Garrido (EG): We met in New York and started working collaboratively. Tiempo de Zafra at those early stages wasn’t just me and Stephanie. I was also working with my father, who is a tailor and helped us make garments. We were sourcing whatever we could find, because we didn’t have the money to buy fabric and other materials. We would go to places like dollar stores and secondhand shops. Eventually, Stephanie and I put together our first collaboration. We brought pieces that we had worked on with my father and we installed them in front of Banco Popular on 181st in Manhattan, where there is already a big street market. The vendors are all immigrants, so at the time, there were Mexicans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans. It’s different now, but when we were there (and before then, when my grandmother would take me up there), it was this place where you could find all this weird stuff you couldn’t find elsewhere. When we set up our pieces, we were right next to this person selling dollar makeup and fake purses.

SB: We installed the clothes in the middle of the market as a conversation starter. We weren’t really trying to sell anything, we just wanted to talk to people about what we were doing.

EG: Through that we realized that we wanted to be able to do things informally, that there is also something formal in the informal, in the behaviors and attitudes that you encounter. So we decided to keep working alongside the things that inspire us. From that day on, we’ve been collaborating on everything. Then we moved the studio to the Dominican Republic and started collaborating with artists here as well.

SB: In relation to publishing, it’s important to note that before we became a full-blown design studio, we were making more “traditional” art, and also making publications, prints, and zines, in order to get the word out about what we were doing.

EG: It takes time for a project to be ready, but we had la inquietud de hacer cosas, y cuando tú tienes esa inquietud, tú lo haces como sea. When we look back now, it’s clear that all those things are a part of our story, but at the time, we just wanted to make stuff with the materials we found. From there, people started to commission us for certain things, like garments.

FE: You have a collection of religious pamphlets, and you also incorporate a lot of graphic elements into your garments. Can you tell us about this collection?

EG: The culture here es muy religiosa—hay católicos, evangélicos, y cristianos. They always find a way to get their message out. There is this marketing behind the Word of the Lord that is very robust. Here [in DR] it is very interesting.

SB: And you find these pamphlets everywhere—on the floor, people pass them out to us.

EG: We have a pamphlet that a group was passing out that says “La Visa…Al Cielo” with the American thing. In Dominican Republic, for most of the people who haven’t left, one of the dreams is to get your visa and get out of here. The Latin American thing, to want to leave: “nos vamos para América, una vida mejor, un futuro mejor.” There are so many. We have another that says “Lo Que El Dinero No Puede Comprar.” When you look inside, there’s a message: “Placer, pero no el amor/ un esclavo, pero no un amigo/ una mujer, pero no una esposa/ una casa, pero no un hogar/ alimento, pero no apetito/ medicinas, pero no salud/ diplomas, pero no cultura/ libros, pero no inteligencia/ escuelas, pero no educación/ tranquilidad, pero no paz/ la indulgencia, pero no perdón/ la tierra, pero no se compra el cielo.”

LHG: Incredible.

SB: You can relate to it, whether you’re religious or not. A lot of what we do with them is taking them out of context, because people are less likely to pay attention to them when they have this religious connection.

EG: The landscape here also has a lot of graphic elements. People don’t buy an awning for their businesses, they will paint right on the front of the building. I want to show you another pamphlet, which reads, “Lo tenía todo, pero le faltaba Dios”—and it’s a picture of Michael Jackson! When I saw this, I was like, ¡se pasaron!

FE: I love the idea of this unknown person cranking out the graphics and drawings.

EG: We started to appropriate these pamphlets and texts. The same way that the garments are deconstructed, made from various found and recycled garments, we started to deconstruct the messages.Tiempo de Zafra is very inspired by this graphic landscape—it’s not just about wanting to make a graphic T-shirt. Our environment is already that jumble of messages and objects.

LHG: It sounds like you are reading the environment. I often ask myself what is reading, and what is writing? These objects and texts you find are almost like divination systems, or messages talking to you. Like a Tarot deck unfolding in public space.

