Joiri Minaya: (Un)seeing the Tropics

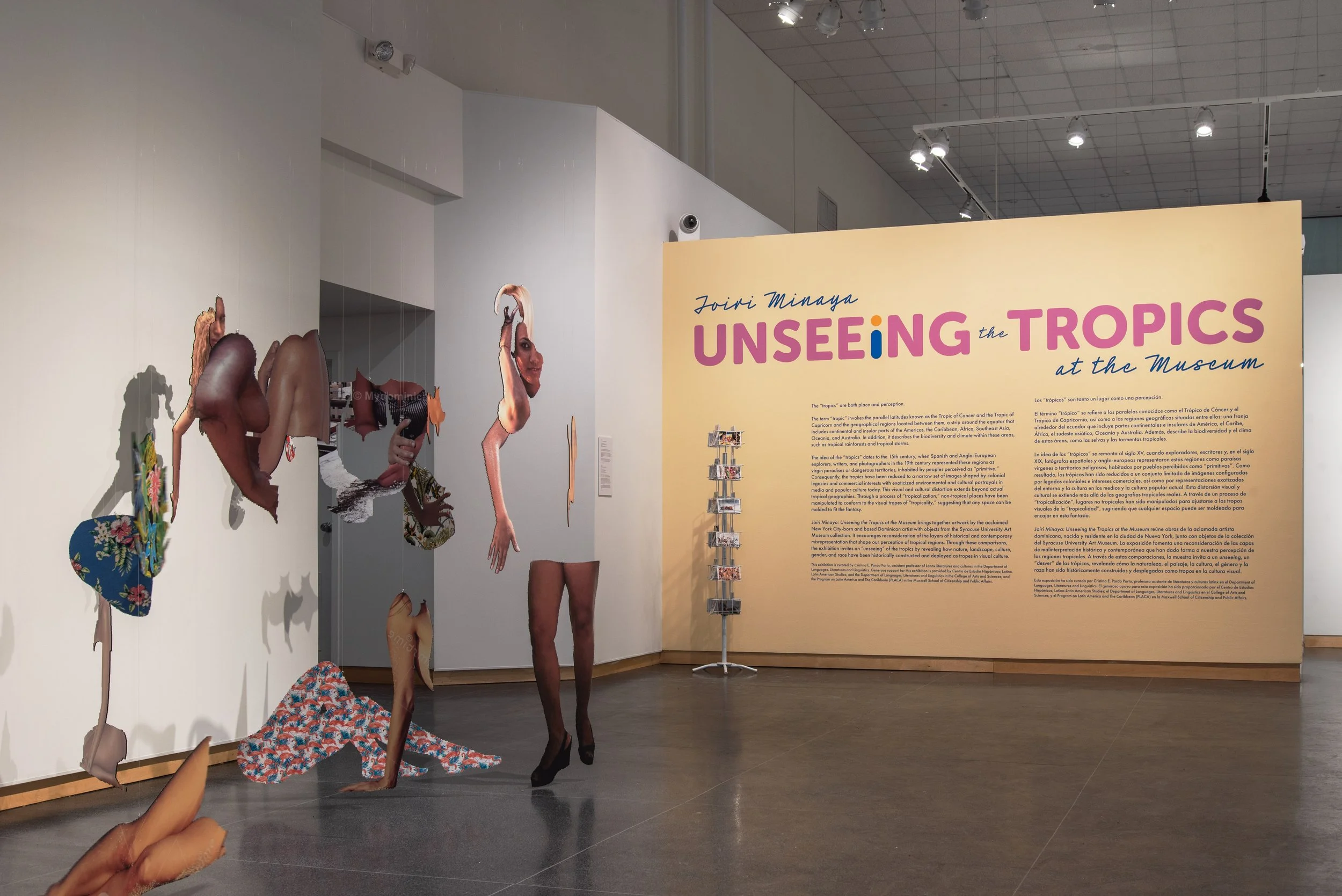

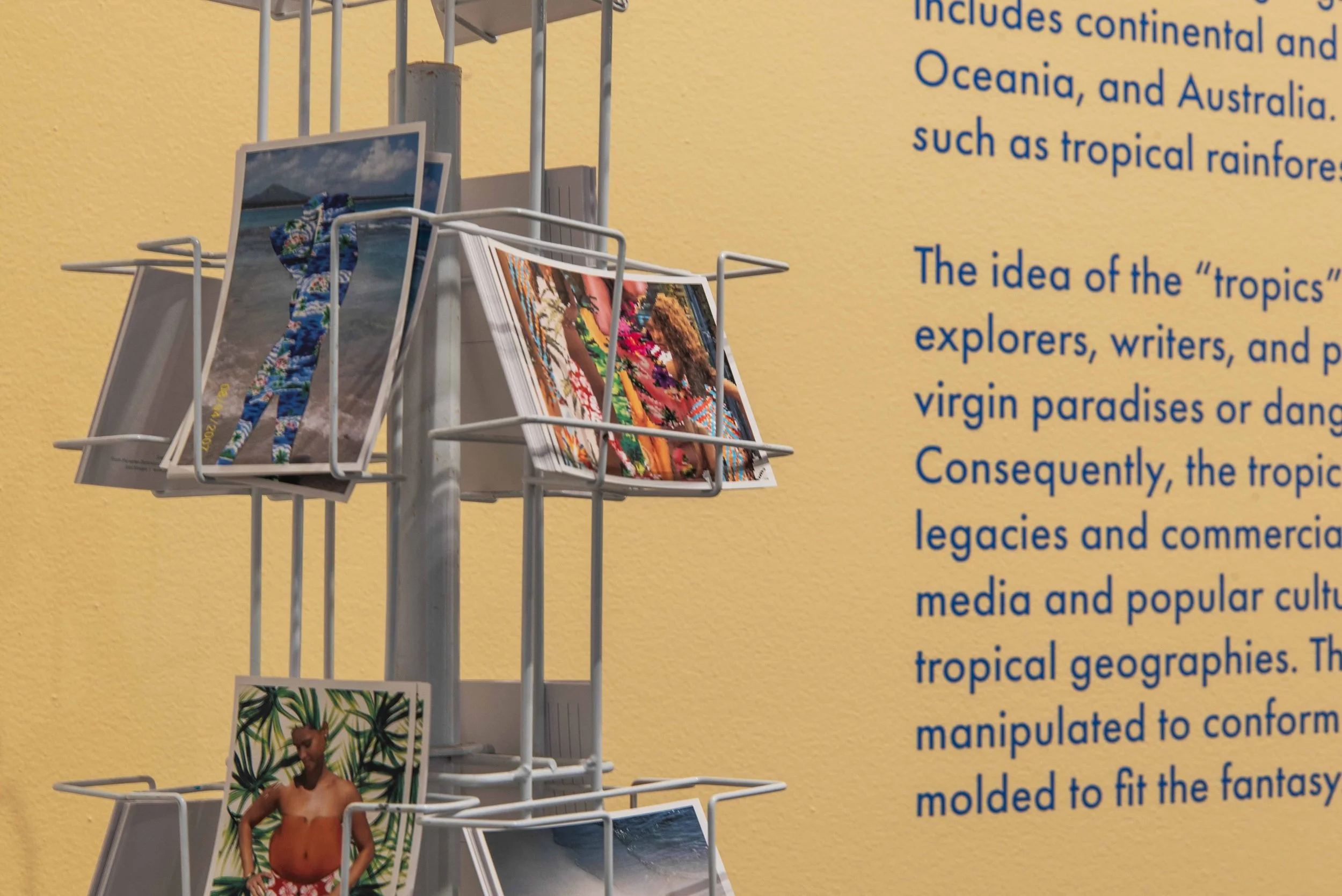

When you walk into Joiri Minaya’s exhibition at the Syracuse University Art Museum, one of the first things you see is a white steel-wire postcard rack—the kind you’d expect to find in any packed, slightly cluttered souvenir shop. It beckons you to pick one out, as if you’ve already landed on a tropical getaway and just need something glossy and rectangular to remember your vacation. But look closer, and Minaya’s sly wit begins to chip away at that tropical fantasy by twisting its familiar visual tropes.

I picked two cards. One shows a pixelated female silhouette in a flowery bikini, stiffly posed on white sand and overlaid with birds of paradise and fern leaves—like a glitch in a travel ad. Another features a collaged figure arching in awkward seduction: her body, assembled from Black and Brown parts, dissolving into waves like a mermaid losing her shape. Sea, beauty, bloom—all the usual promises. But Minaya draws on these visual clichés only to let them blur, stutter, and fall apart. The postcards enact what the exhibition’s title, Joiri Minaya: Unseeing the Tropics at the Museum, proposes: not a call to look away, but an invitation to undo the ease with which the act of looking turns both bodies and landscapes into objects of desire and consumption.

