Adopting Performance: A Conversation with Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez

In the work of Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez, the challenge of how to reimagine physical spaces alongside the presence of their body’s own physical and generational history is interwoven with their identity as a transnational adoptee. I first encountered them in conversation for a curatorial project of theirs titled Se Aculillo?, co-curated by Kat Chavez, in Providence, Rhode Island. The project contested the fear from art spaces and institutions to work beyond tokenization and mass grouping, as well as the dismissal of identities and bodies, ideas challenged in Lundberg Torres Sánchez’ various works.

As a domestic adoptee, ideas of reclamation and the search for ancestry and generational history place me in a personal state of limbo, a space that informs the way I navigate my work in relation to art. Conversations around discovering, deconstructing and dismantling ancestry are dissected through the lens of our experiences as adoptees. There becomes a method of work in how we self-educate, while also educating those within, connected to or outside the community of Adopted and Fostered Peoples, a role Lundberg Torres Sánchez has taken on in their work surrounding Adoption and Foster Care Abolition.

In our conversations, I became drawn to how they engage spaces with histories and ancestry using their body as material and vehicle. In TO THE BONE (2017), Lundberg Torres Sánchez engages in the laborious task of sanding down the surface a piece of clapboard siding, painted “White Core,” and slowly excavates to reveal the coat of “Nearly Brown” paint, an act that mirrors the labor of decolonization. Labor through the body is also seen in their earlier work Parachute, (circa 1988-2006) (2015), where Lundberg Torres Sánchez engages with a parachute created from newspaper archives given to them by their mother, compiled under the terms “Colombia” and “Adoption.” The performance examines the term inheritance and what it carries, which as an adoptee can include the information of your personal history and first family given to you at the discretion of your adopted family.

In a deeper conversation, we spoke of their personal work as an artist and the work of Adopted and Fostered artists to dismantle and decipher these ideas within our personal context. In these short excerpts, Lundberg Torres Sánchez also highlights their work with Adoption and Foster Care abolition, how their adoptee identity influences their practice, and their work as a performance artist.

MOS: The idea of space is something I see in your work, your body as space, but also as a conceptual space. How is this idea of space in relation to boundaries and of the idea of forced removal something you play with in your performance work?

BLTS: Trying to place my body where my question is a phrase that comes up for me sometimes. In that way, I'm really trying to create spaces that are plural, that invite questioning or investigation, places that I make some guesses about that I’m really hopeful will be live enough to push me into directions I didn't plan for or perceive. I think early on in my performance work, I had to start in a very me-centered identitarian space, because that didn't feel available to me in theatre. I was receiving a lot of information that suggested to me that there was some kind of universal story to tap into, which I think a lot of artists face when they are being trained in a certain way, so I think I just had to break that down and build some comfortability in facing myself and my art, which looked like a lot of explorations of adoption and explorations of my relationships to states. I think an adoptee sometimes, especially a transnationally adopted person, feels some kind of longing towards some kind of place that they don't maybe know or haven't experienced and that gets expressed most often in terms of nationalism because it’s available. I think I had to really deal with some questions about experiences that I know are viewed in a particular way by mainstream cultures.

