Seeds of Colonialism: Ohio Forces in Puerto Rico

Theresa

I moved from New York City, my hometown, to Cleveland, Ohio in 2004 when I accepted a teaching position in the School of Art at Kent State University. At the time I was entering a new phase in my life, and the move afforded me the opportunity to broaden the scope of my teaching and artistic production. It would take several years before I understood the true significance of the move, however, and how it provided the footing for a monumental shift in the conceptual development of my creative process following the untimely death of my mother Theresa in 1999.

Theresa was the second oldest of six daughters born to my grandparents Ruperto and Emilia in 1927, just six months before they emigrated from Puerto Rico to New York. The Puerto Rican family typically revolves around the matriarch of the family, and as her daughters began to marry and nurture children Emilia would organize gatherings every Sunday and cook traditional meals for a burgeoning group of fifteen grandchildren. Following my grandparents’ passing, the sisters continued this tradition and over the course of many years joyfully assembled in the kitchen to cook elaborate dinners and celebrate the many milestones of a large family.

The loss of Theresa after 48 years of marriage was a crushing blow for my father Benito. When I spent time with him during his initial grief, I would find him poring over old black and white photographs of their courtship in the Bronx in the late 1940s, and then working to safeguard and organize old photographs of our Puerto Rican ancestors before and after they emigrated to New York in the 1920s.

Throughout my life their collection of photographs would occasionally surface at family gatherings, but to see them again as my father dealt with his grief was a critical turning point. As a second generation Puerto Rican born and raised in the continental US, I suddenly found myself revisiting an unresolved relationship with my culture and coming to terms with the harsh realization that I would no longer absorb our family history through my mother’s voice. I now viewed the survival of these stories and images, of the hardships they endured to establish themselves in the Bronx after leaving Puerto Rico, as paramount to the next generation and I began to wonder how they would be preserved and passed on.