Minaya, who grew up in the Dominican Republic—now one of the most visited destinations in the Caribbean—knows intimately how the exoticizing gaze operates not only through tourism, but across the global visual economy, from fashion to advertising. Everyday textures influenced her artistic sensitivity. As a child, she spent hours in her mother’s clothing store, surrounded by tropical-patterned fabrics. Long before she could name the gaze, she was already deeply aware of its aesthetic codes.¹

But “the tropical” as we know it today does not emerge in a vacuum. As Krista A. Thompson writes, the postcard was never just a keepsake of personal memory. It once played a key role in promoting the Caribbean islands as both picturesque tourist paradises and properly governed colonial societies, smoothing over their natural and sociocultural specificities.² Contemporary tropical motifs still belong to that same visual repertoire of colonialist tropicalization. Minaya engages with this genealogy to explore the entanglements between power and seeing, expanding her archive across a variety of media, from ethnographic photographs and travel brochures to botanical illustrations.

Minaya particularly focuses on how historical sources persist and mutate within contemporary culture. In Continuum (2020), she stages a haunting juxtaposition by layering a stock image of “Dominican women,”pulled from a Google search, over a French anthropological photograph of a Somali woman posed on an animal-skin rug. Though time, geography, and medium separated the two images, they, as the title suggests, dovetail in composition and effect. Each depicts a female subject amid nature as sexually legible, seemingly arranged to gratify a lingering gaze. The work exposes how the fetishized representation of non-Western bodies has long circulated through the visual regimes of empire under shifting names: ethnography, tourism, digital indexing.

The image’s hand-braided palm-fiber frame catches the eye, showing Minaya’s subtle use of material language. Its rustic weave evokes craft markets and the curated “authenticity” of the handmade. More than a physical support, the frame extends the image’s meaning, performing fantasies of the native and the primitive. It also brings into focus the layered labor behind such objects: artisanal, artistic, and racialized low-wage work that continues to sustain Caribbean economies. Even without directly invoking plantation history, the piece surfaces its afterlives, echoing the gestures of hand-harvesting, picking, and cutting—forms of extraction and exploitation repackaged for aesthetic demand and consumption.

Also on view, Continuum II (2021) pairs an 18th-century Canadian painting of an enslaved Haitian woman with a contemporary travel brochure image of a juice vendor in Bávaro, a resort town in the Dominican Republic. Ruffled hems, vibrant tropical fruits, frontal poses, and welcoming smiles—coded onto the bodies of women of color—recur across both images, working to naturalize servitude as hospitality. The discordant collage confronts and disrupts the masculinist gaze, which conceals itself even as it aestheticizes and consumes the laboring, racialized female body.

Performance is a vital component of Minaya’s practice, positioning the female body as a site of autonomy and resistance. On the far wall of the gallery, two photographs document different moments from the artist’s long-term photo-video-performance project, Containers (2015–2020). In this series, Minaya and a group of female collaborators appear in various natural settings, fully enclosed in tropical-patterned spandex bodysuits that cover them from head to toe, revealing only their eyes. They play with the idea of opacity, evading easy apprehension.

In Container #7, a model poses at the threshold of a greenhouse, camouflaged in a bodysuit printed with a mix of monstera, fern, and palm designs. In Container #3, the scenery shifts to a tropical seascape. We see the protagonist’s back partially turned, arms raised, and hands crossed behind her head—a posture repeated a few times in the show. Both images appear against vivid wallpapers of fern or plumeria monomotifs. This layered mode of display underscores how the same visual stereotypes continue to bind the female body to domesticated nature and marketable aesthetics. The vibrancy and high saturation of the images only amplify their double edge. In them, visual appeal and violence intersect: For the viewer, the sensuous pleasure of looking is inseparable from the colonial histories of control and dominion that these images inevitably reanimate.

