The Embodied Mask: Elia Alba’s Photography and Soft Sculpture

Working as an artist since the late 1990s, Elia Alba has created an entire body of sculptural work and performance-based photography that focuses on difference.¹ Among her most important works is a series of “bodysuits” now in the collection of El Museo del Barrio. If I Were A… (2003) presents the body of the artist in the guise of three different racialized bodies that are coded according to skin color. Alba created the bodies that adorn the bodysuits through a digital collage process. The artist first photographed her nude body, digitized the images, and then manipulated her skin tone to create a kind of “quilted” figure. Through this method, she created three bodies, a “white” body, a “Black” body, and a “mixed” or miscegenated version of the two. This exploration of racialized and gendered bodies is a throughline in the artist’s body of work.

In 1998, Alba entered the prestigious and highly competitive Studio Museum in Harlem’s artist-in-residence program. She and the Newark-born Puerto Rican artist Manuel Acevedo were the first Latinx artists to receive an invitation to participate. That year, she began to create her signature soft sculptures from fabric. This work in photography and fabric, and the labor of women associated with fabric, has remained a crucial part of her work, which specifically addresses the complexities of miscegenation and the interpretation of the body as a product of multiple and competing characteristics. Alba’s works consider the question that Franz Fanon noted about existence and the phenotype of the outward appearance: How does a body become racialized?

Fanon notes:

“Ontology—once it is finally admitted as leaving existence by the wayside—does not permit us to understand the being of the black man. For not only must the black man be black; he must be black in relation to the white man. Some critics will take it on themselves to remind us that this proposition has a converse. I say that this is false. The black man has no ontological resistance in the eyes of the white man. Overnight the Negro has been given two frames of reference within which he has had to place himself…His customs and the sources on which they were based, were wiped out because they were in conflict with a civilization that he did not know and that imposed itself on him.”²

The presence of white, Black, and “mixed” bodies literalize this relational fact of race as Fanon has described it. The racially collaged suit is the most revealing and underscores the role of the previous two. Manipulating the color and image of her own skin, the artist presents herself, in the third suit, in the guise of a patchwork rendering of racialized bodies and their subsequent mixtures. Like a post-modern, chilling version of a casta painting, she explores what her body might look like as a being that is a literal product of miscegenation.³ Across the Americas and the Caribbean, the process of racial mixing has been a source of historical pain and created a legacy of social, political, and economic constraint for those closest to Blackness. The artist symbolizes this history through the vessel of her body in three guises.

These figures—self-portraits—stand in relation to a real, human body, the photographic medium underscoring the realness, the physical accuracy of the image.

As body portraits, these partialed images represent radical departures from the way we understand real anatomy, but the photograph is there to assuage our fears, presenting a still-recognizable female body, alluding to a figure, a presence. The title of the work, If I Were A… leaves the completion of the phrase to the viewer’s imagination. We are left to consider what might happen if we fell into one of these three imperfect, fractured, and random categories based on skin tone. How would these variously colored bodies behave? How would they be interpreted in the social sphere?

In the video that accompanies these bodysuits, they enact various movements and personal gestures while being linked directly to the manual labor of women. Here, performance artist Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo tries on all three suits and considers his appearance. This image features clips of the artist’s mother sewing the bodysuits with her machine. The difference between Estévez’s body and the suit that covers it intends, perhaps, to be jarring but, more importantly, to signal difference and underscore desire. Upending tropes of gender, the bodysuit clearly fits a man’s body in a scale that would scarcely fit a woman’s. This purposeful, sometimes violent disconnect is a constant across the artist’s work. The performer in the video touches, observes, moves through a subtle narrative of desire that is both sexual and racial.

The inspiration for another series drawing on masks came from David Wojnarovic’s series, Rimbaud in New York, featuring the artist’s friends wearing masks with the face of Rimbaud across iconic New York City locations, in both public and semi-private moments. Rimbaud, a symbol of the ultimate outsider, renegade, protagonist of scandals, and a visionary poet, presides over these images of a New York City in 1978 and 1979, a post-Stonewall city in which art, love, sex, and drugs were plentiful, and the underground art and music scenes were flourishing. The incongruity between the body of the masked figure and the scale of Rimbaud’s face adds to the simultaneously whimsical and odd nature of the images.

For Wojnarovic saw Rimbaud’s life as a parallel to his own and envisioned these works as a way to make the queer body not just visible but also an occupier of multiple public spaces.

