Soulcrafting Interiors: Kansas City’s Art Systems and the Knowledges We Engineer

Kansas City (KC)—self-declared Soccer Capital of America and indigenous homelands to the Missouria, Oto, Kansa, Osage, Shawnee, and Delaware—is a waning and waxing contemporary art system. During a spring 2023 pilot curatorial residency with KC artist-run-project space Curiouser & Curiouser (CC), I was introduced to KC’s art world and was in conversation with multi-hyphenated art workers who are seeding projects in this Mississippi River Basin (MRB) city. As a Chicago-based art worker consciously seeking my contemporaries in the heartland region and beyond, the curiosities are: What projects are creating generous eco-systems that expand power and forefront the region’s potentials? What are the wants and needs of the region and who is facilitating them? How do these activities fit in the ether of global art and within the soul of contemporary American Art?

This interview talks with my hosts of the residency: Cesar Lopez, Samantha Haan and Aquetzali “Kiki” Sierna. We touch on Cesar Lopez’s practice, Kansas City’s art context, and La Onda, an exhibition project centering Latinx KC artists.

Born in Coatepeque, Guatemala and graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute (KCAI), Cesar Lopez’s (b. 1991) artistic work speaks on interiorities, technologies, and cartography. They co-direct CC with Samantha Haan and La Onda with Kiki Serna. Lopez has their first museum solo show at the Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art planned for Fall 2024. In full transparency, this piece initially was solely about Cesar. I proposed to them a 1:1 interview, however, in tradition with their movement strategies to make conversations wider, this piece zoomed out to include KC. Before we get into KC and La Onda, I asked Cesar about their practice and more about Soulcrafting.

