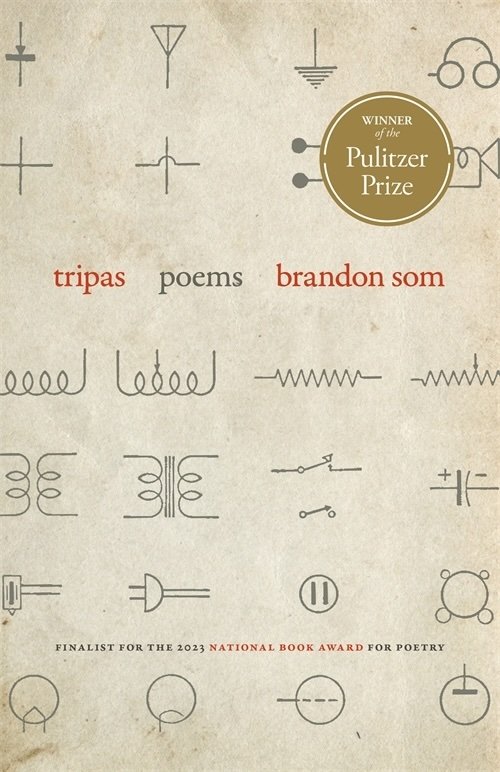

Poetic Engenderings of Asian Latinx Memories

Reading Brandon Som’s poetry collection, Tripas (2023), the text’s questioning reveals a latent secret: “A hiss that can’t hush its violence how might it sound a resistance too.” Locally emplaced in the Southwest, against the background of mesquite trees in Arizona, Tripas’s storytelling quickly expands in historical and geographical scale, as Som critically reconstructs wayward routes of multigenerational Chinese and Mexican family migrations entangled with 20th-century immigration restrictions and the transnational circuits of globalized capital. Poignant character studies of Som’s maternal grandparents Nana, his Chicana grandmother who worked the assembly line at Motorola in Phoenix, and Tata; paternal Chinese grandparents Ng Ng and Yeh Yeh, who emigrated in the 1920s from Guangzhou, evading Chinese Exclusion as a “paper son”; and Chinese American father, who owned a corner store outside of Avondale; serve as the backbone of this intimate book.

Tripas weaves an intergenerational “Xicanese” narrative that transcribes familial memory while interrogating Chinese Chicano identity formation, cultural memory, and Asian Latinx community survival practices.

A meticulously researched and engaging text proliferating with historical, artistic, and etymological references, Tripas moves deftly between languages (English, Spanish, Chinese) and genres of memoir, poetry, and literary narrative with rare dexterity. Som’s book also sits in a unique position within contemporary, minority literatures, as its exploration of multicultural identity, labor, immigration, and social history cuts across Asian American, Latinx, and Chicanx formations. By way of interwoven, passed down recollections that come alive through aesthetic registers of image and sound, Som’s poems bring his multicultural identities, Asian American and Latinx immigrant communities, and histories closer together in intimate relation, attuning us to the prophetic beauty of everyday Asian American and Latinx life-making.

Amid verse both fluid and searching, Som conveys the construction of multicultural identity as a multilingual, learned process, between self-teaching Chinese characters with a dictionary in hand, lessons in Spanish class, personal investigations into Nahuatl roots, and informal homeschooling from Nana and aunt Ai Gu. Tripas’s orality, which emerges from Som’s inventive wordplay along with a constant code-switching between Spanish, English, and Chinese, challenges silences within Latinidad regarding Asian heritages, histories, and cultures, while marking the long-standing, heard presence of multicultural identities, communities, and encounters in the borderlands. Turning to “Code Switches”:

Cómo se dice, my circuitry, sews me––me cose––

word by word & dictates––how do you say?

[…]

There’s lightning in the Chinese 電,

but I see lasso & chain link in the componentry,

an analemma tracing dagongmei & ensambladoras

from rural town to city factory.

While poems like “Chino” and “Half” tarry with the complexity of mixed racialized subjectivity, including feelings of shame stemming from racial difference and gaps in understanding Spanish and Chinese, Tripas’s cómo se dice poetics moves beyond poles of negativity informed by colonial racial formations and exclusionary racial ideologies such as mestizaje. Som forges Chinese Chicano identity through a new perspective (“What does that dark eye in the ear’s husk see?”), a relational optic that sees across––and attempts to reconnect, as the em dashes in “Code Switches” enact––the “circuitry” of fragmented lineages and multiple cultures, languages, and histories.

