Afrofutur1st Garçon: From Material to Matter

On the third floor of Terminal 5, a historic Manhattan venue for the New York Ballroom community, Afrofutur1st Garçon prepares to walk in the GNC (gender nonconforming) Runway category of The Latex Ball, the oldest annual event of the House/Ballroom culture. While still in casual clothes and colorful makeup, Afro leans toward Samuel Paulish, their partner and collaborator, who is decorating a banner that will serve as Afro’s background for their first walk. They look nervous and try to concentrate on Paulish’s creation. Resting against the wall are a few pieces of Afro’s luggage but no trace of the outfit they will present that night.

Community members, possibly also feeling pre-event jitters, fill the space. Portable changing rooms line the hall. Beneath them are piles of clothes on tables and suitcases on the floor. Under a dim light, clusters of people bustle around helping each other get dressed or apply makeup.

The third floor of The Latex Ball becomes a giant dressing room, moving at the pulsating pace of vogue beats that blare from the speakers. The commentators’ voices emanate from the first floor, where performers battle each other for a grand prize. The tension is palpable and the stakes are high.

Afro walks at 1 a.m. and wins the grand prize, earning $1,000 for their participation. Their look transformed their medium-sized figure into a monumental moving garden. They wore a floating seven-foot horizontal green skirt dripping with florals and a tall headpiece from which purple flowers sprouted. In this look, they walked confidently, swaying and maneuvering their hips to make their skirt swing and twirl with grace and precision. Dominating the runway while combining poses and branch-like arm movements, their walk was both grounded and ethereal. Afro’s uncanny look was as if a burlesque Marie Antoinette had reincarnated as a larger-than-life forest nymph.

Afro’s creativity is a result of their upbringing. With humble origins in Sergipe—the smallest state of Brazil, located in the northeast part of the country—Johnatan Rezende grew up an only child. Raised in a favela, they quickly learned to turn shortage into possibility through a creative mind: “I always had to find ways to entertain myself. That means transforming objects and materials into toys. I come from a place where there are not many resources. So if I want to have something, be something, I have to find a way to make it or find a way to transform things.”

The same child who made kites out of fallen coconut tree leaves and plastic is now gathering discarded items from NYC's streets and creating jaw-dropping effects in the New York Ballroom scene. Repurposing materials like mannequins and cardboard, Afro works with found materials to produce spectacular effects and outfits that have earned them multiple grand prizes and the awards of Bizarre and GNC of the year. Their craftsmanship and unconventional thinking have also brought them recognition in the balls, allowing them visibility and, in 2023, an invitation to join the International Legendary House of Comme des Garçons, who they now represent in the categories Bizarre, GNC Fashion, and GNC Runway.

Throughout Afro’s journey, resourcefulness has been the backbone of their creative process and their secret weapon to navigate and overcome challenges in the New York Ballroom scene. Black and brown trans and gender nonconforming folks created this culture in the ‘60s as a way to transform oppression and marginalization in networks of support, community, and joy. The Ballroom culture continues to be a space that celebrates sexual and gender diversity. Still, the growth and visibility it has achieved over the decades have turned it into a scene that juggles a complex balance between commercial and economic success and its community roots. The commercial side of Ballroom culture shows up in the ball, the main competitive event. Performers make financial investments to participate in categories where they compete for prizes ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars. Houses have to pay anywhere from $250 to $2,000 to secure a spot in the event. This reality can work in opposition to Ballroom’s goals by generating exclusion of members of the community with limited buying power.

In this complex scenario, Afro and other Latinx artists walk and battle for a grand prize but also for visibility and belonging in a scene and a city that often shuns them. Afro’s foray into Ballroom Culture started in 2016 when they set foot in New York for the first time. However, their “Ballroom energy” emerged as a teenager when transitioning from military school to university. The restraint and tidiness of their early education gave way to a burst of individuality and a defiant nature. Disobeying their mother’s wishes to seek a conventional and financially stable profession, they instead became the first person in their family to pursue a career in the arts, studying dance, acrobatics, music, and theater. In 2016, Afro won a national dance competition that awarded them a scholarship to do a summer intensive program in New York at the Joffrey Ballet School.