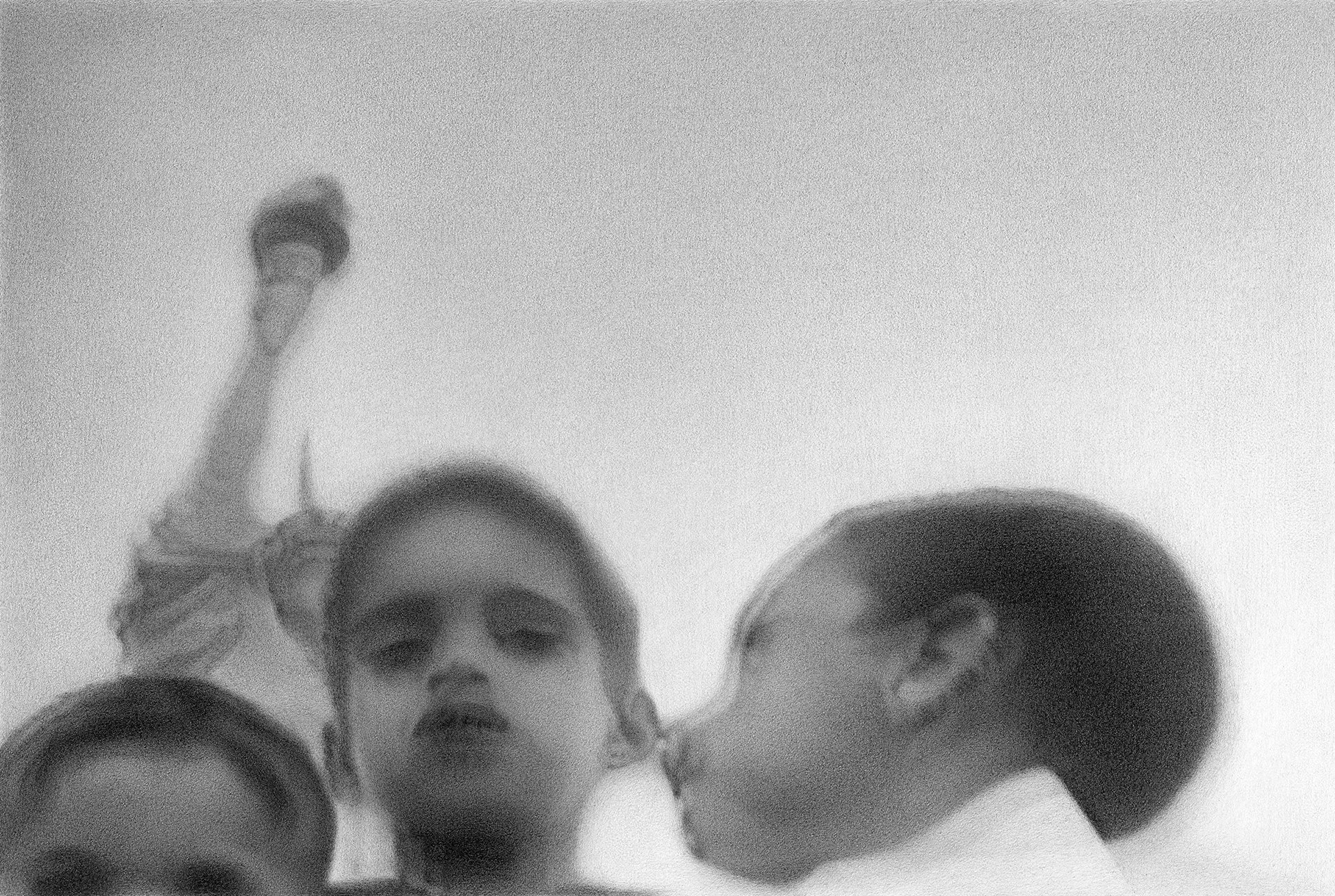

In 2000, I began a series of elaborate drawings based on these photographs. I sat for months with each drawing, and through the meticulous replication of a photograph I spent hours processing my grief and trying to restore the context of the story behind a depicted event. As a formalist, I also contemplated the drawings as a meditation on the inherent nature of abstraction in photography. I became intrigued by how the diffuse quality of the photograph, translated into a drawing with a ‘sfumato’ effect of layered graphite, played with the viewer’s initial perception of the image and demanded scrutiny. The viewer felt compelled to comb the surface of the work in disbelief at its function as a drawing, and this act ultimately brought the viewer’s full attention to the image’s subject and content.

Ruperto

Drawing as a medium has always played a prominent role in my work and it has continuously steered me toward important shifts in content and media. When working on the second drawing in the series, I began to think of the drawing’s title, Ruperto, as the first chapter heading for a narrative about my ancestor’s history.

Delving more deeply with time into my family’s movie archives I became enamored by spontaneous expressions and movements that were passing in front of my father’s 8mm movie camera, and in 2009 created a sequence of five drawings from captured film stills titled Liberty Island. They contributed to the narrative by depicting my three brothers and my mother positioned before the Statue of Liberty in 1958. It presents my father’s guileless perspective as a young Puerto Rican viewing the statue through the lens of his camera’s viewfinder—appreciating the statue as a universal signifier of democracy, freedom and the United States. I, however, as the second generation with seasoned eyes, view Liberty Island through the repercussions of change. The promise of the New Deal in the US and Operation Bootstrap in Puerto Rico in the 1950s had reached its pinnacle and was in rapid decline as we entered the 21st century. Liberty Island, created eight years after 9/11 and nine years before Hurricanes Irma and Maria, is now radically repositioned through the lens of our current border policies and the resurgence of political ideologies that undermine our humanity.

Displacement that leads to assimilation is most destructive when the language is lost, and the next generation is unable to communicate with relatives to understand the breadth of their history and culture. For much of my early adult life I experienced a tremendous amount of internal conflict and guilt for not learning to speak Spanish after my mother attempted to teach me as a child. It felt as though I was living multiple lives, adhering to Christian doctrines while surrounded by the American counterculture of the 1960s, the heyday of Rock and Roll, and returning home to the traditions of my Puerto Rican heritage: its food, music, dance, warmth and many family gatherings. It was difficult to maintain a sense of deep connection with my culture while dealing with the pressure to fit in.

As I became more involved in an exhaustive examination of my family history, I became increasingly haunted by images of my grandfather and my memories of him when I was a six-year-old child. I wondered who was this man, a pioneer, who emigrated to New York from Puerto Rico with his wife, two infants, and extended family in 1927? Who was this man who settled down to become a community activist in the Prospect Avenue-Longwood section of the Bronx, a publisher of Spanish periodicals, while raising six exceptional daughters with my grandmother?