—

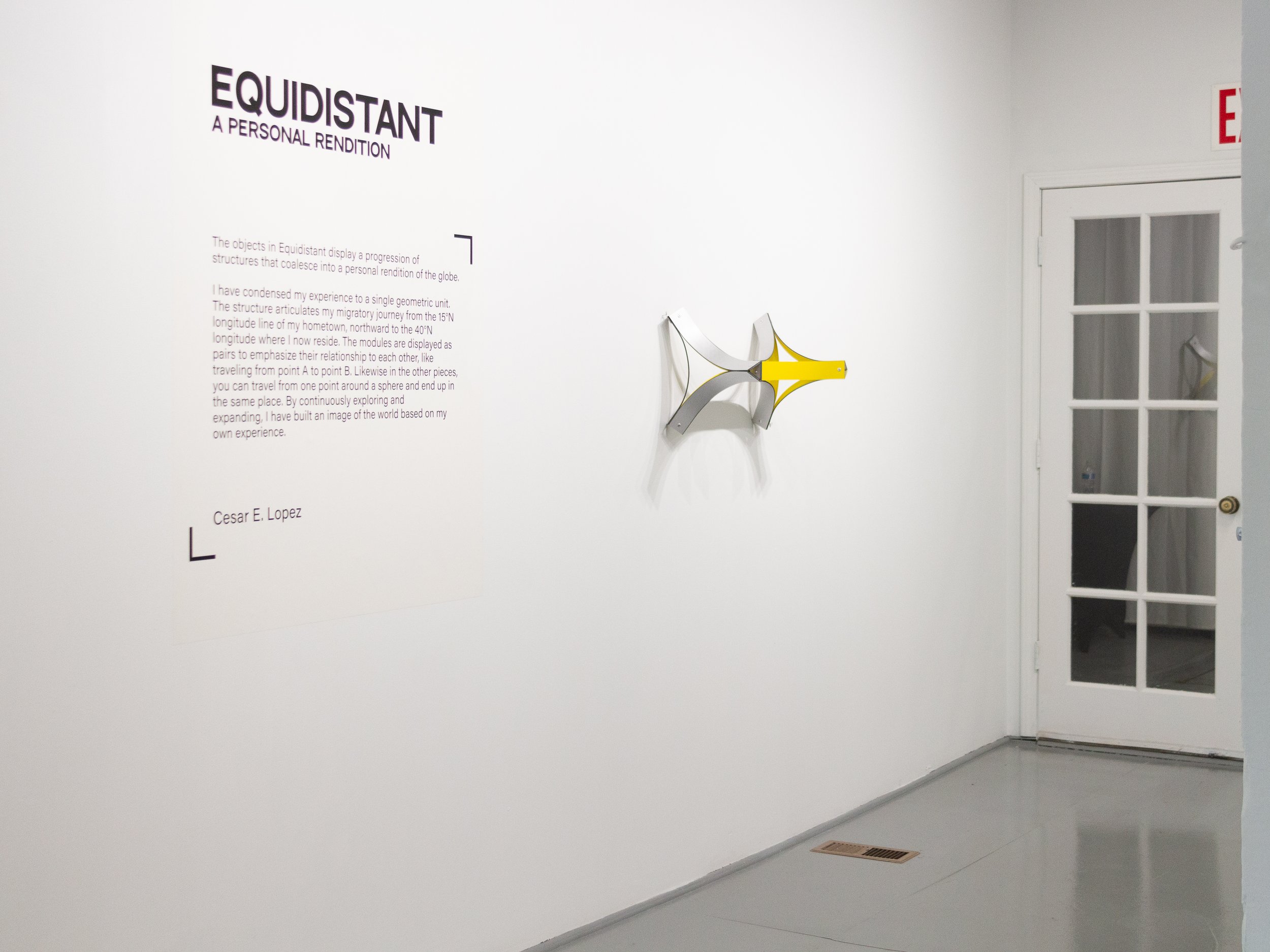

Guevara: What prompted my visit to KC was to see your solo show Equidistant at Gallery Bogart. I also was looking for a short-term curatorial residency in the Midwest, however, there isn’t any in the region. To feed two quetzales with one fruit, we drafted the pilot residency as a project for me to see the show and also engage with KC. The sculpture works at Gallery Bogart are interpretations of globes that use two coordinate points from your personal biography as framing units. Notions of map-making, military technologies, and glocal empathy came up during our conversations about the work. Can you expound on this series and your studio practice?

Lopez: The studio practice is based on the expanded field of painting. My research is based on destruction, construction, iteration, and investigation of ideas around geography. I have spent time studying these ideas. Assembling and rearranging them for myself. Including maps, flags, and lately, globes.

As you mentioned John, the latest body of work is centered around the making of large sphere-like sculptures and the components that contribute to it. The sculpture work is built in painted aluminum and fastened together with rivets. The hardware locks the structure with the appropriate amount of tension, which helps it retain its form. In Equidistant you will also see iterations and parts of the greater whole, for example [in the works named] structural couplings and structural ring. These pieces are variations on the single, hollow, triangular-like parts that make the entire body of work.

Guevara: This text’s title and your work loosely reference Matthew B.Crawford’s essay “Shop Class as Soulcraft: The Case for the Manual Trades.” Crawford’s essay positions manual labor and craft skills as ways one can find personal fulfillment and shared consciousness through the tactile and cognitive comprehension of a technology's properties, activities, or behaviors. Technology meaning objects, materials, apparatuses, devices, machines, systems, etc. The text defines craft workers as knowledge workers because craft conjures past knowledges that went into engineering, producing, and teaching those given technologies. Maybe said another way; craft work, because of touch and memory, is a conduit for one’s soul to feel interconnected with a specific temporality and satisfies one's position in that constellation.

Lopez: That's right! I have come to understand this soulcraft in the studio as a dual practice. At times the more I work in the studio, the more I work on myself. I would like to believe that as the quality of my work increases, so do I. The two are tied and grow towards greater quality and also fall away from quality, together.

Guevara: What do you take away from the essay?