EG: Exactly. Tú te encuentras mensajes que maybe te guían. Sometimes, if I find one and we already have it, I’ll place it somewhere donde yo sé que alguien va a pasar y se lo va a llevar. Yo me imagino que hay muchas más personas que hacen lo mismo.

FE: That starts to happen in WhatsApp, too. Does anyone have that relative that will pass along these little graphics that read, “Dios te bendiga superpowers today.” It’s on the web now — there are some relatives that will only communicate through those graphics.

SB: It’s so interesting to see how that visual communication is evolving between generations, and how it will keep evolving. The younger people use those stickers, and our parents or uncles, will say “Buen día, que Dios te bendiga,” with the ClipArt caterpillar on a sunflower or something.

EG: I don’t think that the pamphlets are so different from the stickers, in terms of what people want to communicate.

Gabriela Collins-Fernández (GCF): In gathering ideas for bringing you all together around independent publishing and collaboration, there were a few markers that Flo and I came up with that could be useful to guide the discussion. Publications have to do with the presentation and dissemination of kinds of knowledge. You have both spoken about this already a little; Lucía in terms of translating beyond mediums, and Edgar and Stephanie in terms of this reading of landscape. What centers of knowledge do you want to bring forth and communicate?

There is also the question of reproduction and type. In the case of diSONARE, that clearly happens through the journal itself. For Tiempo de Zafra, you could talk about reproduction in relation to a pattern (for making garments)? The pattern itself could be talked about as a kind of publication, or print. There are different kinds of ethics and goals that you have in terms of the reproduction of objects and forms of knowledge. Does being independent play a role in these systems and actions? Are you working in opposition to particular centers? Does this have something to do with what Edgar mentioned earlier, the formality of the informal?

LHG: Any project that has formality can give you structure. But informality gives you another structure, which is more unpredictable. In diSONARE, we are excited about the unpredictability of things. We give agency to things that are more outside of ourselves, the in-between spaces of collaboration or collision; those nodes of coherence that are unpredictable. We also ask ourselves: what is legibility? Who do you have to be legible to? Do you want to be legible, or illegible, which is another way of generating questions and forces which propel you forward. I like that rubric of reading the environment and letting these new forms of communication guide you, expanding into a more layered complexity. What sprouts out of that?

GCF: Are there particular ways you want to be legible or illegible, or places that you want to read this way? Is this an abstract, as well as a practical, concern?

LHG: I think time has to do with it. I’m very interested in the future, and perceiving the past as a future. We don’t know so many things about the past. I am very interested in figures of literature or art in Mexico and in other places that haven’t been explored or seen. In Latin America (maybe everywhere) there is this idea of monumentality—the muralists, for example. But there are many other, less investigated ephemeral artforms and activities, like the millions of private scenes women writers were describing back in the ‘40s, or the work of exiled people. Today, these heaps of memory and history remain invisible, but they are part of the environment—the way we form language, the way we form relationships—that are beyond these monumental monsters. diSONARE is an attempt to bring those layers of time, events, and international conversations between artists, poets, people who have migrated, closer to the surface. Questioning what identity means, within these terms, and the illegibility of that identity.

EG: Cuando estabas hablando, en mi mente oí códigos. Hay códigos que maybe uno entiende por el trabajo que uno está haciendo, that when you see it, you go, “¡Oh! Eso es.” En el dembow—ustedes ya saben cómo está el dembow ahora mismo por todo el mundo, pero salió de República Dominicana—hay algo que se llama los códigos, que vienen de todos los barrios diferentes. Por ejemplo, en Guachupita, Los Frailes, en Los Mina, todos tienen sus códigos específicos. Yo siento que es lo mismo con el arte. Hay códigos que tú quieres que la gente lea, y el que lo lea lo va a leer. Tú no tienes que decirle, “Mira en la esquinita de ahí abajo, hay un código para ti.”

