An Ode to the World's Borough

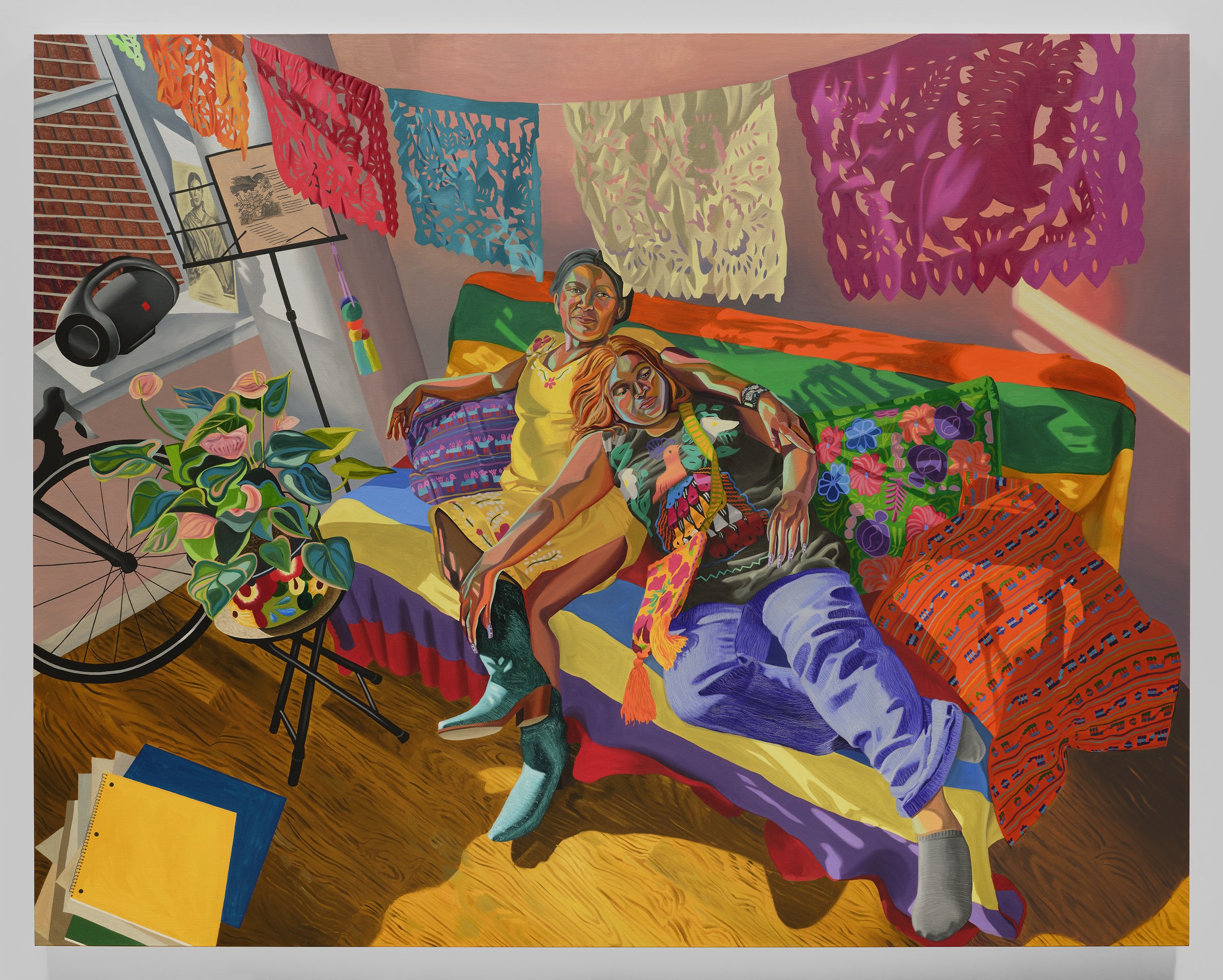

The Queens Museum presents Aliza Nisenbaum’s first New York museum solo exhibition, Queens, Lindo y Querido, on view from April 23 through September 10, 2023. The artworks by the Mexican-American artist recount years spent engaging with the Museum and the diverse community of transit workers, intergenerational immigrant families, and members of grassroots organizations who call Queens home, celebrating its people in contextually rich settings and exuberant colors. About a month away from the show’s opening, I had the opportunity of speaking with Nisenbaum about her intertwining experiences as an artist and educator as the basis for her socially conscious practice.