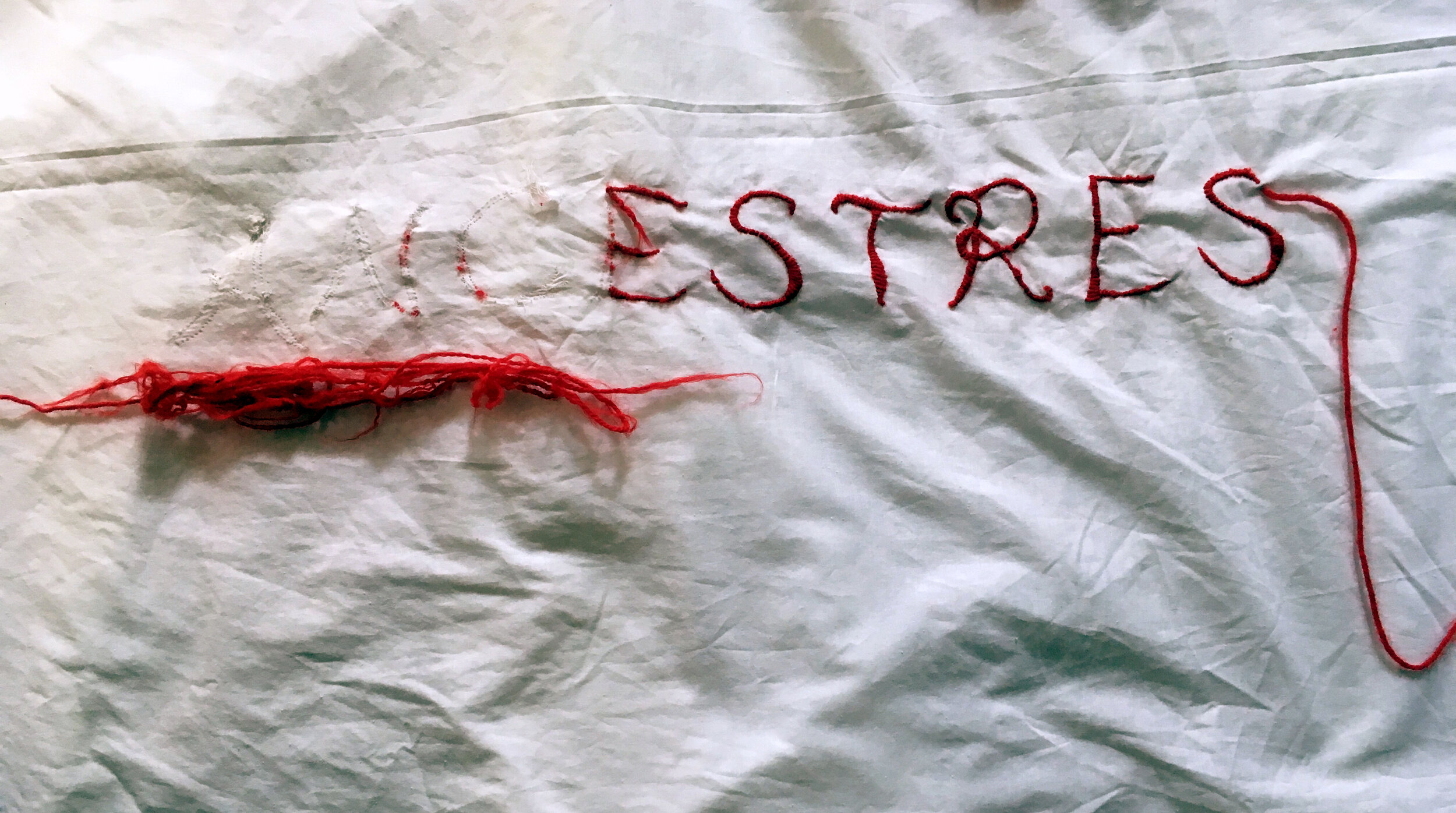

MOS: I want to touch upon your use of craft within your work. You use a lot of ideas of embroidery and using textile within these ideas that you’re piecing together. In specifically talking about your piece Ancestres (2019) and the use of thread and fabric, how do these materials tie together with these ideas that you speak about?

BLTS: Ancestres (2019) came from a performance experiment, an impulse that I was asked to try to make something in five minutes. I was working on embroidery and I was feeling what you had brought up earlier about the commodification of ancestry and ancestors. I had to decide, how am I going to figure ancestors, so I chose Spanish and I chose gender neutralized Spanish. As a queer person who wants to investigate the queering and gender neutralizing of this language that I'm supposed to have a connection to but is also colonial, that part comes from what I can know, from my relationship to language, to to my body, to queerness. Am I talking in Spanish to antepasades? Or am I talking to ancestres, the different [ones] between generations that are near to me, and generations that are buried in history? I think what I’m hungry for is the root of the root. The other thing that was so apparent to me was this word [ancestres] has to be created with one unbroken thread because that’s a fantasy I have as an adopted person. In this process, I wanted to make this cumbia skirt to dress myself in something that is available to me. My cultural references sometimes feel scarce to me, but I can like latch on to cumbia because it’s something that feels available because of its spread. My heart reaches for the dress, my heart reaches for an idea of who came before me that I still have so many questions about, this process of weaving as both how am I trying to return to that story but then also in the performance in picking it out little by little and trying to unravel it. I see the holes that are still there, I see the impression of what the embroidery was before, I have the memory of doing it all over again. Another iteration of going into the thread, going into the story or going into the space of trying to understand again and then undoing it again. Thinking about it was really healing to me, to think about the ways in which what I cannot perceive is still there. The other point of that triangle between my question about ancestry, the dress or this cumbia skirt and the form of that movement was to bring in one of my most contemporary, superficial ways of grounding myself as somebody who knew that they were Colombian growing up, which was to put Shakira in there too. My dance and movement vacillated between when cumbia was playing on my tape recorder, but I stopped to undo the ancestor word while listening to Underneath Your Clothes, which was something that I was listening to as a young person. I'm very interested in how you can bring a reference like that that has a personal meaning that other people don't really need to know or perceive. Every lyric felt a significance to this quest for ancestor and the relationship with ancestor, "you are a song/written by the hand of god" or Shakira's references to territory and the land and what is uncovered, and just wanting to have longing, desire and sit in desire and for intimacy with ancestors as such a huge part of the collage that is brought into that performance.

