Revisiting the Afro-Cuban Syncretism of “Orisha/Santos”

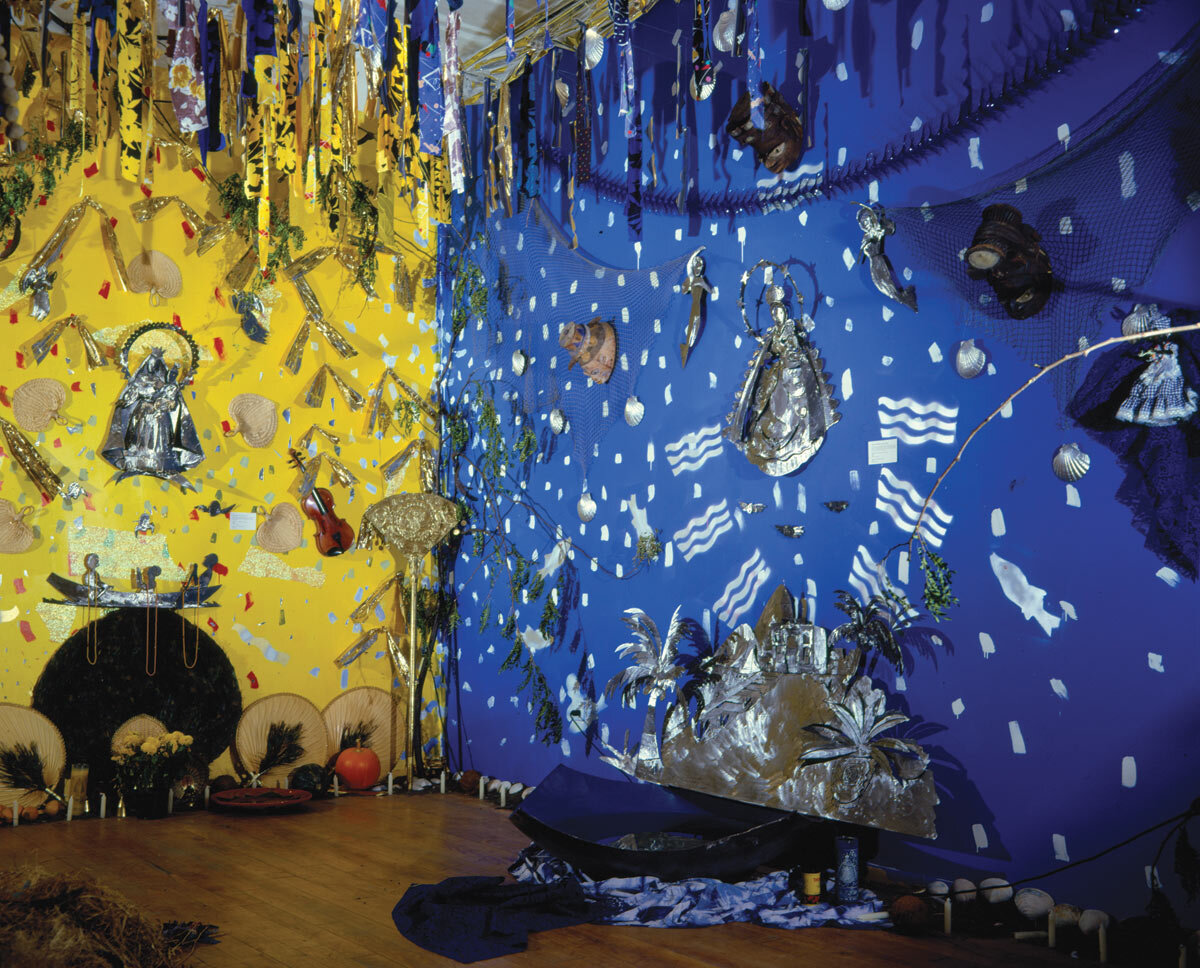

Thirty-five years ago, it would have been difficult to imagine the level of mainstream representation that Yoruba deities now enjoy in art, music, and film. From the Marvel universe to Beyoncé, this visibility has necessitated—for better or worse—the kind of formal introduction to the significance and meaning of the orishas that “Orisha/Santos: An Artistic Interpretation of the Seven African Powers” anticipated when the exhibition opened in the fall of 1985 at the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Arts (MoCHA) in the SoHo neighborhood of Lower Manhattan. Featuring a series of eight steel sculptures by Puerto Rican-born artist Jorge Luis Rodriguez along with accompanying orisha altars by Harlem-born artist Charles Abramson, the installation was at the time, “a pioneering exploration of the hybrid nature of Afro-Caribbean belief systems,” in the words of then-chief MoCHA curator Susana Torruella Leval.