Lopez: My biggest takeaway is the modes of looking and understanding. The classical way; which is to understand the technical part of the studio work, where the fasteners meet and how they hold materials together. Likewise, the technical document that goes to the manufacturer when the metal is cut. Whereas in a romantic way, as mentioned in the book; it is the poetry and lyricism formed that can take on its many values. We are tasked (as artists) with connecting these ways of thinking to produce something of quality.

Guevara: In your studio right now you're prototyping the object’s potential as a prosthesis or surrogate. Through multiplying the unit’s form, blushing colors, and stage photography, the assemblage of these aluminum bands hope to function as a stand-in for emotions, sensations or narratives. The reach is that the object, or the image of the object, is not just a projection of one’s logic or meaning, but it is prosthesis or surrogate of those feelings.

Lopez: Yes, right now the work is a surrogate for the landscape, much like a bridge over a river. The work is a constructed continuation of land. Due to the modularity of the work, it has so much potential for forms.

Guevara: Also another facet of the work, in your words, is that they point to Retazos, a quilt weaving of left-over fabrics.

Lopez: Yes, Retazos are fragments of a greater whole in terms of textiles. My mother was a seamstress and so much of that way of thinking is how I approach problem solving.

Guevara: What is the most interesting part of playing with the object right now?

Lopez: The potential for scale! Because the work is made of many parts, it can be reassembled into larger forms. There will be an example of this later this year at the upcoming exhibition at the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