In an effort to draw parallels between the past and the present, in 2013, I decided to use a single-lens reflex camera with a digital-imaging sensor to capture high definition footage of neighborhoods in New York and Puerto Rico where my ancestors had lived. I was able to use this highly adaptable tool to effectively film areas of the Bronx where my family settled and in municipalities in Puerto Rico where my maternal grandparents were raised. Eventually, I discovered a letter by my grandfather Ruperto Undenburgh published in an anthology of Hispanic literature (Herencia: The Anthology of Hispanic Literature of the United States, 2001). It was shocking to encounter for the first time his voice denouncing the US government’s mismanagement of Puerto Rico and questioning their presence on the island. “Open Letter to a Libelist” was originally printed in the first edition of Brújula in 1940, a Spanish newspaper published by my grandfather and four of his close compatriots for the sole purpose of disseminating the letter. Since this discovery I have been driven to focus on Puerto Rico’s colonial history through the legacy of my grandfather, born on the island four years after the US takeover. I began to closely examine what precipitated his decision to leave Puerto Rico and re-contextualize his experience with the present-day displacement of Puerto Ricans from the island.

Seeds of Colonialism

In 2016, I was awarded a Creative Workforce Fellowship made possible by the generous support of Cuyahoga County residents in Ohio through a public grant from Cuyahoga Arts & Culture. I decided to incorporate the research I was doing for an independent film into a body of silkscreen prints called Seeds of Colonialism and exhibit the work within the Puerto Rican community surrounding the Clark/Fulton neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio.

At the time, I had been living in Cleveland 12 years and was learning to appreciate a much smaller, more affordable city than New York, one with well-established cultural institutions and a diverse community. I committed to commuting to and from Kent State University so I could have the summers to live and work in Cleveland.

I felt like an outsider when I first approached different organizations, unable to break through the skepticism of not being from Cleveland and having no command of the Spanish language. With the support of the Fellowship, I would eventually develop a strong relationship with the Executive Director of the Hispanic Alliance in Cleveland, who was also of Puerto Rican descent. We sat down on multiple occasions sharing our family’s history on the island, in New York and for him in Chicago, and expressing concerns for the current challenges faced by Puerto Ricans and the Puerto Rican diaspora.

It was vitally important for the exhibition to be presented in the heart of the Hispanic community. As I was reaching out to different organizations in search of a space, a friend suggested the Studio House of Cleveland artist Elizabeth Emery—located in Cleveland’s Clark/Fulton neighborhood not far from the headquarters of the Hispanic Alliance. Elizabeth had wanted to have occasional exhibitions on the ground floor of her Victorian workspace so we were excited to combine our resources and turn the space into a gallery. We painted the walls and the trim of the gallery, and hung light fixtures for the inaugural exhibition of what was christened Some Time Gallery. Because of the gallery’s location, the Hispanic Alliance became an indispensable partner in making Seeds of Colonialism known to the Puerto Rican community.

Seeds of Colonialism was designed to directly engage with the Puerto Rican community and bring awareness to the greater Cleveland community of the origins of Puerto Rico’s relationship with the US. The silkscreen prints created for the project consisted of a series of six statements made by US government officials following the takeover of Puerto Rico in 1898. Visitors to the gallery were invited to anonymously comment on these statements at the opening reception on January 6, 2017 and throughout the month-long exhibition to be presented to the public at the exhibition’s closing.

As I was researching the events surrounding the US takeover, I became acutely aware of the actions of President William McKinley, born in Niles, Ohio in 1843. Unearthing President McKinley’s unbridled authority over Puerto Rico in 1898, and reading the proclamations of those from Ohio in the Senate and House of Representatives at the time, was a revelation. Moreover, shedding light on this history was not without irony. How could these politicians from a 19th century provincial Midwestern state understand and be given the authority to determine the future of the Puerto Rican people? It was suddenly an odd feeling living in, a swing state that had just voted in support of MAGA, and a stark reminder that I was no longer in New York.