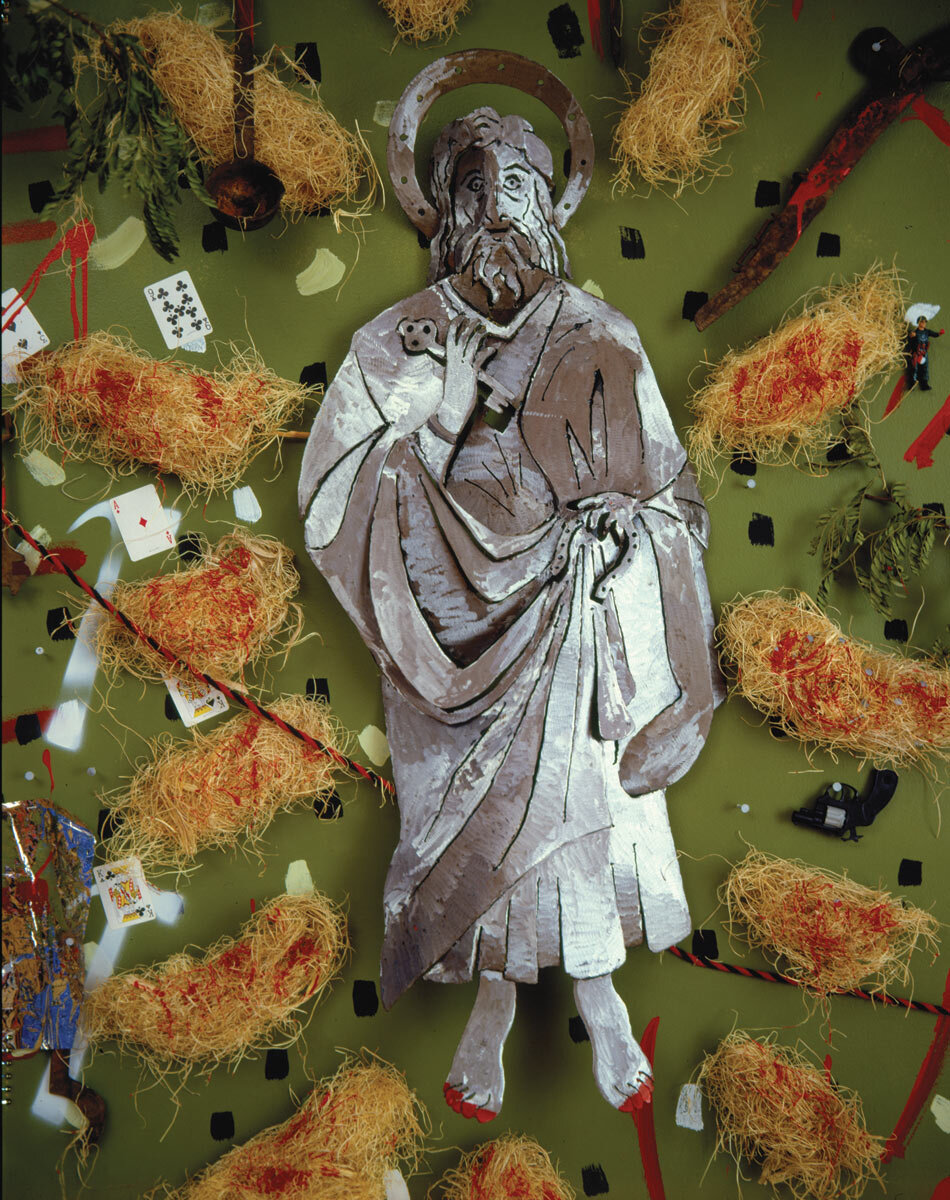

Central to this prescient aestheticization was the diasporic syncretism of Afro-Cuban Santería (alternatively known as Lucumí or the Regla de Ocha), understood for its coded blend of elements from the Yoruba religious and spiritual tradition in West Africa and holy figures from Roman Catholicism. As such, each of Jorge Luis’s Catholic saint sculptures offers subtle, yet figurative reference to their orisha counterpart, with Abramson’s elaborately crafted altars only deepening the allusion.