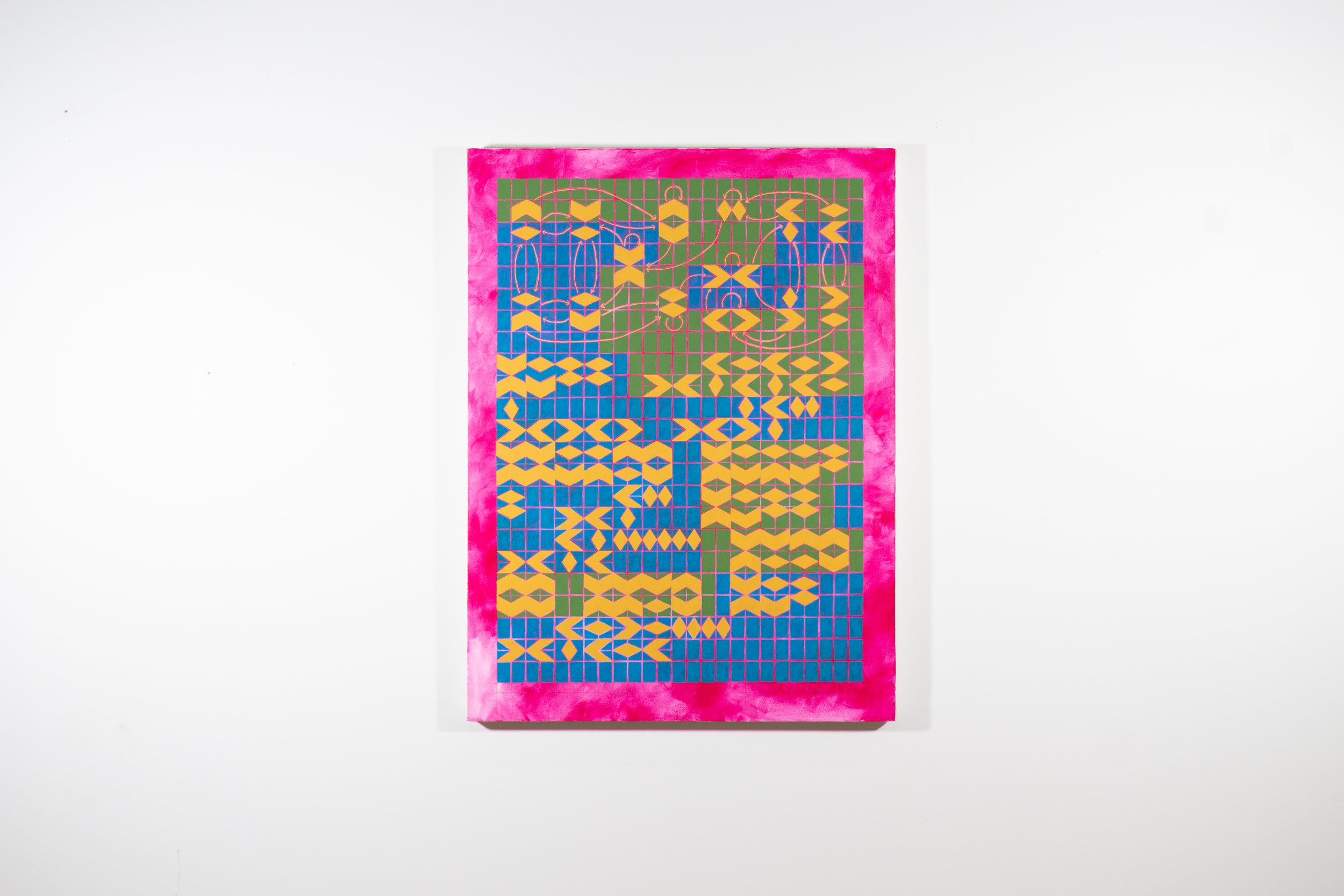

My main tour guide in the residency was Samantha Haan (b. 1997). Sam came to KC from Texas to attend KCAI where they met Cesar and are now teaching at the school. They use signs and iconography in their painting practice to speak on translation and language. As the curator of CC, they translated KC's art landscape to me. I turn to Sam to answer questions about KC’s art context and CC’s genesis.

—

Guevara: Independent art spaces run deep in Midwest cities because of lack of formal channels to get professional development or even places to show one’s work. CC feels like a sister project to my project in Chicago, as we are unapologetically pirating resources for art workers and building activities in hopes to fertilize an abundance and self-starter culture. Furthermore we are responding to specific social and cultural nuances of KC and Chicago in which inherently, all the problematic racism and colonial functions come with.

Can you take it back and describe the KC art ecosystem that you adopted and CC’s genesis?

Haan: The KC art ecosystem is supported majorly by artist-run spaces. The history of DIY spaces in KC is championed by the community creating a very positive local environment. However, these spaces fluctuate, causing the ecosystem to grow and shrink periodically. During a period of shrinking, Cesar and I started Curiouser in an office space. We focused on showing local emerging artists to fill where the opportunities were missing.

Guevara: I talked with a handful of artists during the residency, including Andrew Mcilvaine, Ruben Castillo, Leon Jones, Bernadette Negrete, Noelle Choy and Rodrigo Carazas to name a few, and a sentiment is that the city can benefit from more formal academic criticality or criticism, as a city with no MFA program. I caution that wish because coming from Chicago, which has a handful of MFA programs, performing criticality is a thing and MFA capitalism is a thing.

Similar to Chicago, there is a revolving door of artists coming and going in KC. What are some opportunities of growth you see in KC for artists?

Haan: There is a strong ecosystem for young emerging artists and support for established artists. There is an opportunity for growth to develop paths for those emerging artists to become “mid-career.” This could be mediated by galleries that support new artists and curators who promote local artists and bring them into a national context. This would allow emerging artists to gain traction, allowing them to stay in the ecosystem and continue to develop instead of being in its current cycle of growth and decline.