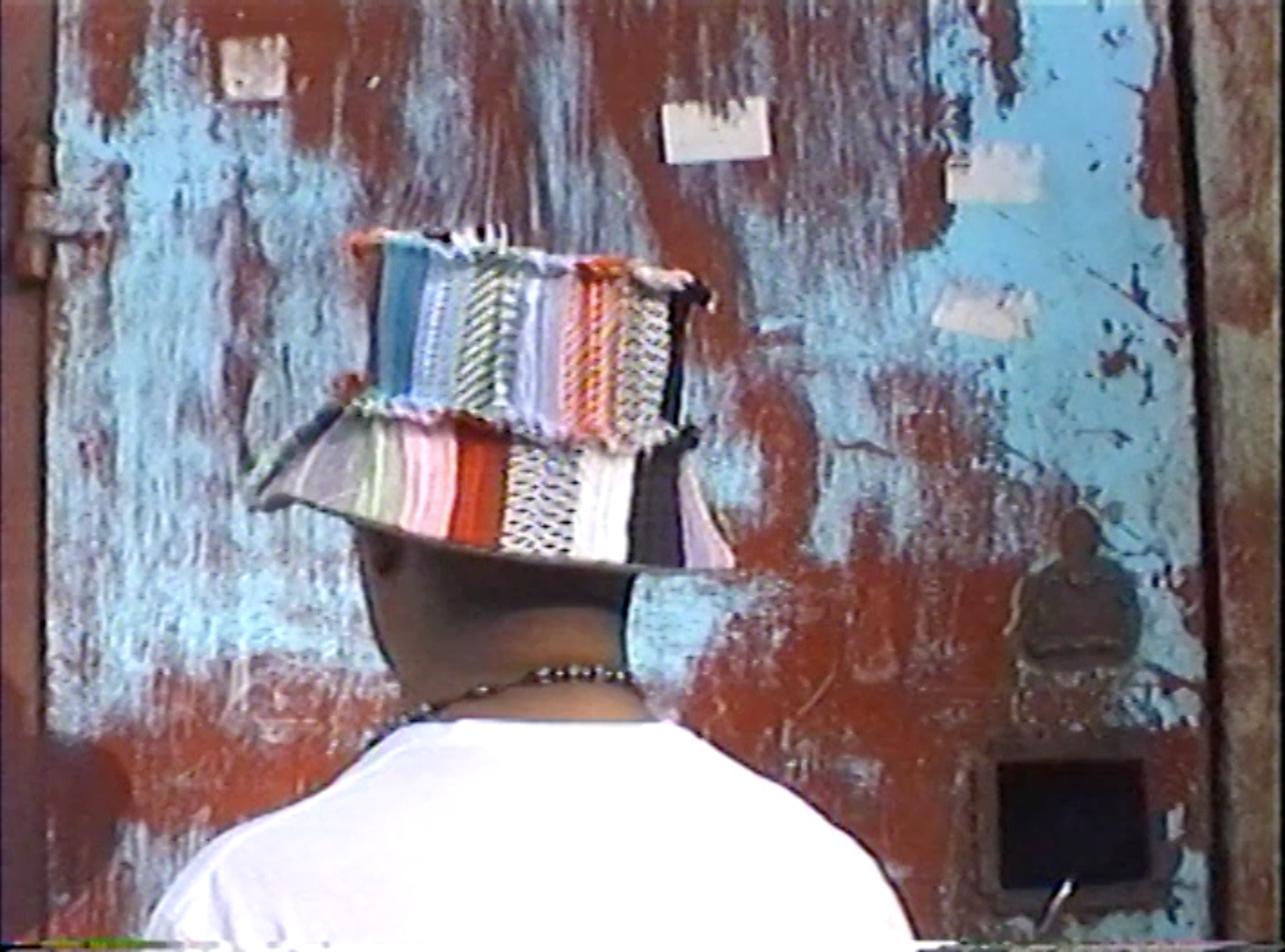

La cuestión de quién puede o no puede leer algo es una cosa que nosotros también estamos pensando. Cuando nosotros hacemos un gorro, el gorro es de alforzas, que son los pliegues de esas camisas bien tradicionales que se usan en Latinoamérica, como la chacabana o la guayabera. Pero nosotros hacemos un gorro. Cuando ese gorro sale de República Dominicana, con esa técnica que se usa aquí para hacer chacabanas, y se lo pone una persona en X sitio y no sabe lo que es una alforza o una chacabana, la pregunta es: ¿el código llegó adonde tuvo que llegar?

GCF: O sea que el código comunica aunque el wearer no sepa lo que está ocurriendo, primero; y segundo, que el código existe de una manera fuera del tiempo, porque el pasado no está encapsulado dentro del código, ni el futuro. And what we are doing in the present is this mistranslation of the thing which has been lost. The code is not a perfect index of the past, once it has been decontextualized, and it can’t simply be projected into the future. We are left to make an incomplete picture, essentially fuera de trapos.

EG: Exactamente. Pero también es una forma de exaltar las cosas que amamos. Y Lucía, dices que es lo mismo para ti. Es decir: “Wow, me encanta esto. ¿Cómo puedo coger un poquito de esto, y llevarlo y comunicarlo ahora?” Nosotros estábamos haciendo unos vestuarios para Tokischa que van a hacer en México. Ella nos dijo que quería algo que representara mucho la cultura mexicana. Y entonces pensamos, ¿Cómo nosotros podemos coger eso mismo y en ese mismo tiempo, incorporar algo de lo que estaba ocurriendo en República Dominicana? Si los jóvenes se estaban vistiendo de cierta manera en México, me imagino que aquí también había una frecuencia de eso.

LHG: Esos códigos llevan en tránsito miles y miles y miles de años. Se van cambiando y transmutando, y los códigos que tu avientas con una publicación, o una playera, no son leídos por todo el mundo, son leídos por algunas personas, que en turno a lo mejor los cambian. Es interesante, esta idea de la migración de una identidad. In diSONARE, we love unfinished products. Fragmented clues. Things don’t have to be finished, because they are never really finished anyway. We love things that are open, and that things can be forever repurposed and retranslated.

