“El Preso”: A Salsa Liberation Anthem at 50

Fifty years ago, Colombia’s first international hit—“El Preso” by Fruko y sus Tesos—was born. It remains a singular salsa anthem; a classic in a celebrated canon of modern Colombian music spanning pop-tropical stars Carlos Vives and Shakira to trap titans J. Balvin and Karol G. A closer view into the social and political context of “El Preso”—the prisoner—reveals a subtle departure from salsa’s “Big Bang” origin narratives of 1970s New York City.

Just beneath its hard-salsa rhythm and brassy crescendos is the true-to-life story of a Colombian man who served a 30-year sentence in a Canadian prison on drug-trafficking charges. Also in 1975—and in the same Colombian city, Medellín, where “El Preso” came to life in Discos Fuentes’s studios—a then-unknown petty criminal, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria, began smuggling North Colombian cannabis into South Florida waterways to later graduate into the world’s “King of Cocaine.” Meanwhile in Washington, D.C., in the demoralizing wake of Watergate and the Fall of Saigon, a select Senate committee, chaired by Sen. Frank Church, led a series of hearings to expose the national intelligence community’s sordid secrets to the U.S. public and wider world: evidence of covert histories in U.S.-led coups and human rights atrocities across the Cold War “battlezones” of the developing world.

“El Preso” articulated these shifting political realities for Latin Americans generally, and specifically for Colombians and Andean nationals, in an inspired contribution to a popular “salsa” genre rooted in the diasporic Afro-Caribbean mestizaje of Puerto Rico and Cuba. Over pianist Luis Fernando “Tomate” Mesa’s pounding keys, the band’s vocalist—a young Afro-Colombian soccer player-turned-singer, Wilson “Saoko” Manyoma—improvised his now-iconic opening declaration: “Hey, I’m speaking to you from prison!”

Álvaro Velásquez, a friend of the band and fellow musician, penned the lyrics for “El Preso” after visiting his friend, Gustavo Gómez, in a Toronto prison. Velásquez and his band, Los Graduados, were touring North America with a stop in Toronto where he’d recently learned of his friend’s detention. Reunited with Gómez, opposite an armor-plated window, Gómez detailed his isolated life in incarceration, gripped by unshakeable fear and desperation. On the six-hour flight home, Velásquez penned a dedicatory lament inspired by Gómez, styled as an existentialist riddle. “In the world I live in, there are always four corners. But from corner to corner, there’ll always be the same,” he wrote. “Everything is darkness.”

Gómez, it seemed, was part of a new generation of Latin Americans, mostly peasant farmers, caught in the headwinds of a North American law-enforcement apparatus waging a widening “war on drugs” rapidly reshaping hemispheric state relations. Years later, Escobar and his narco-capitalist mafiosos famously tangled with a host of spy agencies and armed militias from the U.S. and Colombian national security state in the war’s cresting—and bloodiest—moments.