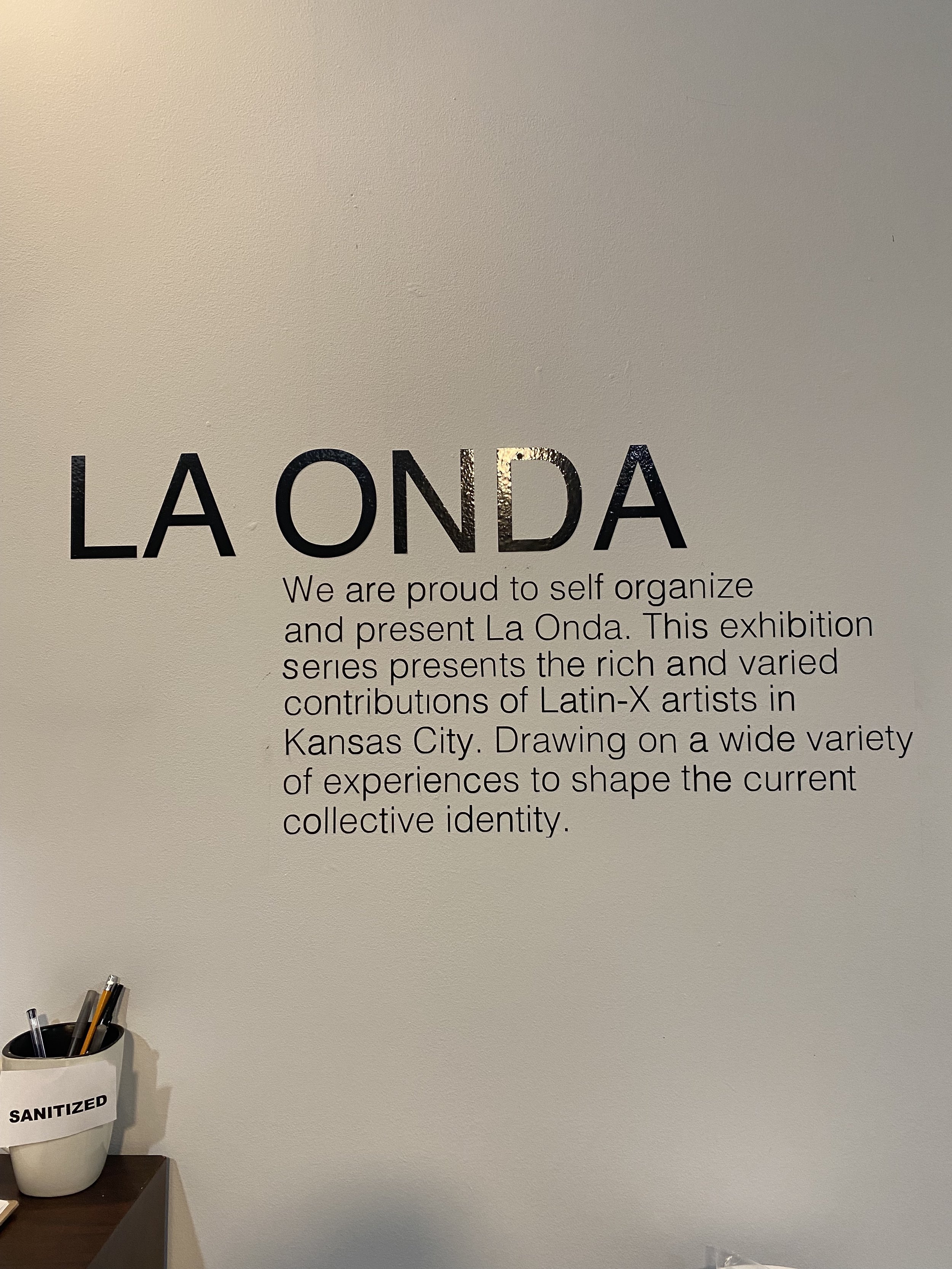

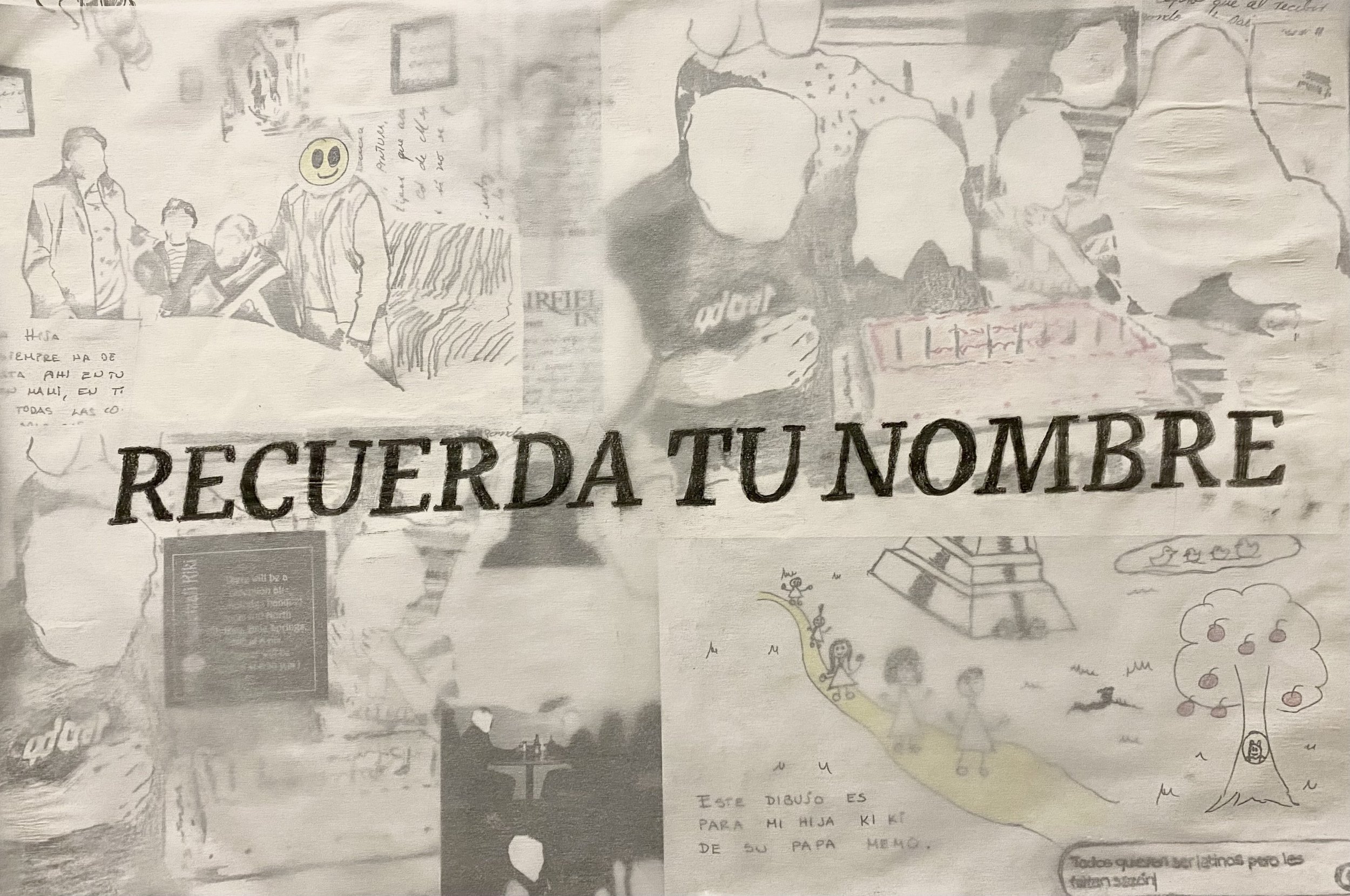

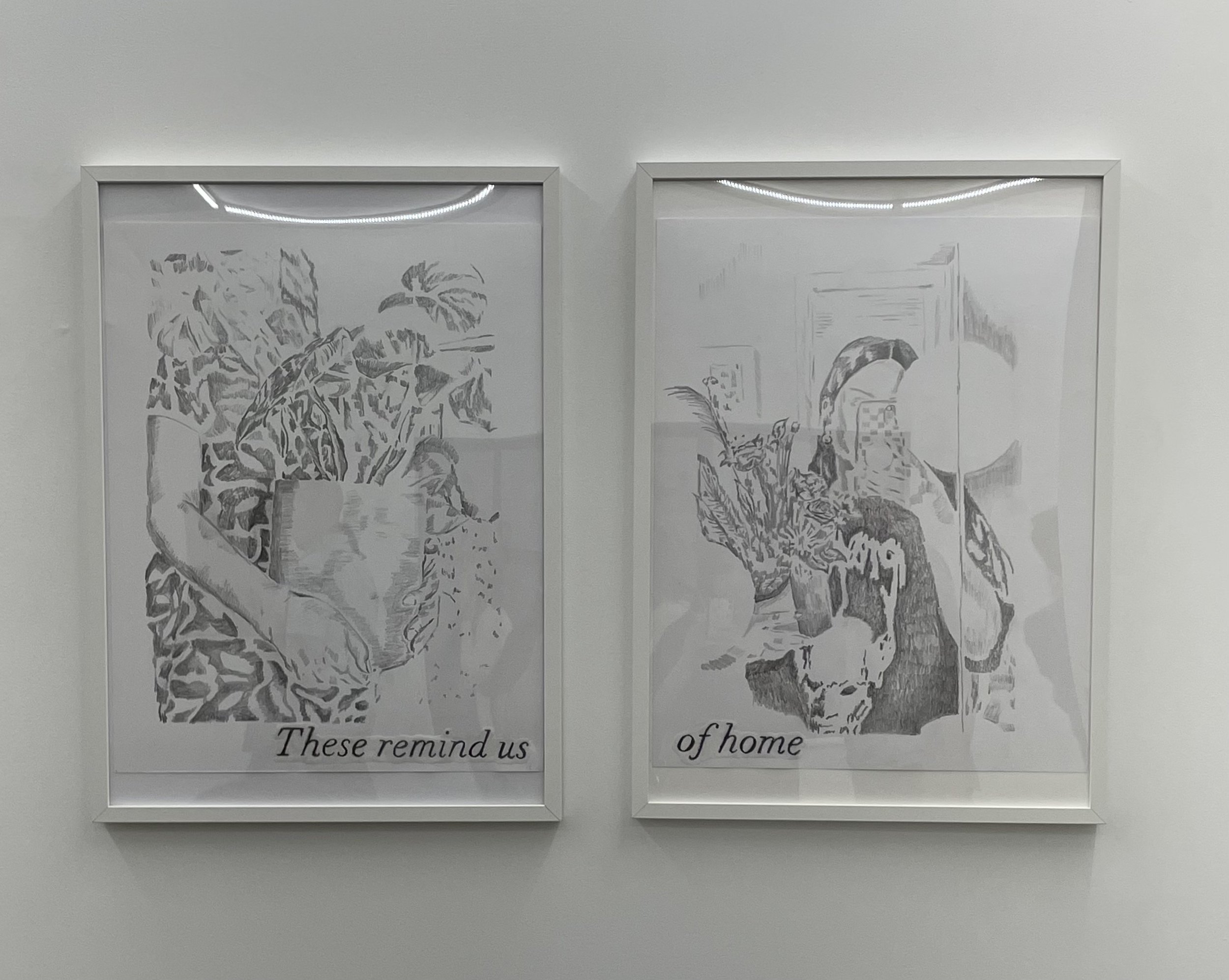

To get specific on the Latinx/a/e/o art discourse in KC, I ask Kiki Serna (b.1994) about La Onda, a KC Latinx centered exhibition project that semi-lives in a repurposed shipping container. La Onda projects have taken place in Mexico City and Chicago. Serna was born in Mexico City and raised in KC. Also a KCAI graduate, they work in collage, painting, and text to speak on memory, catharsis, and migration. Serna co-runs La Onda with Cesar and is Cultural Arts Coordinator at one of the longest operating art and cultural organizations in KC, The Mattie Rhodes Center.