FE: Tiempo de Zafra collaborates with a lot of artists, as you mentioned. Can you talk a little more about how that works?

SB: Normally, we start with ideas, and then nurture the potential of those ideas. It’s always a collaboration, and we think about design ideas, color, and fabric, which dictate what the piece will become. We work with a lot of artists, not just in music. But because what we do is so unique, people come to us wanting something specific, and knowing that they can have a say in the unique piece that we are making for them.

FE: Because you work with a lot of discarded materials, there is also a collaboration with the original designers. That’s also a process where different people put a lot of effort into a design and the production of a garment, which is then thrown away; and you use these as base materials that also affect the idea of what you’re working with.

EG: It relates to how Lucía was talking about the unfinished. We find things that someone thought was finished as a garment, and then someone else thought was finished in a different way, in the sense that they decided to throw it out. And then, we take some of these things and give them another life.

FE: The cycle keeps going.

EG: Yes. We are very interested in unique fabrics, textures, etc., but we might find it en una chaqueta que es muy pequeña. Because we like the fabric, we save it, thinking that we can use it for a bigger piece. Sometimes, too, en la pulga, we will find something where we say, “Eso se ve bien ya. No hay que hacerle nada.” And in those cases, we don’t take it—que se lo lleve la doña, o cualquier amiguita de tal instead. The conversation is interesting: ¿Cuándo algo se termina? ¿cuando algo se comienza? y ¿cuánto tiene uno que decir en ese proceso? Maybe our intention to intervene in the piece was the motive from the beginning, for it to be repurposed into something. If we don’t intervene, nothing happens.

FE: Then it’s just piles. And the piles become harder and harder to sort through!