During this time, Afro met Michael Lubbers, known as Michael Alpha Omega in the Ballroom scene, who taught them to vogue and took them to their first ball. At first, balls didn’t impress them. “People are just slamming their backs on the floor,” they say. “This is not for me.” However, in 2019, they attended The Latex Ball to see Lubbers walk. This time, they dressed up, putting together an expensive-looking, Versace-inspired outfit with leather pants, a chic black-and-yellow button-down shirt, and a big golden belt bought from a thrift store. They fit in. Suddenly, people were saying, “Are you in a house? Are you walking? You look fab!” Afro felt seen.

Later that night, they witnessed the Bizarre category for the first time “I saw myself,” they say. “This is performance art. This is avant-garde. This is forward and is weird. I want to know more about Ballroom and see where I can go with it.”

Bizarre transcends the traditional expressions of male and female figures to enter the genderless terrain of the indeterminate. It rewards thinking outside the box, beyond the limits of what defines a body. This flexibility invites performers to envision and execute special effects that play with size, dimension, and materiality. The body becomes a 3D canvas no longer limited by the flesh, a fact that invites performers to construct a more-than-human physicality that goes beyond the performer’s body to include materials that shift their shape and proportions. Bizarre requires fashion and makeup skills, arts, design, and even engineering, as it can incorporate knowledge of structure-building to transform the performers’ bodies into alternative shapes and out-of-world beings.

A few months after Afro attended The Latex Ball, the COVID-19 pandemic changed the world; Afro had to return home. Confronted with a climate of fear among the LGBTQ+ community in a time of uncertainty and vulnerability, a reality heightened by Brazil’s then-president Jair Bolsonaro’s anti LGBTQ+ rhetoric and practice of dismantling existing support to queer communities, Afro felt unsafe and unwelcome in their country.

Isolated by the lack of queer spaces and pushed once again to create something out of nothing, Afro launched Lady Bixa, a production company that served as a platform to develop safe queer spaces. It started by creating the first ball and a three-month workshop introducing the community to Ballroom's history and categories. And in this way, progressively, Ballroom culture in Sergipe was born.

Ballroom Culture dates back to at least 2015 in other Brazilian cities—Brasilia, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro. However, introducing the culture to their hometown was not easy. Sergipe is a society keen on preserving traditions; thus, it was skeptical about welcoming an international culture with English as its language. To Afro, this was a challenge to show others how Ballroom could be relevant in their context. “How do we take this culture that’s very important for the queer community historically and make it ours?” they say.

Staying true to their local needs and finding a balance with tradition, Sergipe adapted Ballroom to incorporate aspects of Brazilian culture. Performance categories would open to include Afro-Brazilian dance forms and rhythms such as samba, capoeira or passinho (Brazilian street dance style) allowing them to bring “their own flavor” to the ball. When necessary, its participants translated language to Portuguese to attend to what spoke to the local queer community, for instance, transforming realness to “realidade” or face to “rosto.”

For Afro, this process revealed that Ballroom is relevant wherever it arrives because of its three pillars: the houses, the balls, and the community. Ballroom protects and celebrates Black, brown, and LGBTQ+ people. As a community that faces prejudices, discrimination, and violence in a country where its former president stated publicly in 2011 that he “would be incapable of loving a homosexual son,” houses provide a family to those who have been denied one. Balls bring people together to celebrate who they are and to walk in ways restricted to them in everyday life, becoming world-making spaces where dreams can come true. “Like, tonight,” Afro says, “I am something that I cannot be in the daylight.”

Afro returned to New York in 2021 after founding the Pioneer Kiki Casa DiBarro and becoming the mother of the first Ballroom house in Sergipe. They physically left the space but remained as a mother, emotionally and financially supporting their house and children. “I want them to be also part of my life and my experience here,” they say. “I want them to understand that if I am here, there is a place for them in case they want to come. In our culture, we give more value to the things outside; we don't value ourselves.” This goal keeps Afro connected to their family with the wish of providing them with a reference that engenders validation. Every win, every achievement is a way of showing them it is possible.

