Rigoberto Torres: The Puerto Rican Body as Archive

From Paleolithic figures to Renaissance anatomy studies, the body has always been central to art—a site where knowledge, identity, and spirit are inscribed into flesh and form. It is the vessel for our essence, our ashé, and the embodied wisdom we carry, whether we validate this scientifically through mitochondrial DNA or spiritually through the presence of ancestors and the cuadro espiritual that guides and protects us.

Beyond flesh and bone, the body is a repository of memory and experience, a terrain where survival, intimacy, and selfhood are continuously negotiated. Fleeting yet resilient, vulnerable yet persistent, the body bears witness to violence and joy, pain and exaltation, healing and surrender.

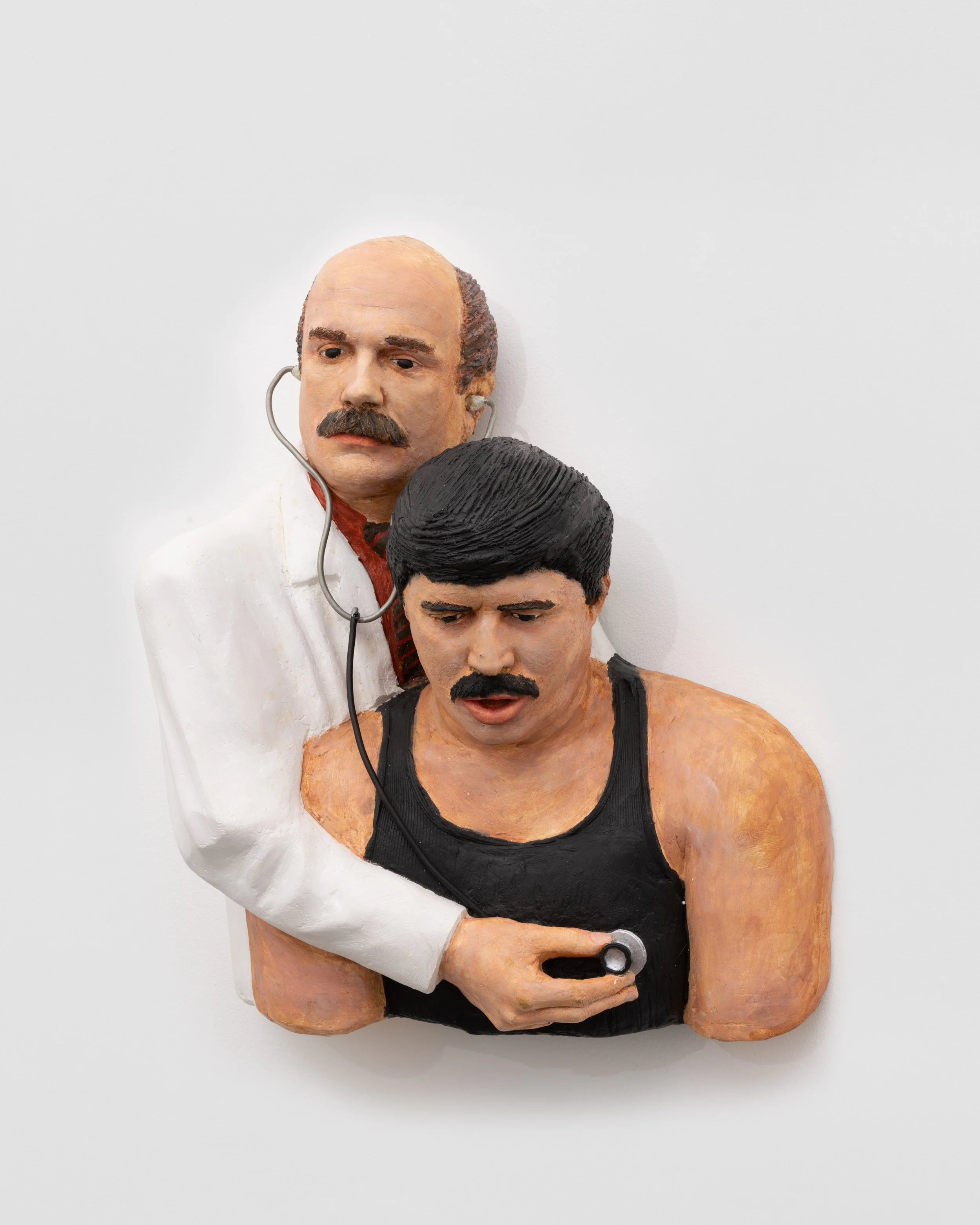

Over decades, Rigoberto Torres has cultivated a practice attentive to material intimacy and the enduring presence of the human form, applying techniques first learned in devotional casting to honor the lives and gestures of everyday Puerto Ricans.