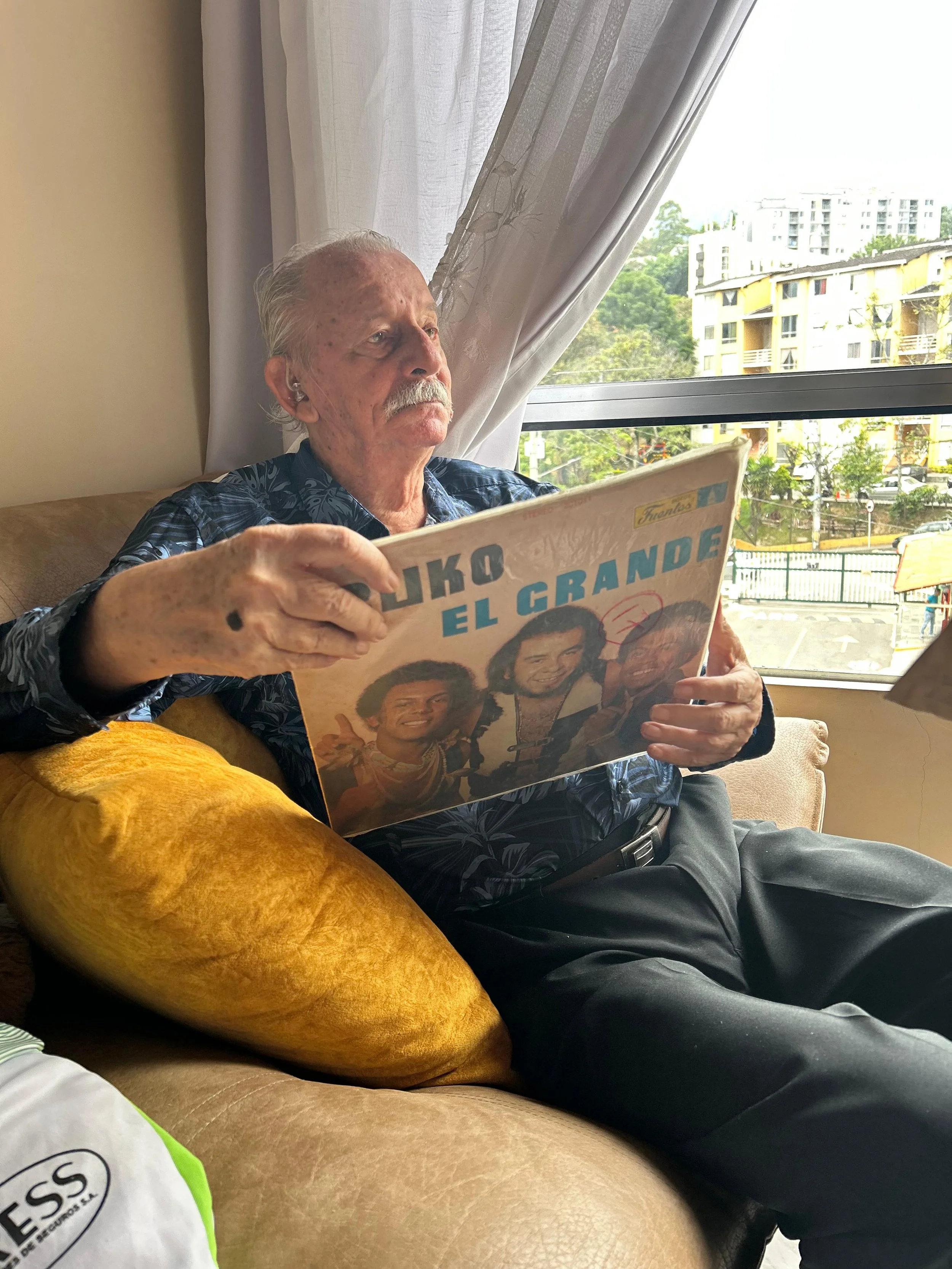

From his fourth-story apartment in Medellín, one of Discos Fuentes’ most famed producers and recording engineers, Mario “Pachanga” Rincón, remembered the making of Fruko y sus Tesos’s hit record half a century ago—a defining moment in an illustrious decades-spanning career in Colombian music production. “Álvaro came to Fuentes and showed us the song. I liked it; I knew it was good,” Rincón recalls. “We decided that this was something we needed to record.” He tapped Fuentes’s musical arranger, Luis Carlos Montoya, to compose a Fruko-style salsa melody. In the studio control room, Montoya added his vocals to the chorus as Rincón rolled tape on that fateful session. “Velásquez initially arranged the song in a vallenato style. It was something he wanted to record for Codiscos (Records) since he was signed to that label at the time,” Rincón adds. “But Codiscos didn’t want it. So he decided to bring it to Fuentes to see what we could do with it.”