Despite their pioneering role in Ballroom Sergipe, they had to start over again in New York. Out of their local scene, they became a 007, a free agent who doesn’t belong to a house, in the mainstream scene. As a Black, nonbinary, and immigrant artist coming from one of the most impoverished states of Brazil, their experience navigating the Ballroom scene is marked by the lack of resources and accessibility to walk in balls. From the start, Afro battled for visibility in and outside the balls.

Balls are platforms for recognition, where walking is the medium that can catapult someone out of anonymity. Walking entails financial, emotional, and physical labor that is hard to endure when participating in the scene as 007. Ballroom’s house system is essential in providing performers with an emotional and material structure to navigate the scene. However, gaining membership in a house entails a long process where performers must prove themselves valuable to the house’s mission of winning balls and strengthening their legacy. This is not easy to achieve without the means to walk, which produces a hamster-wheel situation where several Latinx and immigrant members find themselves trapped. Some never make it. “I am one of the few Brazilians that I know in New York that walk as part of a mainstream house,” they say. “I would say one of two or three.”

To enter the House of Comme des Garçons, those in the culture had to see Afro first. This demanded consistency and hard work as a free agent. “I was going to OTA, a weekly ball that happens every Monday, and I was always there and walking,” they say. “And Lana Garçon, my mother, came to me and asked me, ‘Want to come to the Garçon practice?’” After this, they went to every practice.

When the highest members of the house interviewed them in the last stage of the admission process, they all remembered Afro from a previous ball. “I made a recreation of the album cover of ‘Cunty,’ which is one of the big tracks in Ballroom, made by Kevin Aviance,” they say. “When I came out with that cover recreation, everyone just gagged because the recreation was perfect. I put the cover on my back, holding the same pose as Kevin, like with the bald head and everything. Kevin was a judge that day. When they saw me, they stood up and started clapping, almost crying.”

These instances of performing and standing out by their perseverance and ability to draw attention allowed Afro to become part of the house, where they would finally step into a bigger spotlight.

As a Garçon, the stakes in walking are high, and Afro has to keep proving themself constantly. The highly competitive nature of Ballroom demands an immaculate level of production and performance in categories that showcase the performer’s body, gender expression, fashion, and artistic skills. The Bizarre category demands external materials and props to portray a creative vision, making it an expensive category in which to walk. Nevertheless, its over-the-top nature makes it the perfect category for a creative and resourceful mind such as Afro, who understands their performance as “turning trash into treasure.”