For the most part, Som refuses to directly explain his family tree or chart the relations between his communities within individual poems, opting instead to allow readers to make their own connections throughout the poetry collection. This creates a readerly experience both open to mishearing or misinterpretation and revelation through poetic form that mirrors the limitations and possibilities of recuperating fragmented familial narratives of labor and migration.

Sounding and imaging Spanish, English, and Chinese words together in “Code Switches,” Som underlines the revelatory work of sayings that unfold to make critical connections with global gendered economies of labor exploitation. Tripas details the emergence of the speaker’s political consciousness through firsthand awareness of social and environmental injustices, ranging from Motorola exposing workers to and polluting Phoenix’s environment with toxic solvents including the carcinogenic trichloroethylene (TCE) to gender-based violence and the murders of female maquila workers in Juárez, Mexico. Dwelling on the image of the Chinese character for “electricity” and “lightning,” the poem’s speaker visualizes an entanglement between Asian and Latinx feminized labor, creating a transpacific and feminist political imaginary between the women whose work drives global supply chain capitalism from China to the U.S.–Mexico borderlands.

Through poetic language, Tripas explores the transmission of cultural memory and knowledge through food and foodmaking as an Asian Latinx gendered practice of intergenerational care. In intimate recollections of Nana and Ng Ng, Som observes something holy in the quiet patience of their cooking rituals.

Considering “Tattoo,” wherein Som notices with reverence Nana’s kneading, “corn silk on husking hands,” while listening to her tell a family story:

Her abuelos in the barrio Cuatro Milpas,

like the ranchera, tended field corn,

she tells me, for their tienda [. . .]

Sold masa, she says, from horse-cart,

harvested stalks after their first silk,

peeled from ears the leaves to lay out––

their green yellowing in the day’s heat

––& then simmered the shelled grain

in a wood ash lye for the nixtamal––

a Nahuatl word with ash in the root

as if the word were recipe or how-to.

Through Nana’s voice, which transmits intergenerational and Indigenous knowledges of making masa, Som recovers a Latinidad connected to land-based practices for sustenance and survival. Sounding out the violent “hiss” that emanates from the coupling of “masa” with “mace’s trace” and utilizing poetic techniques of enjambment, Som follows the metaphorical grooves in the barrio’s “furrows,” “its bellows crop lines, song-citing/ larger histories of upheaval & loss.” The poem melodizes the cultural memory of land-based relation with the sorrowful tune of histories of Spanish colonization in the Americas, socioeconomic inequities, and racial divisions, including “redlining & covenants/ that kept neighborhoods Anglo only,” referring to the establishment of areas such as Cuatro Milpas and El Campito, predominantly Mexican, working-class barrios in 1900s Phoenix.

In “My Father’s Perm,” Som brings us to Ng Ng’s kitchen through an intimate gaze:

beside the sink

where she washed her rice,

hands pressed

as if to pray

but with grains

whispering instead

between them.

Tripas approaches foodmaking as a source of Asian diasporic memory, as Som recalls Ng Ng’s vegetable garden, where:

she labored—scarecrowed

with bow rake

& whipping the hose free.

Sowing here what

she knew over there,

with jute bag

of cabbage & lotus root,

she reaped against

the loss.

Through Nana and Ng Ng’s cooking, Som limns the centrality of foodmaking for immigrants in maintaining transnational cultural attachments while creating a new life, engaging the repeated imagery of furrows to metaphorically express the labor of belonging in the aftermath of differing migratory losses.

Tripas theorizes Nana and Ng Ng’s cooking and acts of care as practices of reproductive labor, a labor often invisibilized and performed by women in the family. Som’s attention to what exceeds the circuits of global capitalism, what scholar and critical theorist Neferti X. M. Tadiar theorizes as “remaindered” forms of making and sustaining life, is astonishing in its imagining of both small, subversive acts on the assembly line, and following the temporal rhythms of love and care that fill in the hours between the punch of the time card.

Tripas crafts a poetic vision of community survival, weaving a vibrant tapestry between Som’s family’s labor and a wider, social world of intercultural interaction between Asian American and Latinx immigrant communities. One of the text’s central settings is that of the family’s corner shop, a well-known site of the Chinese American experience, and, importantly, a place where interethnic social bonds have historically been forged in the borderlands. Som’s poetic eye sees and ear hears moments of radiating beauty in his grandparents and father’s everyday work of shopkeeping, memorializing the echoes of their labor (an unidentified woman, most likely Ng Ng’s, voice and “-ah”s that dance through the shop’s physical space in “Inventory,” “& the shrill sound as he sharpened his knives./ My father’s cuts were calligraphy too,” in the final section of mournful poems, “Novena”). Earlier on, in “Raspadas,” Som also recounts his maternal great-grandmother Nana Chayo’s (“In raspar,/ hear her voice’s/ saw scratch”) home storefront in nearby Barrio Campito, where she sold the shaved iced treats across the street from where Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chávez held a hunger strike in 1972.