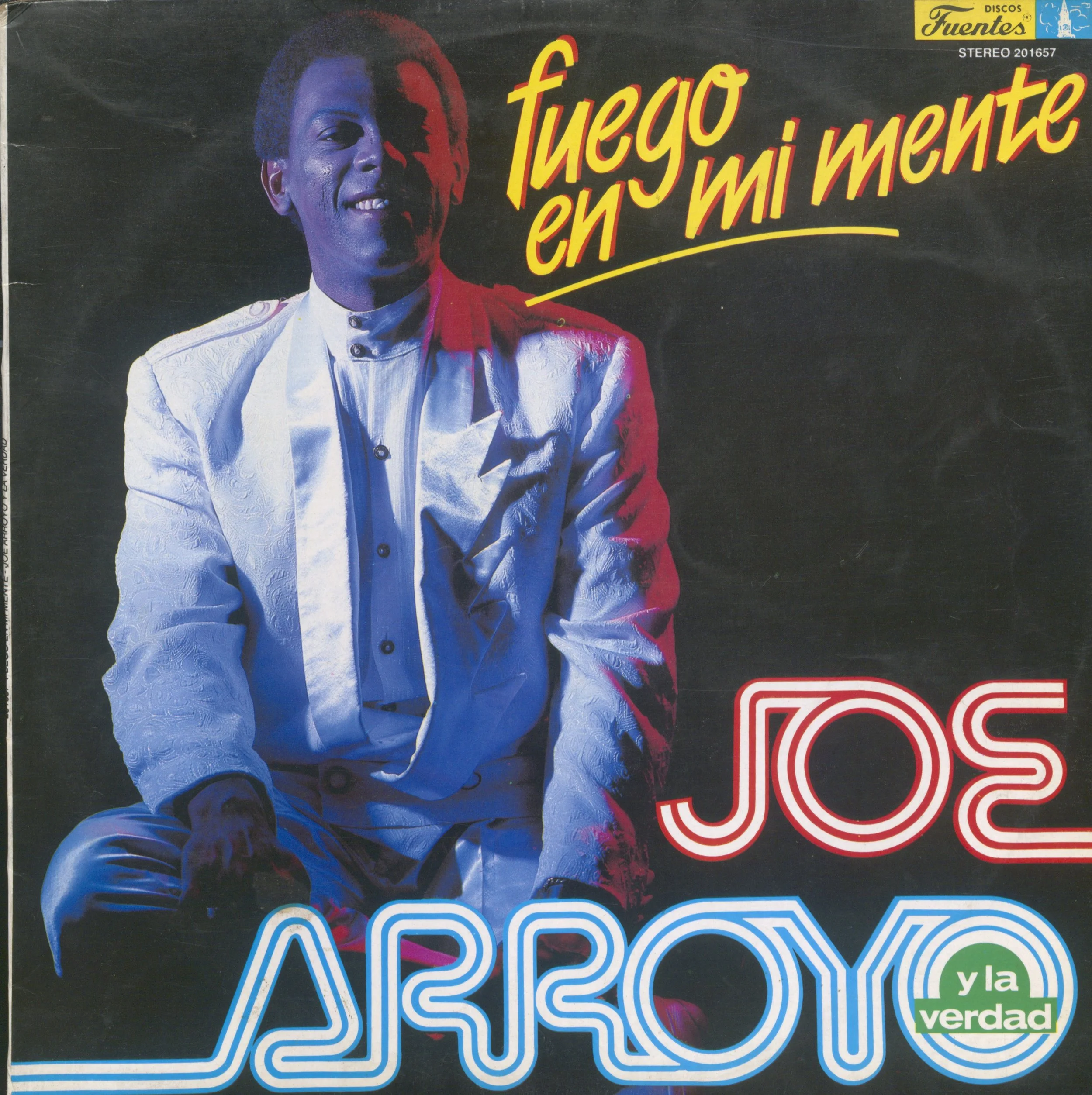

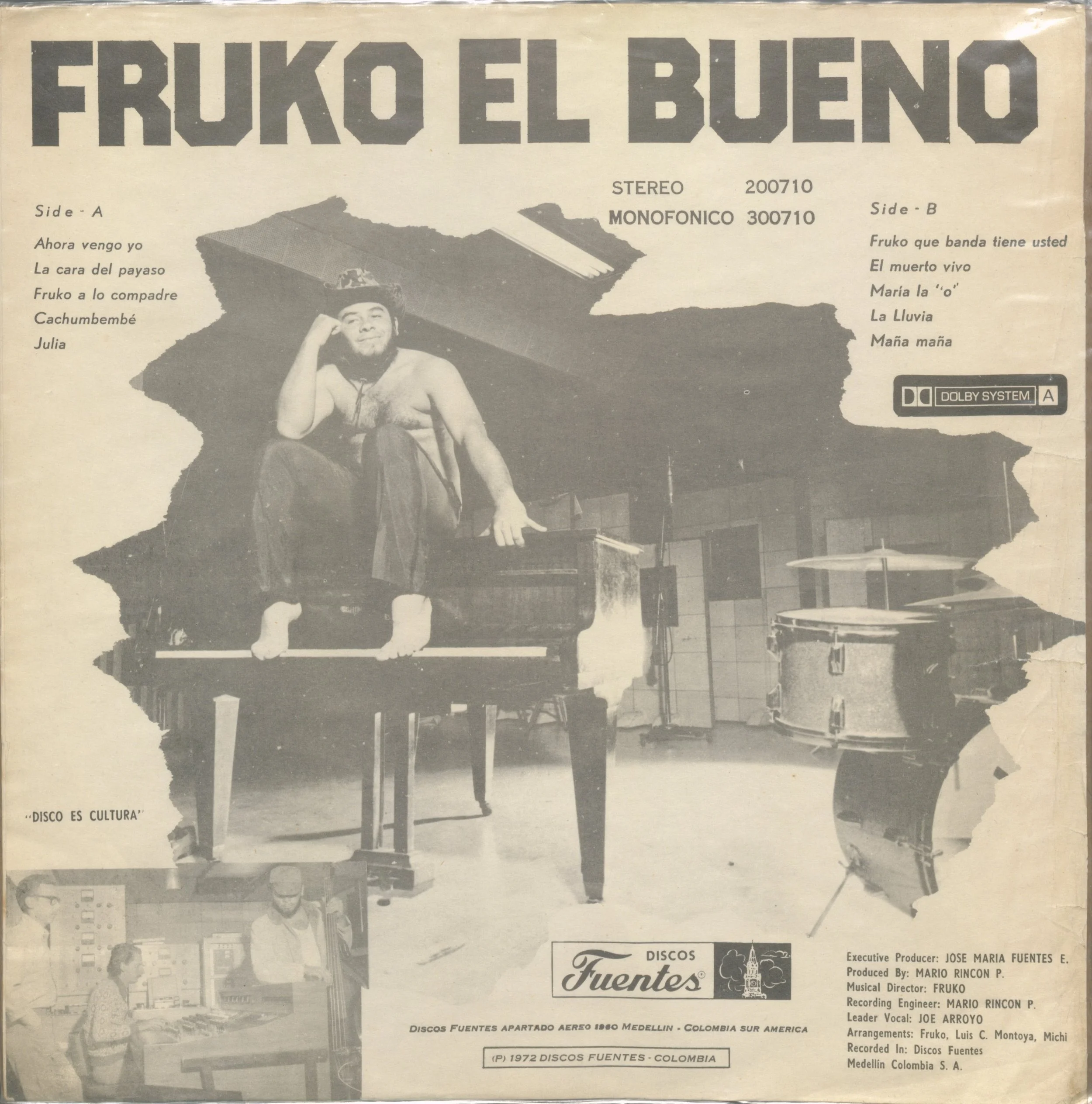

Manyoma, it seemed, also caught a lucky break. The group’s bandleader (and Rincón’s nephew), Julio Ernesto Estrada Rincón, better known by his nickname, “Fruko”—inspired in jest by his apparent likeness to a cartoon mascot associated with Colombia’s best-selling ketchup—initially planned for star vocalist Joe Arroyo to sing the tune. Arroyo was unavailable; Fruko and Rincón gave it to Manyoma instead. Manyoma died in February of 2025 with a series of obituaries recognizing “El Preso” as his signature song in a lengthy tenure with Colombia’s most celebrated salsa orchestra.