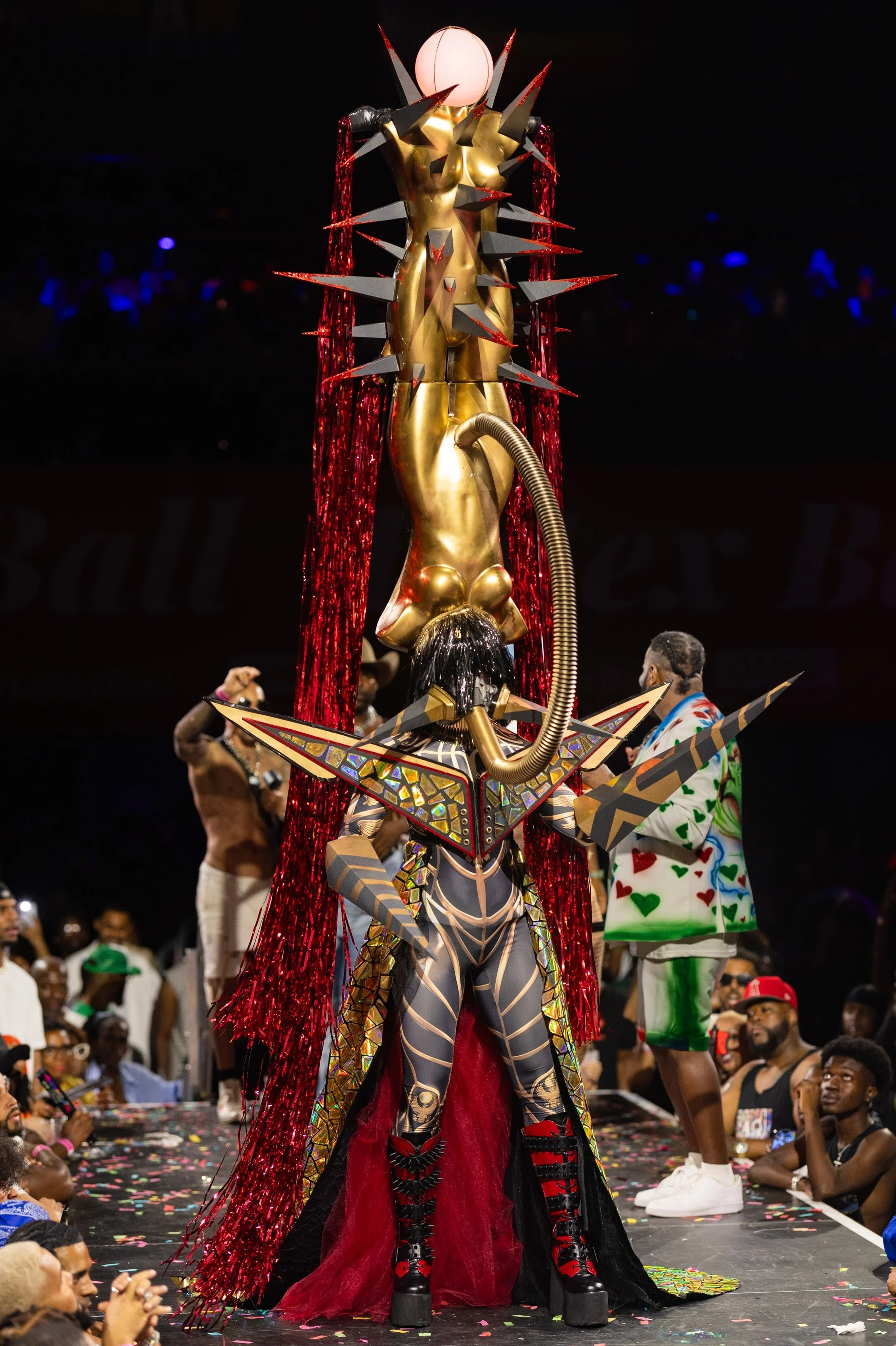

For the 2024 Latex Ball, Afro created their effects out of two mannequins—one on top of the other—that they found in the streets. “I want to go big, but I want to go vertically,” they say. “I want to bring Afrofuturism . . . I want to put two bodies on top of my head, and I want them to wonder, ‘How did they do that?’” The rest of the outfit consisted of cardboard, duct tape, and other upcycled materials, amounting to a $300 effects budget that won the Bizarre grand prize of $1,000, putting Afro’s geniality on the New York culture’s radar.

Afro’s effect drew from Afrofuturism, a concept and movement that brings Black experience into the future. Understanding Afrofuturism as “technology from the ancestors,” Afro sought to construct an effect that paid homage to their name and The Latex Ball’s historic mission of raising awareness about the HIV crisis. Afro’s view of an apocalyptic future included a 13-feet-tall totem-like figure, dressed in black, red, and golden colors, ornamented with blood-drenched, pyramid-shaped spikes. Their imposing height and geometrically shaped body distinguished them from competitors on the runway. Afro walked intentionally; as they moved, they projected the image of a futuristic soldier walking ceremonially, with slow, angular movements. They stretched and bent their arms, which doubled as weapons, while red tinsel descended from the top of their prosthetic heads resembling spilled blood.

Their effects were part of the Legendary Looks exhibition: The Art of Effects Design in House Ballroom¹ at Westchester Gallery, which presented a selection of the top effects and looks displayed in the Ballroom scene’s history.