Immediately after the takeover, McKinley established tariffs on Puerto Rican goods, such as coffee and sugar, to obtain the funds needed to administer a military government. Because of these tariffs and taxes placed on US goods by Cuban and Spanish markets in retaliation, Puerto Rican farmers were unable to compete in the global market. This eventually led to the complete devastation of Puerto Rican agriculture. Farmers unable to sell their crops found themselves on the verge of bankruptcy. At the same time Puerto Ricans were dealing with a substantial increase in the cost of living and were forced to pay for necessities with currency that was halved in value within weeks of McKinley’s decision to impose tariffs.1

The imposition of tariffs by McKinley on August 19, 1898 came less than six weeks after General Nelson Miles, Commander of the American Forces invaded Puerto Rico and made the following declaration:

American Invasion*

“We have not come to make war upon the people of a country that for centuries has been oppressed, but, on the contrary, to bring you protection, not only to yourselves but to your property, to promote your prosperity, and to bestow upon you the immunities and blessings of the liberal institutions of our Government. It is not our purpose to interfere with any existing law and customs that are wholesome and beneficial to your people as long as they conform to the rules of military administration of order and justice.”

–General Nelson Miles, Commander of American Forces, July 28, 1898

This declaration, however, did not prevent General Miles from suggesting to President McKinley in January of 1899 to make the US dollar the only legal currency in Puerto Rico, and to set the exchange rate at sixty cents to the Puerto Rican peso. This was the final straw that brought Puerto Rico to the brink of financial ruin and opened the door for corporate Americans in search of “opportunities in the colonies.”1

Another key player during this critical time for Puerto Rico was Senator Joseph Foraker, who was born near Rainsboro, Ohio in 1846 and served as Governor of Ohio. During his tenure as Senator from 1897 to 1909, he was instrumental in establishing the Foraker Act, which gave Puerto Ricans only partial control of their government and US-appointed government officials the final say in legislating the Puerto Rican government.

