'Mexodus' Spotlights Obscure Underground Railroad History

Hamilton changed the game for musicals, a fact that is evident with the newest hip-hop musical to hit New York: Mexodus. But instead of the story of the man on the $10 bill, Mexodus tells a story that hardly has widespread documentation. Brian Quijada and Nygel Robinson—the friendliest of emcees and the writers behind the musical—take the stage at Minetta Lane Theater each night to spin, spit, and speak the story of the lesser-known, south-bound Underground Railroad that ran into Mexico.

In the show’s first number, the duo drop some historical facts: Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, but it took the United States another 30 years to pass the Emancipation Proclamation, (and an additional two years for a nationwide enforcement of the proclamation). Today, historians believe that between 1829 and 1865, somewhere between 4,000 and 10,000 enslaved people fled to Mexico in hopes of finally being free.

“Did you know this shit? We didn’t know this shit!” Quijada and Robinson rap in the opening number.

Slave hunters caught some of these runaways; Mexicans who wanted the promised bounty for turning in runaways ratted out others. But there was a group that made it across and became community members in Mexican society, holding jobs and owning land.

Quijada and Robinson embody Carlos and Henry, respectively, two fictional characters who meet during this migratory moment. Henry is an enslaved Black man from Texas who is fleeing south after an altercation with the slave master on his plantation. Carlos is a Mexican sharecropper who is struggling with the guilt of deserting his compadres during the Mexican-American War. Both characters are wary of the other, but must rely on each other and form an unlikely alliance.

