On the Magic of Photography & Its Healing Prowess: A Conversation with Rafael Soldi

*The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—

Raquel Villar-Pérez (RVP): Can you tell me who you are, where you come from, what you do, how and when you decided to become an artist, and what the main topics are in your work?

Rafael Soldi (RS): I'm from Peru, born and raised in Lima. I relocated to the U.S. as a teenager. I didn’t always know I wanted to be an artist, but I knew I wanted to do something creative, and photography always intrigued me. I attended an all-male Catholic school in Peru, and the dynamics of masculinity were very charged and difficult for me to navigate. As a queer kid who spent a lot of time isolating from my peers, I could relate to the darkroom as a quiet, safe place to be with my thoughts. Many queer children use imagination and world-building as a coping tool, sometimes this involves magical thinking too. There was a small darkroom in my school, and it was magic to me—the process of creating worlds of my own with my camera and then watching them appear before me was a language I understood. I don’t really work in the darkroom anymore, but images remain at the core of my practice. My work centers on how queerness and masculinity intersect with larger topics of our time such as immigration, memory, and loss.

RVP: That’s a great response and really gives a fantastic overview to your background. How was relocating to Washington DC with your family and then deciding to stay and separating from them? What did you study at university and when did your career start shaping up as that of an artist?

RS: My father’s work with the Peruvian navy brought the whole family to D.C. and after a 2-year term it was time to return to Peru. I was finishing my last year of high school and had decided I would pursue art school. By then I also had come out to my family. With my parents, we decided that it would be best if I stayed in the U.S. I remember my mother telling me that—because of my queerness and my desire to be an artist—I’d be better off staying here. I’m really grateful for that experience and opportunity. Eventually I was accepted into the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) where I studied photography and curatorial studies. I loved my time there. The school was so well resourced compared to Peru and I feel like many of my peers took that for granted.

When growing up, I always felt like the world wasn’t built for people like me. Things really opened up for me in the U.S., but no matter what, there was still this lingering feeling that I was away from home. I had an unresolved relationship with Peru, now I understand that to be a sort of grief.

RVP: I can imagine it must have been brutal for you to realise that you had to stay somewhere whilst your family goes back 'home' because 'home' is not a place that would accept you. Your work Imagined Futures in a way reflects on the sense of migration, belonging, and what could have been. Can you tell me more about this project, when and how the need to address these topics came about, and how did you connect your lived experience with the universal experience of migration?

RS: It took me a long time to process what you mentioned above, this paradoxical relationship to “home.” At first there was some anger and denial, both a rejection of my home but also a protectiveness of it. Deep down I knew this was a core part of my identity but didn’t know how to contend with it. Over the course of 15 years, I felt sadness and longing and a haunting feeling that I really needed to resolve this. I am now just realizing these are the stages of grief. I hadn’t properly mourned that departure, that loss.

I constantly imagined what my life might have looked like if I had never left. And when I shared this with fellow immigrant friends, they immediately shared similar feelings. I called these “imagined futures,” and it struck a chord with me and others who had also had an abstract emotional relationship to this strange experience.

I also thought about the ways I imagined my future as a young person. I was aware of my difference from an early age, and I always knew that the acceptable options for me as a man were all incongruous to my way of relating to the world. I understood quickly that I was incompatible. So, there are these imagined futures too: the ones I imagined as a child, and the ones I imagine now. Imagination traveling from the past and from the future to converge on a point in time altered by migration.