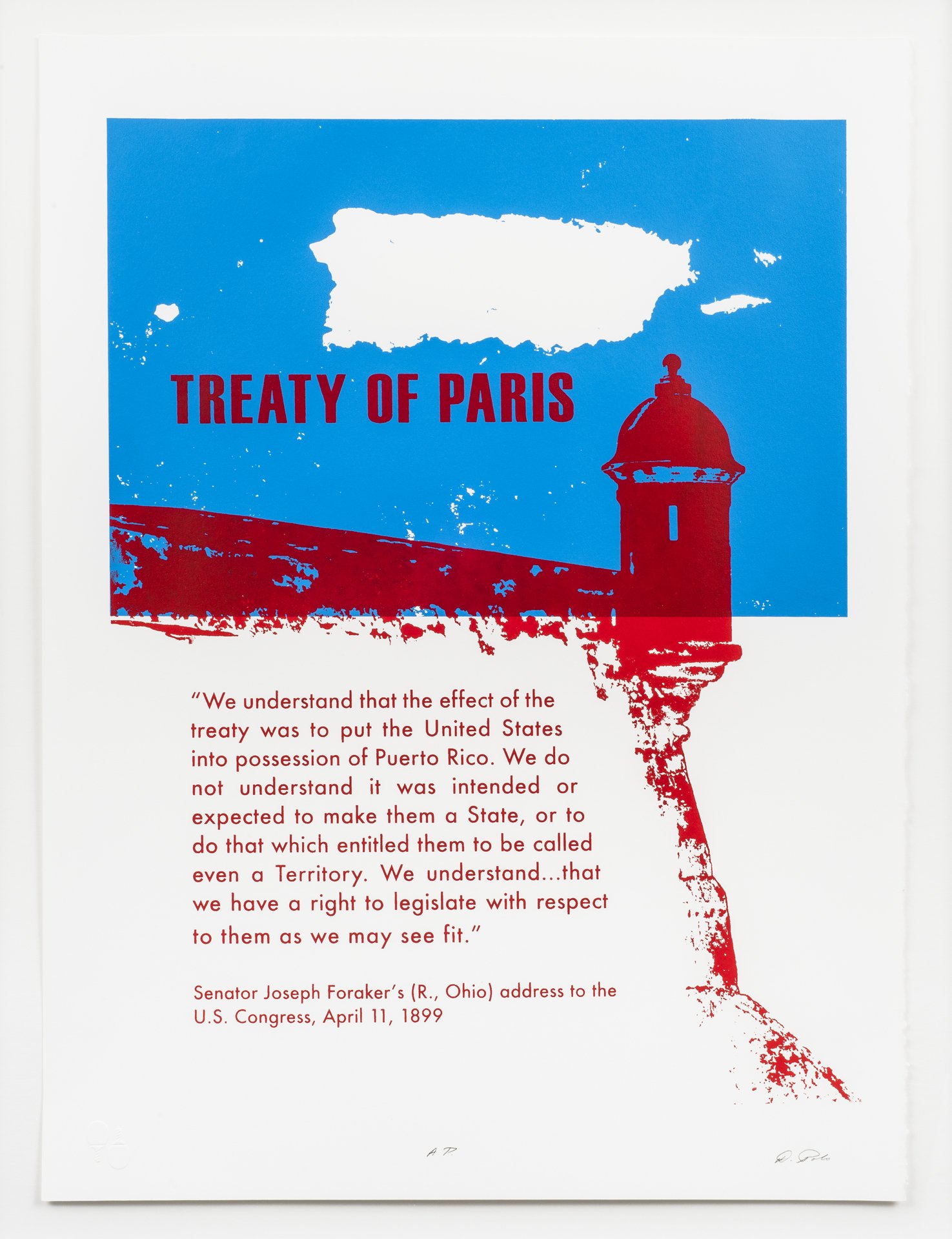

When Foraker addressed the US Congress, on April 11, 1899, he spoke about the Treaty of Paris, which was jointly signed by Spain and the US to end the Spanish-American War:

Treaty of Paris*

“We understand that the effect of the treaty was to put the United States into possession of Puerto Rico. We do not understand it was intended or expected to make them a State, or to do that which entitled them to be called even a Territory. We understand…that we have a right to legislate with respect to them as we may see fit.”

–Senator Joseph Foraker’s (R., Ohio) address to the U.S. Congress, April 11, 1899

When the simultaneous acquisition of the Philippines was not going as planned for the US government, US House of Representatives Jacob H. Bromwell, born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1848, addressed the House on March 21, 1900, and stated the following:

Legislation*

“…in order to show our assertion of authority we must make an example of Puerto Rico; and that we are anxious to have a test case made before the Supreme Court to find out just what authority we have in legislating on our new possessions…We propose, in this way, to establish a precedent for the Filipinos, the unruly and disobedient, by disciplining and punishing Puerto Rico, the well-behaved and well-disposed.”

–Representative Jacob H. Bromwell, (R, Ohio), address to House of Representatives, March 21, 1900

These actions and statements by President McKinley and Ohio government officials had a devastating impact on the Puerto Rican people and would set the tone for policies instituted by the US administration throughout 124 years of US colonialism. It was these debilitating policies that eventually caused my grandfather to leave the island with his family in 1927.

The exhibition Seeds of Colonialism opened on a cold January night in 2017 to an exceptional group of gallery goers. Among the visitors were many of my Kent State School of Art colleagues and students, and other fellow artists from the Northeast Ohio art community. While grateful for their attendance, it was especially exciting and exhilarating to experience the large turnout by the Hispanic community. Juan Molina Crespo, Executive Director of the Hispanic Alliance, pointed out to me that a gallery exhibition had not been shown in the Clark/Fulton neighborhood in decades. Many from the community were tentative when they first entered the gallery, but once they became engaged with the work and met up with friends, it became a warm atmosphere. As the evening progressed and conversation ensued I also sensed moments of indignation as the gravity of these statements took hold.

Military Government*

“If universal or manhood suffrage be given to the Puerto Ricans, bad results are almost certain to follow. The vast majority of the people are no more fit to take part in self-government than are our reservation Indians, from whom the suffrage is withheld unless they pay taxes. They certainly are far inferior in the social, intellectual, and industrial scale to the Chinese, who for very good reasons are forbidden to land on our shores.”

–Brigadier General George W. Davis, Military Governor of Puerto Rico, May 9, 1898 to May 1, 1900.

It is not surprising that General Nelson Miles, Commander of the American Forces that invaded Puerto Rico, also fought in the American Indian Wars in campaigns against the tribes of the Great Plains. In 1890 his efforts to subdue the Sioux on the Lakota reservations lead to Sitting Bull’s death and the massacre of about 300 Sioux Indians. He believed that the US should have authority over the Indians, with the Lakota under military control. This sentiment clearly exists in Brigadier General George W. Davis’s statement comparing the unfitness of the American Indian to the people of Puerto Rico.