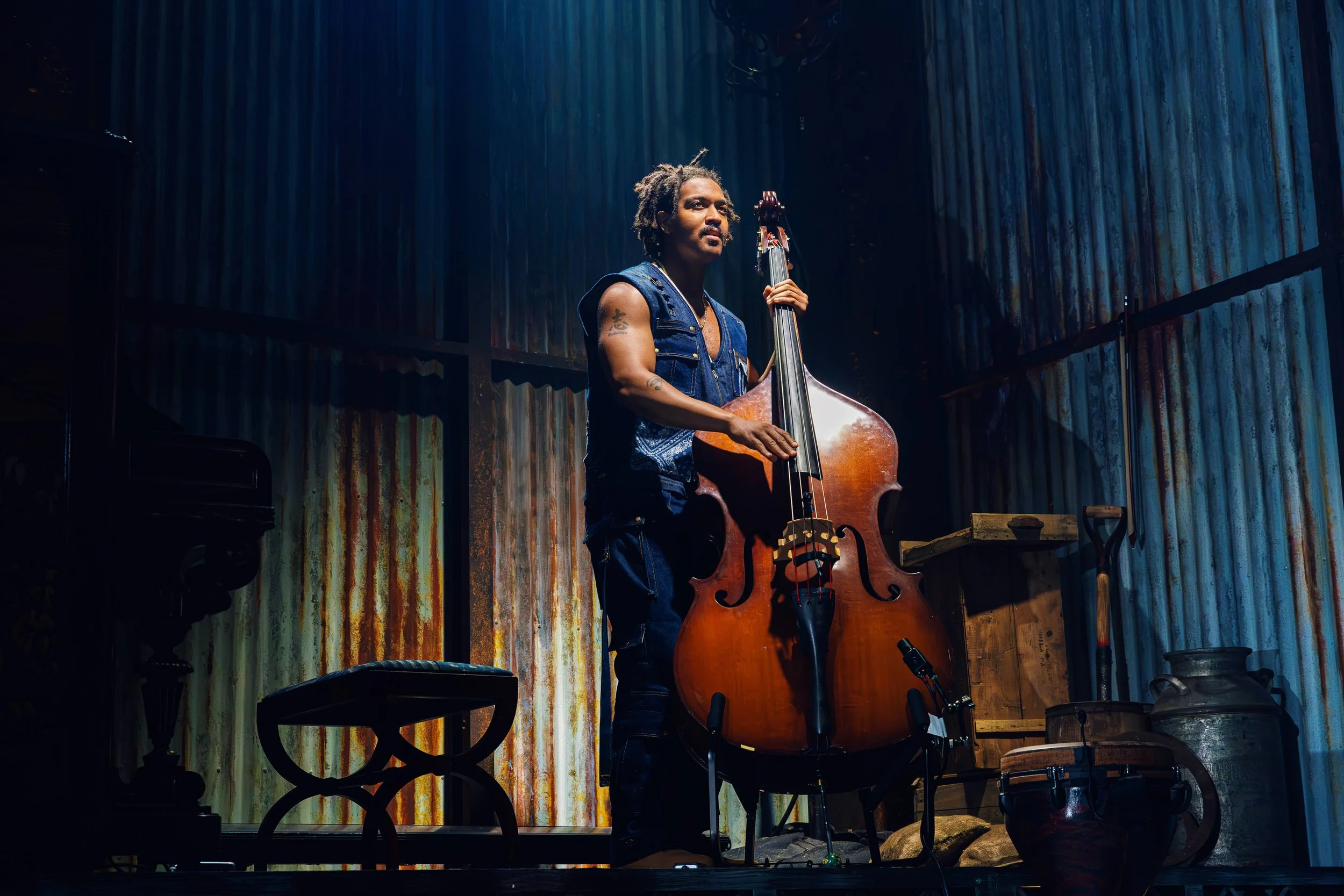

Most musical theater performances are an athletic feat, but this one, in particular, is akin to watching a marathon set to music. Calling it a “hip-hop” musical doesn’t do justice to the mixing and remixing of rap, R&B, gospel, and bolero that scores this show. And as if singing, dancing and acting wasn’t enough multitasking, Quijada and Robinson are also their own orchestra. With the stage outfitted in live microphones, the duo records and loops the sounds of them playing bass, keyboard, drums, or their own voices singing or beatboxing. One by one, they layer these instruments together to play intricate beats and melodies in real time.

There’s a playful, Rasquache element to this kind of storytelling—it’s DIY and scrappy—and frankly, pretty risky, particularly if the tech glitches. The live-looping technique also embraces the impermanency of live theater and the importance of oral history traditions. Instead of hitting play on a pre-recorded, instrumental track, Mexodus rebuilds a completely unique soundtrack each night, only to erase it and start again during the next show.

If not ceremonial, Mexodus is an ode to the oral storytelling traditions that have kept the stories of Black and brown people alive despite attempts to erase them from history. When passed down, oral histories can outlive people, papers, and physical archives. The DIY soundtrack, the intimacy of the Minetta Lane Theater, the intention and care behind each lyric makes the audience feel like they are in on a vital secret. Live theater is fleeting, existing briefly on stage and then lost into the ether. But in that loss, there is also protection; Mexodus invites the audience to be protectors of this hidden history and the people who descended from it.

Perhaps one of the most moving parts of the show is when Quijada and Robinson both drop their fictional characters and emcee personas and locate themselves in this history. Robinson takes a moment to acknowledge that his career as a performer is beyond what many of his ancestors—some of whom were enslaved—could ever imagine. He lists their names, determined to hold space for them every night. Quijada, who is Salvadoran-American, reflects on a childhood memory of his parents expressing fear when driving through a Black neighborhood in Chicago. “We are not born afraid; we are taught,” he says.

Using personal anecdotes, along with contemporary music and slang, is not just a Hamilton-esque strategy to translate historical facts and figures into our current day culture—the quick shifts blur the lines between the past and today. The story is reminiscent of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents who are patrolling the U.S.–Mexico border today or the ones who raided Canal Street to target African street vendors in late October 2025. “Black and brown bodies are still being hunted,” Quijada and Robinson rap near the end of the show.

Mexodus has been touring this past year, previously playing in Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Berkley. Its next stop is unknown, but I’d be surprised if this was the last we hear of the show. During its two-month off-Broadway run, it made a name for itself among the big leagues as NYC theater legends have been cycling through and singing its praises. The Color Purple’s Danielle Brooks and Hamilton’s Leslie Odom Jr. both paid a visit to the show. RENT’s Daphne Rubin Vega wrote “if I gave Michelin stars to the theater. THIS gets all three!!!” Even Miranda, who knows better than most what it means to make a successful hip-hop musical, posted to his Instagram account that “the outstanding musicianship . . . must be seen to be believed.”

Yet, Robinson and Quijada seem equally thrilled about audience members without Tony nominations. After bows at the October 24 show, Robinson waves for the soundbooth to cut the music. “There’s some woo-woo shit that happens here every night, a lot of ancestor veneration,” he says. ”And I just feel called to say this tonight.”

He tells us that he met an audience member before the show, “a 96-year-old young lady” who reminded him how important it is to listen to our elders while they’re still around. They’ve seen so much history, and made it through such difficult times already, he said. They have wisdom, hope, and humor.

“I don’t have my grandparents anymore, but if you do, please make sure to ask them their stories,” he tells the audience.

I text my abuelo on the way home.