—

Sebastián Meltz-Collazo: When and how did your interest in the community of Corona, Queens begin, and how do you view this initial experience with this community as an evolution in your artistic practice?

Aliza Nisenbaum: It was in 2012 when I asked Tania Bruguera if I could participate in Immigrant Movement International (IMI), and she mentioned that what was most needed at the time was English Language Skills. I came up with a hybrid program in which I taught English through feminist art history to a group of women because they were asking about images from women artists. I got interested in their stories from getting to know them. After teaching that class, I asked Tania if I could paint in that space itself. So I remained friends with people who took that class, especially Veronica and Marissa, who since 10 years ago I’ve been painting on and off. My work is very much about witnessing particular groups of people that I’ve invited to paint or taught. And most recently, I’ve been embedded in Corona, working with the museum for about two years, during which I did a piece for LaGuardia Airport. It’s a mural that celebrates sixteen workers from the airport, so I got to be here, get to know them, and paint them.

SMC: That’s beautiful. And from looking at these pieces, you must feel like it’s the culmination of these relationships and your entire process for this show.

AN: Absolutely! In this painting (she points at Eloina, Angie, Emma, Abril y Marleny, Despensa de Alimentos, Queens Museum, 2023) you can see La Jornada food pantry, which is sponsored by the museum. It happens every Wednesday, right outside my studio, and they’ve been sponsoring this for the community throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. They have fed thousands of families during that time. And so they [the volunteers] were really interested in art and what happens in the rest of the Museum. So I offered to teach a class for the volunteers who distribute the food every Wednesday. So here (pointing at the painting El Taller, Queens Museum, 2023) you can see the students at work from this class, which I titled “Art and Identity”. It’s a class that ran these past two semesters and grew organically out of the one I taught in the past with Tania at IMI. They’re really partaking in a gift economy, where they give of their time with the pantry, and we were able to give a class to them to meet their interests. You can see some of them in various paintings from different instances throughout the two years I’ve been here; Día de los Muertos, the pantry on Wednesdays, and many evenings that we would sit upstairs looking out at the Unisphere and the park.

SMC: It’s fascinating because it makes me think of how you've made yourself available to give resources like translations and art history, as well as being here during these kinds of events. I feel that you saw the potential that arises when spaces like these are turned into something different from what they are primarily. And that kind of bridges a gap between people and institutions differently, where one could think, “Oh, we're here serving food, but this is a museum, so what's also going on here?”

AN: Totally! IMI provided services for the community in Corona, and in turn, people started to get very curious about the art world and the art market. For example, the first pieces I made I gave to Veronica. So in a way, they started to participate in the art world and later began to make art themselves. And their work will be hanging along with mine in the museum. We'll be recreating the Taller, with their easels and everything, and we'll have workshops led by them! Miguel Flores is going to give a class on portraiture, while Luz Caicedo and her husband Samir Urdinola will give one on color and landscape, surrounded by their own works.

SMC: I'd be so excited to see how the class participants react to this painting, realizing that they're in it as well as their own artworks. As we're talking about it, El Taller makes me think of how history painters in the 17 and 1800s would insert references to other paintings in their own pieces. I see you embracing this notion of legitimizing artworks into a canon of history with these people’s works and experiences.

AN: I'm really interested in history painting because my paintings accrue over a really long period of time. So it's this idea of starting somewhere to then keep adding more and more information. I was looking at the Alex Katz show, at the Guggenheim, and how he painted all these people from the back, leading into the painting. I was also thinking about Olga Costa’s painting The Fruit Vendor, which was on the cover of the books of the SEP (Secretary of Public Education) in Mexico when I was a kid. It's a classic that displays all kinds of fruits from a place, so I’m thinking how La Jornada is also a cultural food pantry with all the tortillas, cilantro, avocados, corn, peppers, all kinds of flowers, etc.