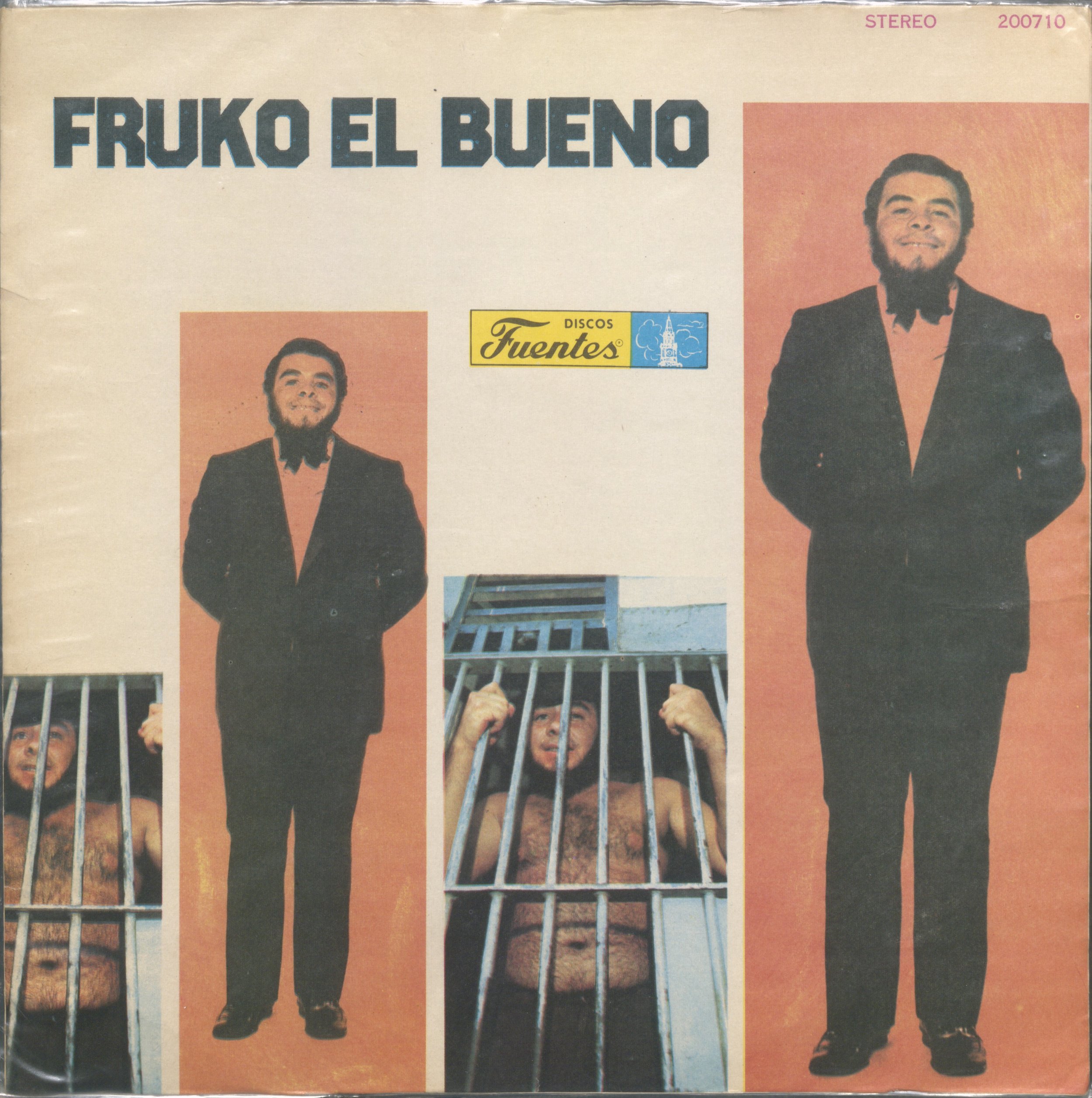

Fruko and his “Tesos”—Colombian slang for “tough guys,” inspired by Fania Records’s slew of “bad boy” salsa stars and their respective mafia-exploitation album covers—adopted New York–style salsa into a distinct Colombian hybrid. The group soon minted its own salsa records and faux-gangster album covers, a novel experiment for the tropical music–focused Discos Fuentes, with their hard-salsa LP debut, Tesura, in 1970. The next several years ushered in a series of popular singles and albums from the group as Discos Fuentes and other Colombian labels seized on the popularity of salsa. Medellín, Buenaventura, and Cali—an urban salsa haven in the Valle de Cauca, the Pacific department home to the Andean nation’s largest Black population—emerged as the interior strongholds for salsa andina and salsa dance culture.

Rincón came to Discos Fuentes in 1960 upon the label’s relocation to Medellín, founded decades prior by the enterprising Antonio “Toño” Fuentes in his native home in the Caribbean port city of Cartagena. Later, rising to become the label’s chief studio engineer, Rincón helped usher in a ‘60s-era golden age in Colombian music, especially in its tropical varieties—genres favored by the elder Fuentes—in porro, mapalé, gaita, cumbia, and other cross-pollinated sounds of the Atlantic coastal region. Rincón blazed a new trail for the industrious label by producing the nation’s first stereophonic recording—a proud milestone that inspired Fuentes to send his first hi-fidelity