Americanization*

“If the schools are made American and the teachers and pupils are inspired with the American spirit…the island will become in its sympathies, views and attitude toward life and toward government essentially American. The great mass of Puerto Ricans are as yet passive and plastic…Their ideals are in our hands to create and mold. We shall be responsible for the work when it is done...”

–Victor S. Clark, President of the Board of Education in Puerto Rico, 1899

Freedom of Speech*

“Publications of articles criticizing those in authority and reflecting upon the government or its officers will not be allowed.”

–Major General Guy Vernon Henry, Military Governor of Puerto Rico, December 1898

After reading the spirited comments left by gallery goers and building strong relationships within the Puerto Rican community, I felt fulfilled and aware that Clevelanders, a diverse community much like New Yorkers, renounced the harsh dominance of imperialism and empathized with the plight of Puerto Ricans. The exhibition was everything I envisioned it would be. It generated a wealth of research that has become the engine for a film.

Brújula

The independent film, Brújula, is intended to inspire conversation surrounding the tragic disconnect from one’s homeland caused by assimilation into American culture, and the adverse effect displacement continues to have on Puerto Ricans forced to leave the island for self-preservation. It will shed light on antiquated policies that have benefited US corporations and hedge funds and obstructed the Puerto Rican people from becoming a sovereign nation. It will present Ruperto’s voice and those of his compatriots by sharing the words contained in “Open Letter to a Libelist.” It truly was a gift to discover this letter and there is no question that my grandfather believed in independence for the Puerto Rican people. More importantly, the film will provide ways to advocate for the decolonization of Puerto Rico and direct Puerto Ricans living on the island to comprehensive initiatives for a binding path toward self-determination.

I Put A Spell On You, 05:38 Single Channel Video, 2020

In I Put a Spell on You, the song’s lyrics introduce competing undertones between dominance and resistance while the music serves as the structure to rhythmically organize sequences of images. This video short contains footage of Puerto Rico: from family films, the National Archives in Washington DC, and before and after hurricanes Irma and Maria.

Excerpts from “Open Letter to a Libelist”

The Puerto Rican is not a man who emigrates. This is to say, he is of the type who abandons his native shores only when imponderable events deny him access to daily sustenance. Moreover, already emigrated, he continues to think of his emigration as a transitory thing and continues to dream of the longed-for return. For that reason, he does not renounce his rural personality but keeps the defining contours of his culture alive...

If the American people and their government want to stop Puerto Rican emigration to this country, they have to begin with recognizing the right of the Puerto Rican people to control their own destiny…

That is not the only thing the United States has to do…

The United States also has to legally repair all the wrongs it has occasioned upon Puerto Rico over the past 42 years of mismanagement.

“Open Letter to a Libelist” was published in the Bronx periodical, Brújula in March of 1940 by Lorenzo Piñero Rivera, Ruperto Udenburgh, Gerardo Peña, Carlos Carcel and Ramón Rodríguez. It was written in response to a defamatory article, published in Scribner’s Commentator in 1940, called “Welcome Paupers and Crime: Porto Rico’s shocking gift to the United States” by Charles E Hewitt, Jr. The article proposed ways to curtail Puerto Rican emigration to the mainland and blamed Puerto Ricans for the emigration resulting from American colonialism.

*English (left) and Spanish (right) versions of “Open Letter to a Libelist” are available below by scrolling down.

Footnotes

1. Ronald Feldman, The Disenchanted Island: Puerto Rico and the United States in the Twentieth Century, (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1996), pp. 1-22.

2. Peter R. DeMontravel, A Hero to His Fighting Men, (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998), p. 206.

Darice Polo is the director of the independent film Brújula. A full-length film in post-production, it recounts the birth of US colonialism in Puerto Rico and the subsequent emigration of her Puerto Rican ancestors to New York in 1927.

Polo is the recipient of a grant from the Puffin Foundation, and Cuyahoga Arts and Culture. She was also a participant in an International residency at the SFAI in New Mexico. Video shorts related to Brújula were recently screened at A.I.R. Gallery in New York, and in the 2018 Creative Time Summit at the Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, Poland.