If Containers plays with visual deflection, Siboney (2014), a performance-video work, is unapologetic in its reclamation of female and feminized sensuality. In this piece, Minaya turns her body into one capable of returning any reductive gaze. Dressed in a white uniform like those worn by hotel maids or domestic cleaners, she appears at once as a laborer and an object of art. In a museum space, she paints a mural of stylized palm and fern leaves. Yet the red and blue foliage that blooms bears no botanic specificity. They function more as symbolic approximations for a generic tropical exoticism. In Minaya’s hands, these flourishes become tools to unpack how tourism and art media have long worked in tandem to flatten “the tropical” into aesthetic impressions, stripping it of historical or ecological depth.

Then, Minaya pours water over her body. Her uniform becomes soaked, clinging to her skin, and she begins to press, rub, and roll herself across the painted wall. The white fabric stains and smears with pigment. That white—symbolizing cleanliness, uniformity, and the erasure of individuality—becomes saturated with mess but also with presence. In this charged choreography, Minaya makes visible the invisible labor behind the illusion of paradise: usually women of color, tasked with maintaining order, beauty, and calm, while themselves erased from the picture. The artist refuses disappearance. She marks the surface and insists we see and feel her.

Siboney is also a meditation on diasporic endurance, as the artist’s uniformed body recalls the undervalued care and cleaning work performed by immigrant women across the United States. This connection is personal, yet no less political: Born and now based in New York, Minaya embodies a dual positionality she describes as “Dominican-United Statesian.” Her performance brings these geographies into contact. It tells how the sexualized, servile imagery long projected onto the Caribbean does not stay “over there” but migrates alongside bodies. The work is set to the enchanting melody of Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona’s iconic song “Siboney”—its eponymous title—in which longing for a beloved stands in for longing for home. Minaya employs its lyricism not to romanticize origin but to voice collective survival.

The piece asserts a new relation between subject and gaze, one that claims authorship and foregrounds labor. Minaya’s work does not reject beauty or sensuality as inherently exploitative. Rather, it wrests them from their commodified roles, making them sites of critique and subversion. In so doing, she balances aesthetic intensity with political weight, turning surface allure into a deeper reckoning.