Beyond the power to move audiences with their story-driven effects, Afro has the ability to make something out of what others might deem as nothing. It took them more than a month to develop the effects, including designing, assembling, painting, sewing, and embellishing. With the help of Paulish and plenty of trial and error, they polished the look and made the structure wearable for a runway. Once ready, Afro had to rehearse, allowing them to become one with the artificial backbone that sustained the top of their “new” body.

Afro’s ability to navigate challenges through creativity and resourcefulness extends beyond artistic categories. When they arrived in New York and started to walk in balls, Afro was continuously getting chopped, contributing to their feeling of not fitting anywhere. “What was happening was about the presentation,” Afro says. “My drag was not feminine enough; my butch queen was not masculine enough, so I was always feeling uncomfortable.” Afro’s testimony illustrates the complex intersections of gender expression, identity, and sexuality within the Ballroom Culture. Through performance, this culture has historically built the possibility to enact and stretch gender categories, challenging the hegemonic expectation of correspondence between gender identity and expression. Nevertheless, Ballroom is not about undoing gender categories; whereas it allows playfulness and crossings between genders, it still remains binary.

Thus, Afro took on a new battle, fighting for space for nonbinary individuals. One way to do this was through advocacy for the opening of the GNC category in balls in New York. The GNC category had already opened in Florida in 2022 to give space to those members who needed to express gender differently on the runway. Even though the category came to fruition so gender nonconforming and nonbinay people could feel included, GNC is not an identity-centered category. GNC in mainstream ballroom, as the GNC Advocates² explain, “is a gender expression representing a non-traditional mixed gender appearance” that materializes in the combined use of masculine and feminine clothing and accessories. Outside Ballroom culture, gender nonconforming can be expressed in any way possible.

After learning about the GNC category, Afro immediately turned their initial feelings of exclusion and invisibility into action. They started advocating for this category in every ball they wanted to join. “I started talking to the producers, saying, ‘Hi, I do not identify with your categories. I want to walk,’” they say. “‘I am gender nonconforming, and I would appreciate it if you could have this category.’”

Afro received positive and negative answers until the big day arrived. After asking for inclusion in the fourth Annual BRTB TV Awards Ball 2024, they prepared to walk for the first time in the GNC Runway category. The theme was Black Power, and they constructed an outfit based on the Black Panthers. To make a statement for the GNC category, they wore the nonbinary flag as wings on their back. Afro soared across the runway and won their first grand prize in New York. Since that day, they have continued to champion the GNC category in balls, so more GNC people feel they have a place.

Back on the third floor of Terminal 5, Afro prepares to walk in the GNC Runway category of The Latex Ball. Standing nervously, Afro notices that Paulish is unsure about finishing their background banner due to the crowd of people assembling. They are in a corner of the busy entrance hall, a spacious, multi-purpose area where performers transition between the improvised dressing rooms and other floors, as well as gather to get ready for the ball.

Paulish is afraid to take up space. Afro, without hesitation, lays the banner on the floor and encourages him not to give up. Gradually, under the reassuring gaze of Afro, Paulish begins to attach the plastic flowers, one by one, outlining Afro’s name on a green neon fabric banner that will introduce Afro’s winning walk down the runway. Finding space to exist in New York can be challenging, especially for immigrants who often struggle with feelings of not fitting in. As a result, they tend to shrink themselves. Afro does the opposite “I will take as much space as I need because I must do this,” they say. “If you start something, you find a place to finish, because that is my life. That is how I returned to New York City and found ways to fit in. So I will take space because I have a mission to accomplish.”

¹ Legendary Looks exhibition: The Art of Effects Design in House Ballroom is one of a three-part exhibition series, coorganized by ArtsWestchester, City Lore, and Pioneer Works focusing on House Ballroom Culture Legacy. Icon International Mother Twiggy Pucci Garcon, Legendary NYC Mother Jonovia Chase Lanvin, and Icon Ballroom Hall of Famer Founder Michael Roberson Maison-Margiela curated the exhibition.

² From an FAQ About GNC in Ballroom: A message from GNC Advocates by Rikka Milan, Prince Hodge 007, Lisa West, Reanté St. Laurent.