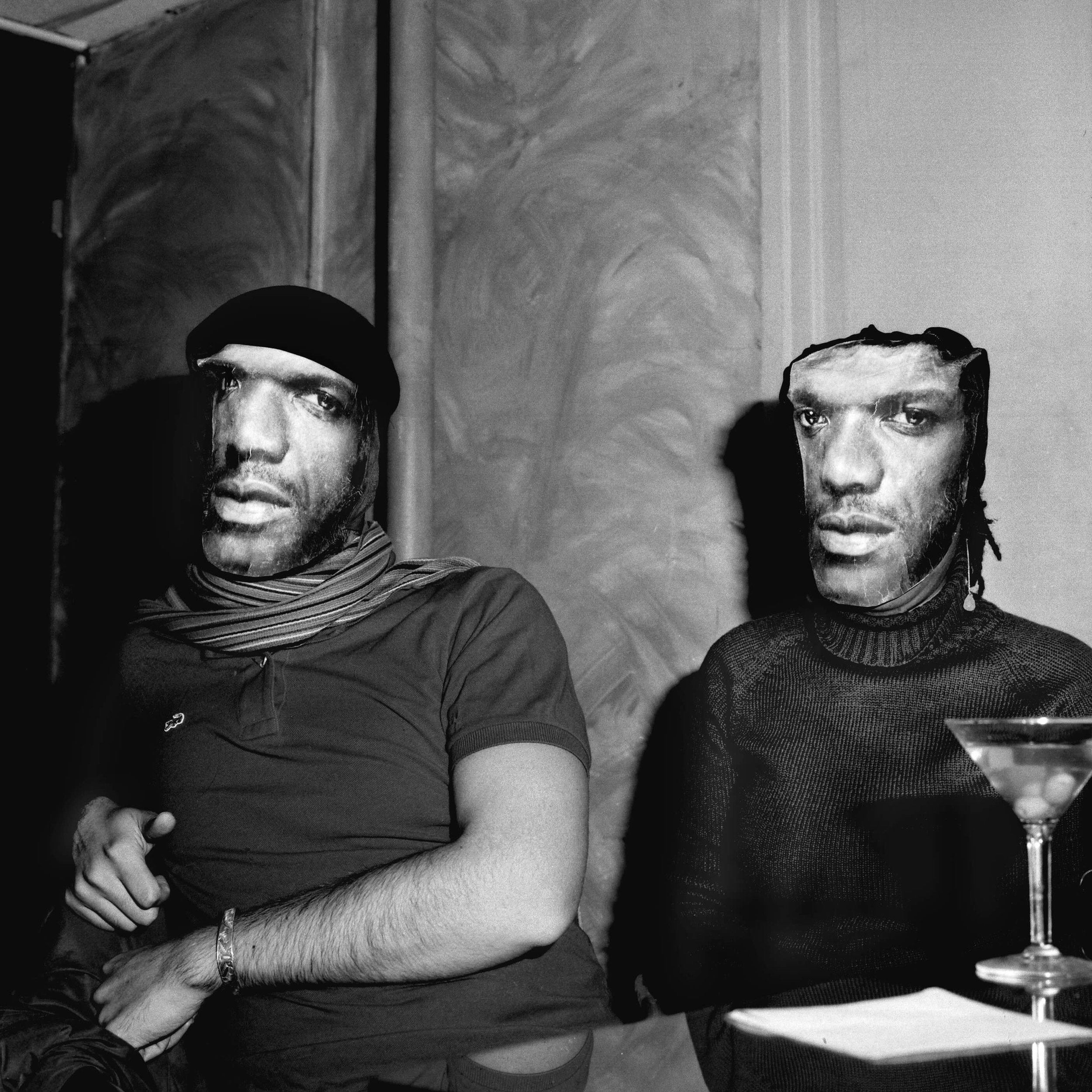

Alba’s works replicate the use of masking as a way to exist without revealing the true self but also as a way to heighten the visibility of bodies marked by difference. Placing her subjects in various scenarios, she records locations that are vaguely reminiscent of those in Wojnarowicz’s imagery but these take place in the South Bronx. The mask in this series is the face of Larry Levan, a well-known DJ who spun records and moved crowds at New York’s legendary Paradise Garage disco. Like Wojnarovic and Rimbaud, Levan was an outsider seeking acceptance in New York’s queer downtown club scene of the 1980s. His face, as a parallel to Rimbaud in Wojnarovic’s photos, presents a visual discourse that addresses race as well as sexuality. The masking gesture in this series builds on Alba’s earlier imagery that combines performance and masks of friends and relatives. Levan’s face layers additional meaning, specifying the location, the decade, the experience as one deeply tied to the gay, Black, and musical history of New York City.

The entire series of Levan photos were taken over two nights in the South Bronx in 2006. In one image, we have surprised a couple in a public bathroom. The figures both wear Levan’s face, again refuting expected gender iconography. The erotic pose, the form of the central female figure and Levan’s straightforward gaze recall the sensibility of Wojnarowicz’s images. Here are sex, form, body, urgency, secrecy, intimacy all bound up into a singular scene that hedges the difference between public and private, male and female, brown and Black.

In Larry Levan (Two Larrys) (2006), we see a parallel to Wojnarovic’s placement of a figure seated in the booth of a typical New York City diner. In Alba’s images, the difference in the scale of the face in the mask and the bodies adds to the element of fantasy and play, which is prominent in the images of bodies moving to (imagined) music, swaying together. All the bodies celebrate Black joy and movement is celebrated as they wear Levan’s face, becoming one with the DJ as he, in turn, moves them with his beats. This beautiful give and take between DJ and dancers act as a counternarrative to the more somber tones of Wojnarovic’s photos.

Alba’s use of photography, fabric, and performers in her imagery traces a line across her entire body of work. Throughout, the artist explores the relationship between the fact of gender and the social gendering of the body. She mixes the genders of masks and performers, gestures and coverings, body and face. Placing unexpected skin tones and genders together, she applies both masquerade and performance to a single still image to reflect on the social construction of identity through the deeply flawed surface reading of race and gender.

¹ Here, I use the word “difference” in multiple senses. First, as a constitutive part of one’s own identity, in which we understand ourselves as distinct from others, though still related in many ways. It also relates to the quote about racialization by Fanon used just after.

² Franz Fanon, “The Fact of Blackness,” Black Skin, White Masks, (New York: Grove Press, 2008): 29.

³ Castas were a genre of painting commissioned by the Spanish crown to understand the visualization of the mixing of races in the so-called New World. They were generally a set of 16 paintings, showing couples of different races and their offspring captured in moments of daily life.