During the mid-1980s, as new institutions like MoCHA, Just Above Midtown Gallery, The New Museum, and The Studio Museum in Harlem resisted the traditional gatekeeping of the art world by catering to an emerging, multicultural cohort of artists; Jorge Luis and Abramson went one step further by eschewing contemporary art’s secular modernism in favor of religious iconography and spiritual themes. The two artists, who had met years earlier, became close collaborators while sharing a residency with David Hammons at the original Studio Museum in Harlem, before the institution moved to its present-day location.

Despite the perceived liability in subject matter, the exhibition was in the vanguard for its acknowledgment of the diasporic religious communities that had become firmly rooted to New York City’s cultural landscape in the decades prior. Moreover, the recent arrival of Caribbean im/migrants also coincided with a growing interest among Black Americans in Afro-Caribbean spiritual practices and African-derived cultural traditions.

Born and raised in Harlem to parents originally from St. Croix in the Virgin Islands, Abramson was in fact an initiate into the Yoruba priesthood, having achieved the rank of Babalu-aiye. His contribution of orisha altars, with offerings of food, flora, and other recycled materials, embodied the living character of each of the Yoruba deities disguised as Catholic saints, while also alluding to the formerly industrialized character of the surrounding neighborhood where the exhibition took place. Fellow Santería initiate Cynthia Turner, in turn, would provide catalogue descriptions of each orisha, as well as an introductory essay to the Seven African Powers. Known in Spanish as “Las siete potencias africanas,” as Turner explains, these seven orishas, on which the exhibition was based had become the most popular and enduring among Yoruba religious practitioners in the “New World.”

Jorge Luis, in turn, engaged in the art of santo-making, a centuries-old Puerto Rican tradition of carving wooden statuettes into Catholic figures; thereby making him a “Santero” as well, albeit in the literal sense and using metal sheeting in place of wood. Much like the familial structure within Santería in which communities of practitioners belong to houses, groups of Puerto Rican artisans, as Toruella Leval explains in the original exhibition catalogue, developed familial styles that differentiated the practice from the Spanish Baroque and Spanish colonial tradition which had taken hold throughout the Americas. Toruella Leval notes that in Puerto Rico, Santos were seen as “humble intermediaries between God and man.” She continues:

“They might be asked to intercede to save a life, cure an animal. Bring rain, find a novio or lost earring. In exchange, they were prayed to, loved, trusted, and given a new coat of paint in celebration of their name day.”

It should be noted that around the same time of the exhibition, the wooden figures had achieved some notoriety outside of the Island as an object of desire among collectors of rare and antique crafts.

While his process was informed largely by a more anthropological approach, Jorge Luis was also inspired by his childhood in his native Puerto Rico, where he experienced spiritual encounters at an early age and took frequent trips to neighboring Loíza to observe firsthand some of the African-derived cultural traditions and religious festivals, which date back centuries to when freed or escaped African slaves first settled there. In addition to the Seven African Powers, Jorge Luis chose to depict the crucifixion. Though in the Yoruba belief system God, the creator does not, as Turner explains, take human form, the figure of Jesus Christ can be associated with several orishas in the “New World” context.

Famed Yale art historian Robert Farris Thompson, just one year removed from releasing his landmark 1984 tome Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, also contributed to the original exhibition catalogue, which was updated in 2012. In his essay, he places Jorge Luis and Abramson at the vanguard of what he terms, “New York Afro-Catholic consciousness,” while noting the attention to detail present in the work of both artists. For example, Jorge Luis’s interpretation of Elegua (or El Niño de Atocha) dancing on one foot, according to Farris Thompson, can be traced back to the southern Egbado (now Tewa) tribe and symbolizes “the breaking out of an argument and dissension, not to be ended until Elegua has placed both feet on the ground.” Abramson, in turn, surrounds the Yoruba deity with what Farris Thompson perceives as an unconventional altar, one that features candy and other items alluding to the childish nature of Elegua. “Whenever we are childish,” he writes, “we stand on Elegua’s single dancing foot.”

Ultimately, “Orisha/Santos” offered non-practitioners and practitioners alike with a neutral space for the universal experience of transcendence—far removed from the criminalized and fetishized history of Afro-Caribbean syncretism, which continues into the present. Torruella Leval, in a reflection published in the updated catalogue, remarked that “visitors crossed the thresholds between the sacred and the secular, the spiritual and the sensuous.”