GCF: Tiempo de Zafra, as a kind of motto, takes into consideration the idea that there is abundance. That what we need for our use is already present, it is a way of looking at the world which is generous. On the other hand, the raw materials that you are using are themselves in this over-excessive state. No matter what, you couldn’t use all of this discarded fabric that you encounter. There’s an interesting tension between the impossible quantities of material in relation to the kind of local knowledge and information that you talk about being erased, and what it means to take certain kinds of actions to mediate between these two.

LHG: In relation to the idea of interventions, I was thinking about the various kinds of projects we receive in diSONARE through our open calls. Sometimes we get proposals for a project that has been thought through very carefully and is presented as a finished work, but we are more interested in the process: how was it conceived? What came before the work itself? We might instead say, “we want to publish this part of your research, perhaps sketches or notes.” We try to curate a process-based approach to ideas. We are also sometimes very cryptic. One of the artists we have worked a lot with [is] Christopher Rey Pérez, que también es poeta y editor. We made a triptych of his work “Anábasis en la Ciudad de México,” an experimental derive exploring the city and its margins, the parallels between narration and walking. We included three different pieces of the whole investigation in three issues of the journal, so the meaning is scattered across the issues.

Another artist, Daniel Aguilar Ruvalcaba, made a work dealing with Mexican bills. En el billete de doscientos pesos está el poeta Nezahualcóyotl, and on the 100 peso bill is Sor Juana. So we published the serial number of each bill as a form of poetry. Then, another artist, Marcia Santos, read the serial numbers aloud during an improvisational performance. We take things from here and there and repurpose them. We try to think of editing as a kind of radical translation of meaning and language. We try to think of words and language as “raw material,” to reference the term Edgar used.

EG: You see what I’m saying—the whole idea of independent publishing is so much of this process and I’m pretty sure en toda Latinoamérica es así. Porque lo que pasa es [que] cuando el gobierno no está haciendo lo que tiene que hacer, la gente lo va hacer igual.

SB: La gente busca los recursos…

EG: Hay recursos que son información, dinero, conexiones, creatividad. Y hay otros recursos, como decir “lo voy a hacer como sea.” Mucha gente no tiene la iniciativa de hacer las cosas porque necesitan que todo esté perfecto.

FE: Or depending mucho en las institutions y te terminas muriendo de hambre, actually Lucía te iba a preguntar sobre ese project Rizoma que haces con Anne Waldman for women’s prisons, where you do performances and poetry workshops. In a way, this is an initiative that you brought there because no one else was going to do it…right?

LHG: ¡Sí! Pues, yo quería colaborar y trabajar en cárceles de mujeres. I started performing randomly and I don’t know how it started but I ended up on a stage reading poetry and then I started meeting all these musicians in Mexico City. In my art practice, I don’t see performance as my main practice but as a sort of somatic therapy. I felt how it transformed my process as an artist and then I thought, why don’t we bring this methodology of improvisation and experimental poetry into women’s prisons? I had already participated in other prison workshops and I had established a relationship with some of the women. So this started in 2019 and it has been a very generative, nourishing and unexpected collaboration. It’s like what Tiempo de Zafra was saying, there is an ethos that is vibrant, pulsating in Latin America because there are many relational entry points between different groups that have to do with a multiplicity of syncretic histories. We (Rizoma, a collective of artists, musicians and poets) began by connecting the performance workshops to the Danza Conchera. Inside the prison of Santiaguito de Almoloya de Juárez, about 35 women are part of a dance group of Concheras, a ritual dance that has indigenous roots and is linked to both religious celebrations and shamanic practices. I was fascinated by how ritual and dance were such a strong somatic and devotional support expressed in the body and in community organization. So we were connecting this idea of ritual and dance to performance and poetry. So this is one of the other tentacles of diSONARE, and now we are working on a book of the women’s poems. Another thing I wanted to say was we have another friend in independent publishing that has a publication called “Made in Chinga” instead of “Made in China” because in Mexico ¡todo se hace en Chinga! Todo es…. ¡amarra esto rápido!