These details and anecdotes, the work of memory, ties the stories of Som’s family with Asian and Latinx histories of oppression, survival, and resistance, ranging from Latinx labor movements to a transnational network of Asian diasporic shopkeeping created during the Chinese Exclusion era. Crucially, Tripas confronts the erasure of histories of racialization from dominant national narratives, not only illustrating, as scholar Susan Thananopavarn notes in LatinAsian Cartographies: History, Writing, and the National Imaginary, “similarities [of legal and social exclusion] in Asian American and Latina/o experiences of U.S. . . .nativistic racism,” but charting lesser-known, hemispheric entanglements with 20th-century histories of racial violence and expulsion against Chinese Mexicans.

While visiting Mexico City’s barrio chino, and in the eponymous grocery “Super Mercado Lee Hou,” the speaker contemplates:

On market signs

in Sharpie & Spanish

naming the ‘Products of China,’

we might read stevedores

on galleons, coolies of empire,

[…]

Their descendants sold

sundries in the 1930s

in the copper towns of Sonora

before they were run out

by ordinance, by anti-chino

violence.

Tying the movement of market goods with peoples, Som connects a centuries-long arc of transpacific labor migrations between Asia and the Americas to histories of trade, commerce, and empire. Further considering the crossing of 20th-century Mexican antichinismo, state-sponsored racial discrimination and violence against Mexican Chinese populations, with President Herbert Hoover’s deportations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans during the Great Depression, the speaker asks: “Could I sign my name/ that crossing, that chiasmus/ of exile, or simply share/ a night’s receipts.”

If, as Rigoberto González notes in his praise for Tripas, Som amplifies “not collision but coalition” between his ancestries and communities, the tone of ambivalence that marks the indirect question folded across these lines, missing the question mark of an interrogative, also acknowledges that solidarities between Asian and Latinx communities are at times uneasy, or difficult to see or perceive.

As scholar Long Le-Khac argues in Giving Form to an Asian and Latinx America, literary works and their aesthetic practices can make the emergent political formation of an Asian and Latinx America palpable “across a divided racial order, stratified immigration system, and unequal world labor market” and “envision distinct stories of struggle as part of a broader world of injustices.” Tripas doesn’t elucidate an explicit politics. Instead, engaging the possibilities of poetic form, Som relies on aesthetic maneuvers such as the collapsing of time and space and visual arrangement to chart continuities and expose intersections between Asian and Latinx histories of relational racial formation. Read together with other poems such as “Resistors” and “Qingming,” Tripas stays with the potential of recognizing interlocking systems that have historically perpetuated the disposability of racialized life (settler colonialism, imperialism, the nation-state, capitalism) for building political coalitions among minority groups across national borders and racial lines.

This recognition, as Som points out, can also come from listening to the echoes of the dead and mobilizing their memory into political action. Through the sounded emphasis of alliteration, “Qingming” builds an emotional sense of collective grief: “I go to my dad’s gravestone/ in its granite row of grocer’s graves/ saying Harlins, saying Garner, saying Floyd” and “Better to listen/ inside those unnameable spaces that call in/ our dead, who ask that we do more than grieve.”

Far from universalizing or essentializing Asian Latinx identity, Tripas operates in the key of multiplicity and difference, attending to the intimate contours of one family’s experience, underlining specificities of class, gender, race, and ethnicity. Tripas’s importance lies in what it produces through language: new subjectivities and identities engendered from Asian and Latinx historical and cultural crossings sparsely interrogated in literary and cultural production.

Eschewing an appeal to representational inclusion, Tripas activates the intersection of Asian Latinx from an oppositional standpoint, critiquing contemporary social injustices including labor exploitation, gentrification, and racial discrimination and violence within a global matrix of colonial and racial power, while drawing on cultural memories of Asian American and Latinx relation and shared histories, as a political grounds for coalitional possibility. This is a timely, teachable poetry collection, urgent and necessary in responding to this moment of renewed social violence against migrants and racialized others with the vitality of community and the political spark of organized resistance.