pressing to then-President Alberto Lleras Camargo. Years later, Fuentes dispatched his son and studio engineer, José María, along with Rincón, to scoop up a piece of used studio equipment—a graphic equalizer—from Johnny Pacheco and Jerry Masucci’s Fania Records salsa headquarters in New York City. Fania’s new studio honcho, Jon Fausty, agreed to train them on the outdated EQ and demonstrate studio techniques in the duo’s bid to catch a bit of the Fania magic to bring into the Fuentes operation.

José María, meanwhile, helped persuade his father to move the label into the bold new frontiers of salsa, later cofounding Fruko y sus Tesos and the Latin Brothers, another major Colombian salsa group (initially led by Fruko) on the label roster. “I stayed there and just kept learning, and learning, and learning,” Rincón recalls of his Fania apprenticeship. It wouldn’t be long before popular Discos Fuentes artists, including cumbia stars Los Corraleros de Majagual and Fruko y sus Tesos, started crossing over into the U.S. (with the help of their Florida-based Miami Records pressing/distribution affiliate) and touring New York and elsewhere, including the latter’s headlining of a major salsa concert at Madison Square Garden as the storied venue’s first Colombian ensemble. An entire Los Corraleros de Majagual album, Ésta Sí Es Salsa!, crafted in the grip of ‘70s salsa mania depicted the snazzy, mod-suited Colombian tropical band in front of the George Washington Bridge in Manhattan’s Latinx enclave of Washington Heights.