MOS: I know personally as someone who is domestically adopted that I have a certain proximity, but at the same time, there’s this distance in grasping at identity and specifically thinking about concepts of ancestry. I see personally, with the continuation of speaking of identity especially within Latinx art, the idea of ancestry constantly comes up. The whole idea of ancestry has become almost commercialized in some way with people hunting for DNA kits and learning about their "true" ancestry but also realizing the sort of privilege in that and how it’s such a commodity. What are your thoughts on the idea of ancestry, how you sort of play with that and come to terms with that in terms of adoption, the child welfare complex and the foster care system?

BLTS: My immediate thoughts go towards this predicament of DNA testing within the perception of scarcity around identity for adopted people who are experiencing situations that touch on many other people’s lived experiences, like forced removal, forced migration, being cut off from culture, from land, certain kinds of re-education, dynamics of assimilation. For transnationally adopted people, adoption is an immigration story. In indigeneity, I think there’s a lot of ripe, messy and complex questioning that comes from an adoptee space about understanding relationship to land and kin from lands that we've been removed from, particularly in my case, and in many other peoples context where indigeneity is criminalized and submerged by a national culture. Adoptees in reunion with their first family are even facing further blocks to knowing self because of the way that information has been submerged both by nation, by culture and by your direct family. To bring that back around to performance, I think that’s why knowing and the body is so important to me, trying to understand what it is that I know in a sense without relying on some European shit like archives and data is really important to me, and sometimes that looks like sensing the body, sometimes it looks like figuring something outside of myself. All these things I've mentioned about migration or forced migration, these situations that spiral out of adoption, I think connect to other identity spaces certainly, but also just lived experiences of people on this earth.

MOS: I think people see adoption and foster care in such a separate light when it’s connected to white supremacy and capitalism. Adoption is an industry of purchasing children as a product. I think a lot about the term "investment syndrome" and feeling like you were a paid-for product and how that affects thoughts on being an adoptee. I want to give you space to comment and speak towards abolition in terms of adoption and foster care.

BLTS: Right now, in returning to self and also connecting self to wider systems and experiences of others through considering adoption and foster care, I am so fortunate to be in community with a small group of people I met in the frame of an academic conference called the Alliance and Study of Adoption and Culture (ASAC) in 2018 in Oakland. With those comrades that I met there who have many different kinds of experiences with adoption and foster care, transracially, transnationally and adoption situations that were compelled by the 1970s Baby Scoop. All of our experiences certainly point to these systems that you’re naming, of capitalism, of white supremacy, and, I think that’s where my awareness was most early on in my politicized adoptee identity: considering whiteness and considering class and capitalism. I think you’re right to name it as a for profit industry that requires children in order to remain profitable and there’s a flow of children from the Global South to the Global North. I think as I continue to be in relationship with this struggle and to find more politicized adoptees and to find other spaces of connection that are opening up, we know that adoption and foster care disproportionately impact Black and Brown people, in particular Black and Indigenous people, and so I think it’s becoming more and more clear and apparent to me the systems like prisons and borders and the death penalty, are things that can cause a lot of harm in kinship, family members being removed from familial contexts, separation, short term and long term, that are injurious to people.

Maya Ortiz Saucedo (b. 1996, Chicago, IL) is a domestic adoptee artist and researcher based in Brooklyn, NY. They have shown their work domestically in Providence, RI, Chicago, Illinois and NYC and internationally in Singapore.

Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sanchez (b. 1987, Bogotá) is a queer, transnational adoptee artist, educator and curator, based in Providence, RI. Lundberg Torres-Sanchez has shown their work domestically at the Queens Museum (New York), RISD Museum (Providence, RI), the Knockdown Center (New York) and internationally in Mexico City, Montreal, Sao Paolo and more. They have worked as a co-curator with artist Kat Chavez on the series Se Aculillo? and were the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts 2017 and 2018 Merit Fellow in New Genres and Film & Video.