In collaboration with sculptor John Ahearn, a creative partnership spanning four decades, Torres transforms the body into a living archive, where each curve, posture, and breath captured in plaster memorializes human encounter—both communal and deeply personal.

“When I met Rigoberto, I knew right away he was exactly who I was looking for—someone I could work with, trust, and who could help me understand things more deeply,” Ahearn tells me in an interview. “He is the most serious, sincere, open, and dedicated person I’ve ever met. Whatever I saw in him back in 1979—in 40 years I would see it doubled.”

Rhina Valentín, a multi-hyphenate artist known as “La Reina del Barrio,” recalls being immobilized beneath layers of plaster, suspended in a transcendent, liminal space during a 40-minute life-casting session with Torres and Ahearn in 2023. Today, she reflects with pride on the result of her experience: Crown #3 has entered El Museo del Barrio’s collection, as did Crown #2 at the Bronx Museum, both realized through Torres’s care and artistry.

“Seeing the works through their eyes gives me fresh eyes on my own art,” Torres says. “Getting to know someone truly takes time, and each person I have cast becomes part of my family, holding a special place in my heart. The bond between artist and participant is unique, built on trust, care, and shared experience.”

He also shares the artwork. “When I make life casts, I believe each participant should have a sculpture for themselves,” Torres says. “Each piece that we gift back is special: painted with love, handled with care, with attention to hair and skin tone.”

The care begins at the very start and continues through every step of the casting process, so that the participant receives something made with respect and thoughtfulness.

“I typically make three originals: one for the participant, one to support ourselves as artists, and one to exhibit or loan for exhibition,” he says. “These are always limited editions—never more than three. This is not a factory; it is a practice of care.”

Through his life casts, Torres ensures Puerto Rican presence, memory, and stories endure. Even hidden wounds mark the geography of memory, where survival is quietly preserved.

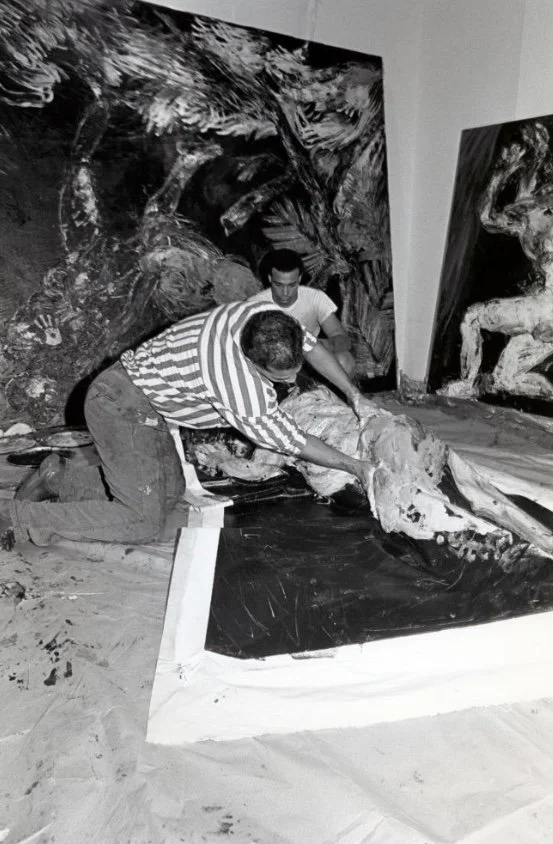

Born in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, in 1960, Torres moved to New York City as a child, settling in the South Bronx. There, he apprenticed in his uncle’s religious statuary workshop, learning to mold and cast saints and devotional figures—skills that would later inform his life-casting practice. In 1979, while still in high school, Torres met Ahearn at Fashion Moda, a South Bronx gallery that bridged high and low art, fostered hip-hop and graffiti, and nourished the borough’s inimitable, unfolding cultural scene. Their relationship quickly became one of deep collaboration, rooted in trust, shared labor, and mutual recognition of each other’s artistry.