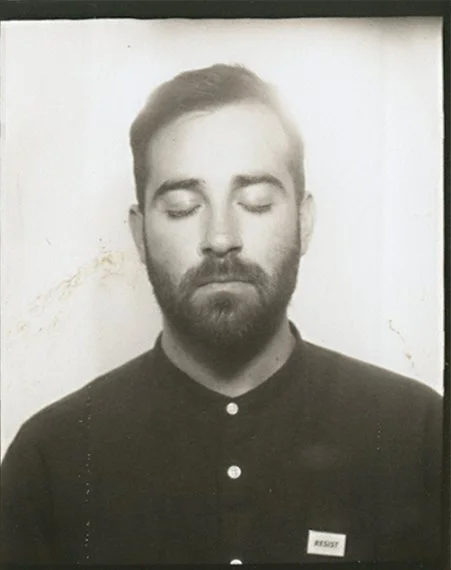

I decided to address these ideas through performance, ritual, and photography. Over the course of two years, I used photo booths, resembling the Catholic confessionals of my youth, as a stage for performative rituals and a witness to a farewell. I have had a complicated relationship to Catholicism, so this became a way for me to reclaim the experience of confession. Every time an imagined future visited me, I found an empty cabin in which to close my eyes, acknowledge its presence, thank it, and give it permission to leave. Through this process I was able to say goodbye again and again, and the repetitive action of acknowledgment, gratitude, and release became very healing. It was how I addressed this monumental and yet very ambiguous grief that I and so many immigrants experience.

RVP: Your project Entre Hermanos, also included in your current solo exhibition A Body in Transit at the Frost Art Museum expands from Imagined Futures by zooming into the experience of migration of the queer male identifying Latinx community. How was it to reach out to this community and get them excited about participating in the project, and what did it mean for them and you as a community to come together and share your own experience and ‘imagined futures’?

RS: My intent is always to use personal narratives to create a language that others can relate to. When I completed Imagined Futures, I immediately knew that there was an opportunity to share this framework for grieving with other people with similar experiences. I worked with an organization in Seattle called Entre Hermanos, founded during the AIDS crisis to provide services to Latinx LGBTQ community.

Through them I invited male- and queer-identifying Latinx immigrants for a collective moment of discussion and reflection. We facilitated a private conversation around how each perceived their future as young people in their countries of origin, and how that perception may or may not have changed over time. We continued to reflect on the role of imagination for queer Latinx people, and how we could reimagine our pasts and futures today. It was an emotional evening, with varying levels of acceptance, forgiveness, and grief, as well as stories of rebirth, transformation, and resilience. Each participant was then invited into a photobooth that I built, asked to close their eyes and hold a shutter release while I walked them through a deep meditation. At any point during this quiet, intimate time, the individuals were able to make a self-portrait if they desired.

RVP: These two projects, Imagined Futures and Entre Hermanos, are portraits and the subjects appear with their eyes closed. Can you tell me more about this choice?

RS: The closing of the eyes was an intuitive choice at first. It just made sense to me, this was an internal process, a ritual. It was also a strategy of refusal. The eyes are often the way we connect to portraits, and by closing them I am turning the viewer away from an internal world, forcing them to use their own imagination and look inward into themselves.

Curator Miguel A. Lopez put it beautifully in his essay in my book. He wrote, “Each photograph has a ghostly quality, as if his body were both present and absent. What is truly important about this work will not be found in what we see—in the photograph—but in his private reunion with himself, to which we are but distant, mute witnesses. This simple act of not looking into the camera’s lens perverts the intended function of the traditional ID photo, symbolically refusing to be defined by that homogenizing form of representation and its commitment to surveillance. Through this archive of photographs of his own motionless body, Soldi not only expresses his own personal grief; he also describes a shared mourning for all that we are often forced to leave behind—a land, a family, a language—in order to be able to keep living.”

RVP: Your next project, CARGAMONTÓN, has a very different approach, where we can see intertwined bodies and limbs, with no frontal faces. Can you tell me more about CARGAMONTÓN and your process for this project?

RS: CARGAMONTÓN naturally developed from these earlier projects. I started thinking a lot about the all-male Catholic school I attended most of my life, and how much it influenced me and the boys around me. It was a hotbed for toxic behavior and now I look back at it as a laboratory for understanding masculinity.

CARGAMONTÓN is a portfolio of eight aquatint photogravures probing masculinity, intimacy, violence, and rite found in adolescent horseplay that hovers between bullying and homoerotic self-discovery. It began with the memory of a “game” we played in the school yard named “Cargamontón” (which translates to gang harassment). The object of the game is to wrestle a boy to the ground, and then bury him under a pile of classmates’ bodies. It was a form of bullying, of exerting power over that one person, of humiliating him. I’m interested in the vehicles boys create to access touch and intimacy. As someone who was teased for being gay and a frequent victim of this action, I both resented the humiliation and welcomed the opportunity to be entangled with the bodies of other boys. I knew that homosexuality was considered unnatural, and therefore I felt the price to pay for intimacy was violence. Now I understand how isolated all boys are from touch, and I see these rituals as mechanisms for asserting power and masking desire, as part of a larger exploration of masculinity in Latin America.