SMC: Do you see your current practice as being a voice for a community, considering how you make art within a participatory context?

AN: I don't think of it as a voice, rather it's more adjacent to, like witnessing. I think about my work sometimes as a platform for different configurations to come together. When I make a painting of a group, it brings about a new community in some ways. These people who participated with me are now going to lead art classes and expand. Because they've formed a new community through the work. So sometimes these configurations, grouping people, assemble them in different ways.

SMC: It becomes a vehicle for gathering people that otherwise wouldn't be in the same room, so to speak. But they are in this painting!

AN: And that allows for all kinds of conversations to happen. These people from 10 years ago will be talking with the people I’ve met over the last two years. Here we have Andra (pointing at Andra, 2022), who's been a Facilities Manager at the Queens Museum for more than 30 years. I would walk by his office and he was the first person to greet me every time I came to the museum. So one day I asked if I [could] see his office. And they were celebrating his 30th anniversary at the museum, so I thought I’d paint him with what he has in the office. And he's also participated in food pantries, so he’s in relation to this food pantry that's happening here. So it’s like domino pieces that are in conversation, new configurations.

SMC: There are different worlds that you're involved with, but you're creating the connections through your own paintings, to have them meet each other in a sense.

AN: There's something about aesthetics, the making something beautiful and colorful, that becomes a starting point. It's like a celebration or a party, like a dance club. I used to paint dancers, and a dance club can be a special place that brings all kinds of people together, creating new configurations that can be very political in that space. There is that potential. And I think that painting and the use of color can be a celebratory moment, with the potential to bring people together, even when you never know what the repercussions to be of that. But then other conversations can take place.

SMC: And it’s a great invitation for others to witness what you have witnessed.

AN: Yes, like the slow process of witnessing I go through as I paint, spending time with people as the work brings them together. We're also going to have a panel discussion with some people from these paintings and Veronica Ramírez, who runs Mujeres en Movimiento. She also lives in Corona, so some of them do know each other already, but we'll have a panel discussion with them talking about the work they do.

SMC: I love how you're describing the slow process of the painting and how that takes on different layers of meaning. Do you see your painting process, which you acknowledge as slow and deliberate, as a resultant function that mirrors the time you’ve spent reaching goals or breakthroughs when volunteering and giving workshops?

AN: Absolutely. I think that teaching is very much about creating space for people to experiment and surprise the teacher, and for that to be mutual. And painting is so much like that also, in the sense that you don't know where it's going to go. This weekend I'll put some finishing touches to these, and I’ll finally get to see it. But it's an activity in which you don't know when it's done until it surprises you in some ways. And I think that's very much like teaching too.

SMC: You have an understanding of the patience and effort it takes to get to know people, both when you teach and when you paint.

AN: It was really satisfying, after having left my Columbia job, to teach this group. Miguel, who’s in the class, one day talked about how there’s always been a strong tradition of art in South and Central American countries, but some people are working so hard that they hadn't given themselves the opportunity to have an aesthetic expression. And this is the first time I've taught in Spanish in a really long time, especially an art class! And so much of my emotional vocabulary from when I was growing up is in Spanish. It was refreshing to share certain words or phrases with them. For instance, I was explaining to someone recently the expression “un ojo al gato y otro al garabato”; sometimes when you paint you have to have your eyes crossed, so to speak. You have to see a bit out of focus, be a little reckless, and that will allow you to make bold moves. And it was through speaking Spanish that I remembered parts of myself, parts of my identity that might have been lost through the 24 years that I've been in the US. It just goes to show how complex identity can be, where some parts are lodged in one language and some parts in another, while both live inside you. So it was very satisfying to talk to them about art and to create the space for them to grow as artists.

Sebastián Meltz-Collazo is a writer, visual artist, and musician working towards new experiences through the intersection of narratives. Connecting personal with collective histories, he explores iterations of visual culture and representation with the intention of raising questions around identity and its various manifestations. He is a graduate of Image Text Ithaca and is based in New York & Puerto Rico.