—

Guevara: There are a handful of projects centering Latinx KC artists right now in KC. In trend with nationwide institution's responding with DEI initiatives because of 2020 events, The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art is organizing a Latinx exhibition later this year with 22 artists, in which Cesar and yourself are participating in. Gallery Bogart, as a commercial gallery, is vocally promoting Latin American artists in their program. Also, there was the Inspired by Maya exhibition this year curated by artist Chico Serra in which 24 Indigenous and Latinx artists responded to Maya The Exhibition: The Great Jaguar Rises at Union Station. With this momentum of pronouncing a Latinx KC artist, tell us about the genesis of La Onda and its contribution to KC’s Latinx art dynamic.

Serna: La Onda was born during the pandemic, Cesar and I had been in talks during this time in regards to what moves to make when the city was closed. We wanted to continue to create and exhibit while continuing that energy after COVID.

We talked to other soon-to-be La Onda artists and most of us landed on the idea that we wanted the same thing—to continue to be productive during the pandemic. Post-pandemic, La Onda has shown locally but has also left this city.

An important message behind La Onda in regards to its context in the Midwest, primarily Missouri/Kansas, is the importance of showing up and building momentum. La Onda has been an avenue that has made room for itself, while also opening up other opportunities not just here but also outside of KC.

The energy that’s shared with groups like La Onda connects other collaborators to also be part of that symbiosis. I think La Onda has been a great tool for those shared experiences.

Guevara: Coincidentally or by fate, when I was in KC, the Smithsonian was in town surveying KC’s Latinx art and culture actors about the forthcoming National Museum of the American Latino and its traveling program. In the survey session event, I learned about the railroad system being a pull factor for Mexican-American and Chicano/a workers to reside in KC’s Westside neighborhood. I also learned about Jenny Mendez, current Cultural Art Director at Mattie Rhodes, as being a prominent initiator to many projects in the city. A fun note is that Mrs. Mendez and yourself were featured in the PBS special We Are Latino, a documentary on KC’s Latino community. Can you give us context of the Latinx/o/a/e diaspora in KC and the work you do at Mattie Rhodes that serves the area?

Serna: Kansas City brings a lot of Latinx/o/a/e families, narratives, and experiences. In comparison to bigger cities, KC is small. This lends itself to the ability to make moves while connecting and feeling supported by your peers. Most art spaces are already intertwined to one another or in the process of collaborating. Therefore, when it comes to doing the work there is usually good support.

In regards to my work at Mattie Rhodes there’s only a handful of Latino non-profit organizations in Kansas City. Because of this, the message has always been to collaborate and become community partners because at the end of the day, we’re serving the same communities. Working collaboratively and working towards similar goals is more doable to do when we’re all centrally located and already connected.

There is a part in Crawford’s essay about diagnosing a discontinued motorcycle model needing repairs. They state that it will probably be impossible to fix outdated machines in isolation without knowledge workers having access to a collective historical memory and a country wide network of reciprocal favors and lores.

It would feel desolate to be working in the MRB without the interconnected art rivers and value systems Cesar, Sam, Kiki, and I are presently irrigating in the region. Thinking about knowledges and functions of the Midwest in American Art, claiming that present collective work and exporting that knowledge to the edges of the country and globally is seminal for power and potential. And to make it clear, there is no intention in repairing outdated racist and colonial art structures in this basin. The proclivity is to engineer culture, technologies, and systems for present and future knowledge workers soulcrafting in the American interior.

John H. Guevara is a curator and art worker raised and based in Chicago. They were recognized as one of Chicago’s top art workers and organizers in Chicago’s Newcity Magazine’s Art Top 50 2022. They’ve done curatorial residencies at Curiouser and Curiouser (Kansas City), No Lugar Arte Contemporaneo (Quito, Ecuador), and Chicago Artist Coalition (Chicago). They founded and currently direct Chuquimarca. Chuquimarca is an art library project that programs a seasonal research group program called Tanda, and a summer art writing program, with online art publication Sixty Inches From Center, called Muña. They have been invited to program and advise with art organizations such as The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Depaul Art Museum, Hyde Park Art Center, Mana Contemporary, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.