FE: ¿Qué es chinga? ¿Chinga es rápido?

LHG: Si, made in chinga es como… Made as fast as fuck! So it’s playing with that idea of “Made in China,” the whole thing is about how things made in Mexico are solved in a creative way with what is available in that specific moment.

EG: Aquí hay muchas cosas así. We pick up a lot of things and scan them… it’s kind of like the visual conversation of what the landscape is, so people understand where things are coming from. How chaotic, but how beautiful and how informal and magical the space we live in [is].

diSONARE is born out of the concept of dissonance, referencing the complexities that feed art & writing in their diverse genres and practices. diSONARE is an experimental editorial platform directed by Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola and Diego Gerard Morrison. We focus on hybrid art processes in the intersection between poetry and art, as well as translations, fiction and criticism. We publish an annual bilingual journal, organize readings and performances in Mexico and abroad, and develop various projects related to sound, performance, independent publishing, radio and activism. diSONARE is interested in building cross-cultural collaborations and promoting alternative ways of thinking about publishing as an experimental catalyst.

Tiempo de ZAFRA is an artist collective and fashion design studio, launched in 2017 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. A common term in the Caribbean, ZAFRA refers to the early autumn late summer harvest, a time of abundance. TDZ imagines the possibilities around excess and waste in a capitalist dynamic.

Precog is an annually published independent magazine that explores science, technology, techno plastics, cyberculture and feminism.

IG: precogmag

Website: https://precogmag.xyz/

—

Gaby Collins-Fernandez is an artist living and working in New York City. She holds degrees from Dartmouth College (B.A.) and the Yale School of Art (M.F.A., Painting/Printmaking). Her work has been shown in the US and internationally, including institutionally at the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama and el Museo del Barrio, NY; and in a solo exhibition at anonymous gallery. Her work has been discussed in publications such as The Brooklyn Rail and artcritical, and on the video interview series, Gorky's Granddaughter. She is a recipient of residencies at Yaddo (Saratoga Springs, NY), The Marble House Project (Dorset, VT), and a 2013 Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Art Award. Collins-Fernandez is also a writer whose texts have appeared in Cultured Magazine, The Miami Rail, and The Brooklyn Rail. She is a founder and publisher of Precog Magazine.

Florencia Escudero's sculptures include soft and handmade components printed with digitally-rendered imagery. Feminist theory, cyberculture, and an embrace of various techniques such as digital photo collage, hand sewing, and silk-screening place each sculpture in the realm of both the machine-made and the handmade. Escudero received an MFA in Sculpture from the Yale University School of Art in 2012. She lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, and is one of the founders of Precog Magazine.

Her works have been exhibited at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York, NY, and Petzel Gallery, New York, NY, among other venues. Works by Escudero have been discussed in Editorial Magazine, Aether Magazine, The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, The American Reader, Cultured Magazine, and the Brooklyn Rail. She was a 2016 year-long Artist in Residence at the Loisaida Center, New York, NY, and has also completed residencies at Art Farm, Marquette, NE, and Pilchuck Glass School, Seattle, WA.

Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola (Mexico City, 1987) is an artist, experimental poet and editor whose work explores the materiality of language, sound ecology, elements of chance, archive and memory. She is the publisher and co-editor of diSONARE.

Kellie Konapelsky is a creative director that has worked primarily within the cultural sector. She has over ten years of experience and specializes in art direction, publishing, and exhibition design. She sees her practice as a collaborative process that is multidisciplinary by working alongside photographers, illustrators, filmmakers, writers, and architects.

Diego Gerard Morrison is a writer and translator working in the intersections between appropriation, plagiarism and co-writing. He is the author of the play The Wait/La Espera, and the novel Myth of Pterygium. He is the editor and co-founder of diSONARE.