“El Preso” capped a years-long creative streak for the popular Colombian orchestra, which, alongside major hits from Venezuela’s Dimension Latina and others, reoriented salsa music toward its Global South origins. Back in North America, the early-to-mid 1970s saw the rise and peak of the Fania Records empire—the “Motown of Latin music”—with the label supergroup, the Fania All-Stars, packing iconic New York venues from Greenwich Village’s Red Garter Club to a milestone 40,000-plus crowd at Yankee Stadium. The All-Stars’s August 1971 performance at the Cheetah Club, formerly known as the Palm Gardens, a Midtown haven for the short-lived boogaloo craze, turned into Latin music’s generation-defining, Woodstock-film-level event as Leon Gast’s 1972 concert film, Our Latin Thing. Gast’s slice-of-barrio-life film is partly, if not mostly responsible, as acclaimed NYU Latino Studies scholar Juan Flores affirmed, for forging the “master narrative” of Fania Records’s synonymity with salsa.

Beyond its reputation as a Colombian salsa classic, “El Preso” draws from an older song-form tradition found deep in the annals of Latin music: the lament, or “a crying out in grief.” (True to form, Manyoma’s wailing gritos throughout the chorus—ay, ay, ay!—certainly sounds apropos for the poetic style.)

Within New York’s layered Latino histories, a century ago reveals a time and place when newly arriving Puerto Ricans—“citizens yet foreigners,” in the words of Latino historian and Democracy Now! cohost Juan González—were migrating en masse to “Spanish Harlem” and elsewhere to help spread Caribbean island music across the island of Manhattan. Out of this era, one of the earliest hit songs in Latin music history, “Lamento Borincano”—written by Afro-Puerto Rican musician and WWI veteran Rafael Hernández, recorded by Canario y su Grupo at RCA Victor’s Manhattan studios in 1930—expressed a type of “grief-cry” that invoked symbolic themes in longing for island home and jíbaro, or farm peasant, class struggle.

Hernández’s lament emerged in the context of anticolonial struggle and U.S. imperial domination of the island, articulating a type of Du Boisian “double consciousness” in Puerto Rican colonial identity increasingly situated within a mainland-island dichotomy.

“El Preso,” a Colombian lament that invoked a new type of struggle for Andean Latin Americans, reinforced this established motif found in working-class, Afro-Latin music from its earliest origins in the recording industry. 1975 marked a year when “El Preso” broke Colombian record sales (domestically and internationally, as both 7” single and popular El Grande LP and redefined Colombian music through a powerful anti-prison anthem as Colombians themselves became increasingly subject to reductive North American stereotypes and persecutions as “narcos” and cartel criminals. Like Hernández’s lament, “El Preso” originated in a decade succeeding a major policy pivot in Washington on immigration.

In 1965, the 82nd U.S. Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, a landmark immigration law in a sweeping era of liberal reform that ended decades of a racist quota system and sparked new waves of Latin American immigration, including a first-ever major tide of Colombians to the nation, adding new layers in New York’s expanding Latino demography into the outer-borough reaches of Brooklyn and Queens.

Fifty years later, “El Preso” feels ever relevant as Colombians and other Andean nationals are subject to renewed criticisms—including an ongoing gunboat diplomacy and open assassination campaign—from the highest echelons of U.S. state power as so-called “narcoterrorist” threats to the nation. And as the North American carceral state, with its Black- and brown- majority population, has only ballooned in the intervening decades.

As the Senate’s Church Committee revealed those five decades ago, a toxic cocktail of red-scare paranoia and regime-change fever undergirded a decades-long terror campaign to reshape Latin America (and elsewhere) into a postwar landscape of U.S.-friendly puppet states. The echoes of lament throughout Colombian salsa—invoking frequent themes in social and racial justice and more than several anti-carceral anthems—evolved from the socio-political milieu of “El Preso” to its sensational 1980s heyday and into an ongoing renaissance with the conscientious now-sounds of Bogotá’s Meridian Brothers and La Pambelé, amongst others. “Fellow prisoners, people of all classes,” Manyoma sang in an intensifying call-and-response at the song’s end, receiving his summary answer by the chorus response: “Alone in my sorrow, alone in my condemnation.”