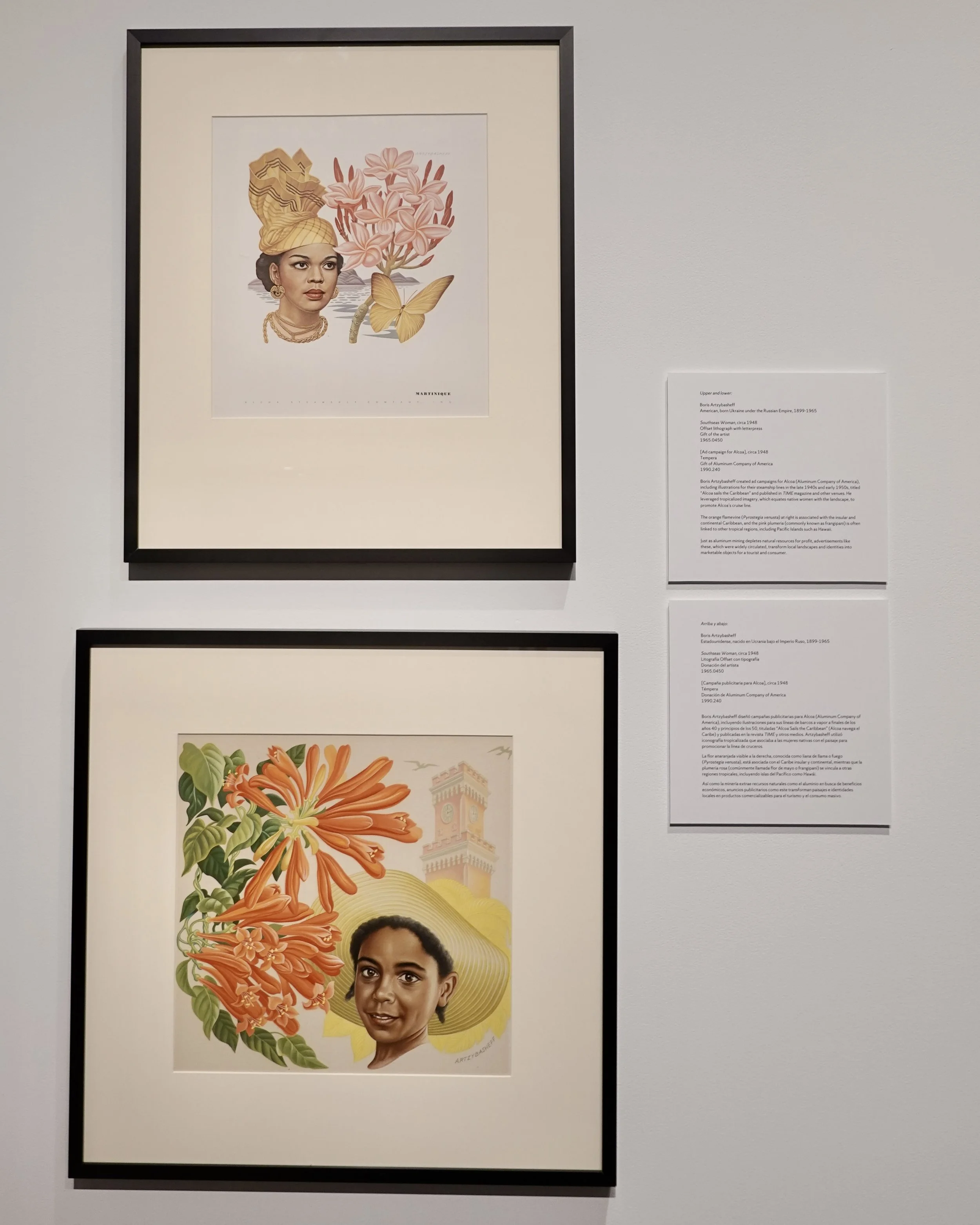

The exhibition, which Cristina E. Pardo Porto curated, also initiates a thoughtful dialogue between Minaya’s exploration of colonial visual culture and selected objects from the Syracuse University Art Museum’s collection. The carefully staged visual and thematic connections give form to what Nicholas Mirzoeff terms “countervisuality,” contesting the “unreality” produced by dominant ways of seeing.³ For example, two of Minaya’s prints—collages that combine contemporary postcards from Martinique with historical ethnographic photographs—speak back to illustrations from a 1948 Caribbean cruise ad campaign the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) launched. Both sets pair images of Caribbean subjects with tropical flora. Yet while the Alcoa ads project a sanitized, idyllic vision of the region as a tourist garden, Minaya’s jarring compositions reveal such harmony to be a constructed fantasy, which obscures the complexities and inequalities of Caribbean life.

Through archival photographs, prints, and stereographs from the 19th and 20th centuries, the exhibition’s geographic coordinates expand beyond the Caribbean islands to include Hawaii, Florida, and Central America. As Pardo Porto explains, approaching Minaya’s practice through what she calls “global tropicality” allows other bodies, landscapes, and histories to enter into the orbit of a broader visual cartography altogether. Within this framework, Minaya’s art reactivates the museum objects, prompting them to reveal the sociopolitical, cultural, musicological, and pedagogical narratives they have long carried—or withheld. In turn, they act upon the artworks themselves.

As viewers exit the exhibition, they once again pass the first work they encountered: #dominicanwomengooglesearch (2016). Suspended in midair, fragments culled from Google Images, interspersed with bits of tropical flora, drift gently with the movement of passersby. These floating pieces intersect with visual tropes visible throughout the exhibition, yet their fragmentariness resists cohesion. The hashtag in the title gestures toward visibility, toward the idea of a collective presence. Yet, it also signals the uneasy space between naming, seeing, and knowing, between image and identity. There is irony in the installation’s silent mobility: No search term, no representational frame, can contain the multiplicity of lived experience.

In this final moment, the work returns us to the exhibition’s central claim. It addresses us as not just viewers, but also consumers of a vertiginous contemporary visual culture, reminding us that seeing is never neutral. To unsee is not a simple rejection, but a recognition: of the gaze itself, and the uneven terrains it traverses.

The exhibition Joiri Minaya: Unseeing the Tropics at the Museum is on view at the Syracuse University Art Museum through May 10.

¹ In an interview with BAXTER ST, Minaya recalled how her interest in the tropical identity was sparked by an offhand comment from someone admiring her secondhand Hawaiian shirt: “Oooh, so tropical.” This moment prompted her to consider what the tropical really means, and how it functions as a cultural and aesthetic signifier.

² In her book An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Duke University Press, 2007), Krista A. Thompson examines the relationship between coloniality and visuality, focusing on the tropical contexts of Jamaica and the Bahamas. Postcards feature in Thompson’s analysis at various points throughout the book.

³ Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Duke University Press, 2011), 4-5.