I began by accumulating an archive of found videos that Peruvian teens engaged in this game posted on the Internet. I then selected stills, which were transformed into enormous copper etchings with which we made beautiful prints through the aquatint photogravure process, merging 21st- and 19th-century processes. The result is a series of images akin to obscure memories that depict bodies vacillating between torture and pleasure. My intention is to place the viewer in the position of having to decide whether they’re witnessing violence or playful intimacy.

RVP: I find it very interesting how you describe this situation of violence and expand on its ambivalence. I read a paper where the writer argued that teenage bullies become so because of how ambivalent they are regarding expectations from adults and society at large; they desire something because it is what they’re told they should wish, and at the same time they rebel against it. In societies where toxic masculinity prevails, I imagine there will be many teens struggling with the aspiration to become and perform the idea of ‘macho’ within the society’s imaginary. Do you think is this the case? Do you think Latin American societies are changing to this?

RS: Absolutely, this is true. I think the obsession with projecting a certain masculine image is the product of a paradoxical relationship to it. There is both a pressure—from society, the media, friends, religion, fathers, and mothers—to perform and embody this identity, and at the same time a deep sense of loss of who we were before we were told how to be a man. So we embed our own rebellions into the system. There is a great artwork by Barbara Kruger, it shows a group of men brawling in suits and over it the words “You create intricate rituals to touch the skin of other men.” That’s it, essentially—we lean on these systems of violence and aggression, which affirm our masculinity, to legitimize our desire for intimacy. We take opportunities for touch and connection and turn them into power struggles so we can say, in the end, that we were just trying to prove who was more of a man. That’s why often the most charged arenas of masculinity also tend to be the most homoerotic.

I should clarify a few things here. First, masculinity is not a monolith. Masculinity isn’t inherently bad; it is simply a fact of life. Bell Hooks’ book The Will to Change does a great job in explaining the importance of looking at masculinity critically through a feminist lens. Hooks says that the real issue is the system that produces patriarchal masculinity. It’s important to shift how we think about men who participate in patriarchal masculinity—not to think of them as just abusers and bullies, but to think of them as victims of the patriarchy. We must understand that we are all born free of these concepts, and at a certain age someone decides that the time has come to “act like a man.” That child is now a victim of patriarchal masculinity.

I do think Latin American society has made big strides in the right direction. Sadly, at its core, we’re still governed by very traditional values. I like to point both of these realities out because I’m aware that my work focuses primarily on my experiences during my school years, in the ‘90s and early ‘00s. My understanding is that things are quite different now in many ways, and I’ve seen many of my heterosexual childhood friends develop caring, intimate relationships with one another that stand for a beautiful and honest version of masculinity that requires a real investment in authenticity. At the same time, I’m amazed at how little things have changed. I still encounter very toxic views, and it’s like whiplash! The patriarchy is alive and well.

RVP: Lastly, are there any new projects you’re working on? When should we expect to see some sneak peeks of them?

I am preparing for a solo exhibition at the Frye Art Museum that will open in October 2023. The centerpiece of this exhibition will be a large-scale, 4-channel video work expanding on my exploration of masculinity in Latin America, through the lens of my school memories. The film will follow a group of uniformed school-aged boys as they perform a series of rituals in a black box theatre, thus revealing the absurd nature of the architecture of masculinity once removed from its context.

I’m also working on a new series of text works exploring language and bilingualism. These are in early stages, but they use humor, queering, mishearing, journaling, translation, and word construction/deconstruction to reveal the liminal space between languages that many immigrants find themselves in.

—

A body in transit is on view at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum from August 20, 2022 to December 4, 2022.

Raquel Villar-Pérez is an academic, art curator, and writer interested in post and decolonial discourses within contemporary art from the Global South, mainly from Africa, Latin America, and their diasporas, and how they navigate and resist the trends set by Globalization.

Her work focuses on women's experiences and notions of transnational feminisms, social and environmental justice, and how these are presented in contemporary art.