“Seeing Rigoberto’s work presented and highlighted does a world of good for me because I care so much about him,” Ahearn reflects in an interview with BronxNet. “I see how good he looks in the show.”

The two artists have represented the people of the South Bronx in exhibitions worldwide. Increasingly, exhibitions illuminate Torres’s role not simply as collaborator but as artist and cocreator, whose work embodies vision, agency, and the materialization of Puerto Rican life on the mainland and the island.

As guest curator Christian Viveros-Fauné explains to me while discussing the We Are Family exhibition, slated to run from October 1, 2026, to January 10, 2027 at The Bronx Museum of the Arts, “Rigoberto is one of the few artists in America who has managed to combine ideas around art, the art gallery, the neighborhood into a simple declarative sentence: Advanced art is for everyone.”

He appeared at the XLV Venice Biennale with works such as Julio, Jose, Junito (1991–1992) and Margaret and Ervin (1992). When the exhibition Swagger and Tenderness opened at the Bronx Museum in 2023, it addressed a long-standing imbalance, finally recognizing both artists on equal footing. Cocurators Amy Rosenblum-Martin and Ron Kavanaugh focused on Torres’s work, highlighting it with care and context. “Torres’s quiet leadership in socially engaged art practices has inspired many artists and the art world in general, including me,” Rosenblum-Martin says to Hyperallergic.

In the same article, art writer Angella d’Avignon writes, “When presented side by side, it is ultimately Torres’s sculptures that stand out . . . Torres is radiant.”

The impulse to inscribe memory, presence, and identity runs deep in Puerto Rican and Caribbean history. Taíno and Igneri traditions used pigments like achiote, wild indigo, and jagua fruit (Genipa americana) to create vibrant body markings, with tattoos and piercings signaling lineage, affiliation, and spiritual meaning. In a conversation, arteologist Diógenes Ballester—a scholar, artist, and philosopher—observes that these deliberate markings turned the body into both living text and protective shield.

Contemporary Puerto Rican artists continue this trajectory. As Ballester reminds me, while in Korea, Marcos Dimas, cofounder of El Taller Boricua, learned the technique of frottage—rubbing carved stones with dry ink to achieve their imprint. Martín “Tito” Pérez used his body in frottage, creating una impresión de su cuerpo en lienzo. Likewise, at EFA Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, Nicholasa Mohr pressed her torso onto a plate prepared with cera blanda (soft ground), then submerged it in acid; when the plate was cleaned and printed, what remained was the trace—la huella—of her breast.

The late painter Arnaldo Roche Rabell also embedded ancestry and memory into matter, saturating canvases with pigment while tracing the contours of live models beneath. His meditative, tactile process—often in collaboration with his mother, María—produced works that fused body and spirit. Paintings such as The Origin (1986) and The Kiss (1988) entwine her figure with Puerto Rican flora, merging rebirth, intimacy, and ancestral presence into corporeal form. Christina Córdova sculpts her daughter Eva in unglazed clay, converting the island’s material and symbolic essence into bodily form. Mónica Félix interrogates the colonized and contested female body through photography, video, and installation. Today, Boricua youth carry forward these traditions through tattoos inspired by Taíno and other Indigenous Caribbean symbols, tracing ancestral presence on contemporary flesh. Across media and generations, the body remains a living ledger, inscribing memory, lineage, and cultural survival.

Life casting carries a history as rich as it is varied: from ancient Egypt and Rome, where death masks preserved likeness and spirit, to the Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, when artists and anatomists employed plaster and wax to study the human form. The practice flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries, and in the 20th, George Segal’s plaster figures captured the rhythms of everyday life with haunting immediacy.

Torres’s contemporary practice threads through this lineage, transforming an ancient and modern tradition into a vessel that immortalizes the Puerto Rican body and culture, creating a living archive that honors neighbors, family, and community for their vibrant, grounded humanity. His sculptural kin shine—shaped and held in memory, in the rhythms of daily life, and in the traces of ancestral practice—enduring as luminous testaments of presence and continuity.