After its closing in October of 1985, “Orisha/Santos” would be added to the World History of Art, thus ensuring a measure of notoriety and recognition of the exhibition. Abramson would pass away suddenly in 1988 after a brief, undisclosed illness, leaving behind an artistic and cultural practice that highlighted the fluidity of African traditions and their diasporic manifestations. Jorge Luis would honor this legacy by channeling Abramson’s spirit to complete a series of installations entitled, ''The Bending of Osa Nyin,” designed by the late artist. This year also marks the 35th anniversary of another landmark installation by Jorge Luis, entitled “Growth,” which officially inaugurated New York City’s Percent for Art Program. He resides in Brooklyn with his wife Evelyn, where he continues to work out of a home studio.

To learn more about his work, visit: https://jorgeluisatelier212.com/orisha/

Author’s Note: Special thanks to Andrew Viñales, Jorge Luis Rodriguez, Evelyn Rodriguez, Arlene Dávila, Janel Martinez, and Diana Ramos-Gutiérrez for their support.

Néstor David Pastor is a writer, editor, and translator from Queens, NY. He is the founding editor of Intervenxions, a Latinx arts and culture publication of the Latinx Project at NYU, and Huellas, a bilingual magazine featuring long-form writing by emerging Latin American and Latine writers. His past editorial work includes the award-winning NACLA Report on the Americas, a print magazine by the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), and CENTRO Voices, a digital publication of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. He is the editor of Latinx Politics–Resistance, Disruption, and Power (2020), Intervenxions Vol. 1 (2022) and Intervenxions Vol. 2 (2023). In 2022, he was the recipient of the Queens Arts Fund ‘New Work’ grant. Most recently, he was selected to participate in the 2023 NALAC Leadership Institute. An essay on Cayman Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art is forthcoming in Nuyorican Art: A Critical Anthology (Duke University Press, 2024). To see his full portfolio and current projects, visit: www.ndpastor.com

Jorge Luis Rodriguez received a BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 1976, and an MA in Sculpture from NYU in 1977. His work has been featured in one person shows at Just Above Midtown Gallery, NYC; Cayman Gallery, NYC; and at the Altos de Chavon, La Romana, Dominican Republic; and the Art Gallery at Kingsborough Community College, CUNY. He has participated in group exhibitions at OK Harris, NYC; Greene Gallery, NYC; The Whitney Counterweight Auction, NYC; Centro Internazionale Della Arti e Del Costume, Venice, Italy; Franklin Furnace, NYC; Equitable Gallery, NYC; Kozel Castle, Galerie Behemot and Manes Gallery, all in the Czech Republic; The Studio Museum of Harlem, NYC; Yale University, New Haven, CT; Museo de Arte e Historia de San Juan, San Juan, Puerto Rico; Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA; El Museo del Barrio, NYC; PS 1, NYC; Maryland Art Institute, Kenkeleba Gallery, NYC; and at the Goddard-Riverside Community Center, NYC. Jorge Luis has been the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Creative Arts Programs Services Sculpture Fellowship, a NY State Council on the Arts Artist in Residence, and an Artist in Residence at the Studio Museum of Harlem. He received a commission from the NYC Board of Education in 1992 to create, “The Tree of Knowledge,” a permanent sculpture at PS 128 in Washington Heights, and was the first artist to install a permanent sculpture (“Growth,” East Harlem Art Park) under the auspices of the NYC Percent for Art Program.

Charles Abramson studied at the Printmaking Workshop and at the Art Students League, both in NYC. His work has been featured in one person shows at Just Above Midtown Gallery, NYC; Cinque Gallery, NYC; Watts Towers Arts Center, Los Angeles, CA; and at Two Raw, NYC. He has participated in group exhibitions at The Studio Museum of Harlem, NYC; The Henry Street Settlement, Abrons Arts for Living Center, NYC; Pleiades Gallery, NYC; National Theater, Lagos, Nigeria; New York State Office Building, NYC; The New Museum, NYC; PS 1, NYC; Fashion Moda, NYC; Wake Forest University Galley, Winston-Salem, NC; Franklin Furnace, NYC; Rotunda Gallery, NYC; and at Kenkeleba Gallery, NYC. Charles has been the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship; a Creative Artists Program Service Sculpture Fellowship; and an Artist in Residence Fellowship with Jorge Luis Rodriguez and David Hammons at the Studio Museum of Harlem.