Victor Hernández Cruz’s Tropicalizing, Circular Migration

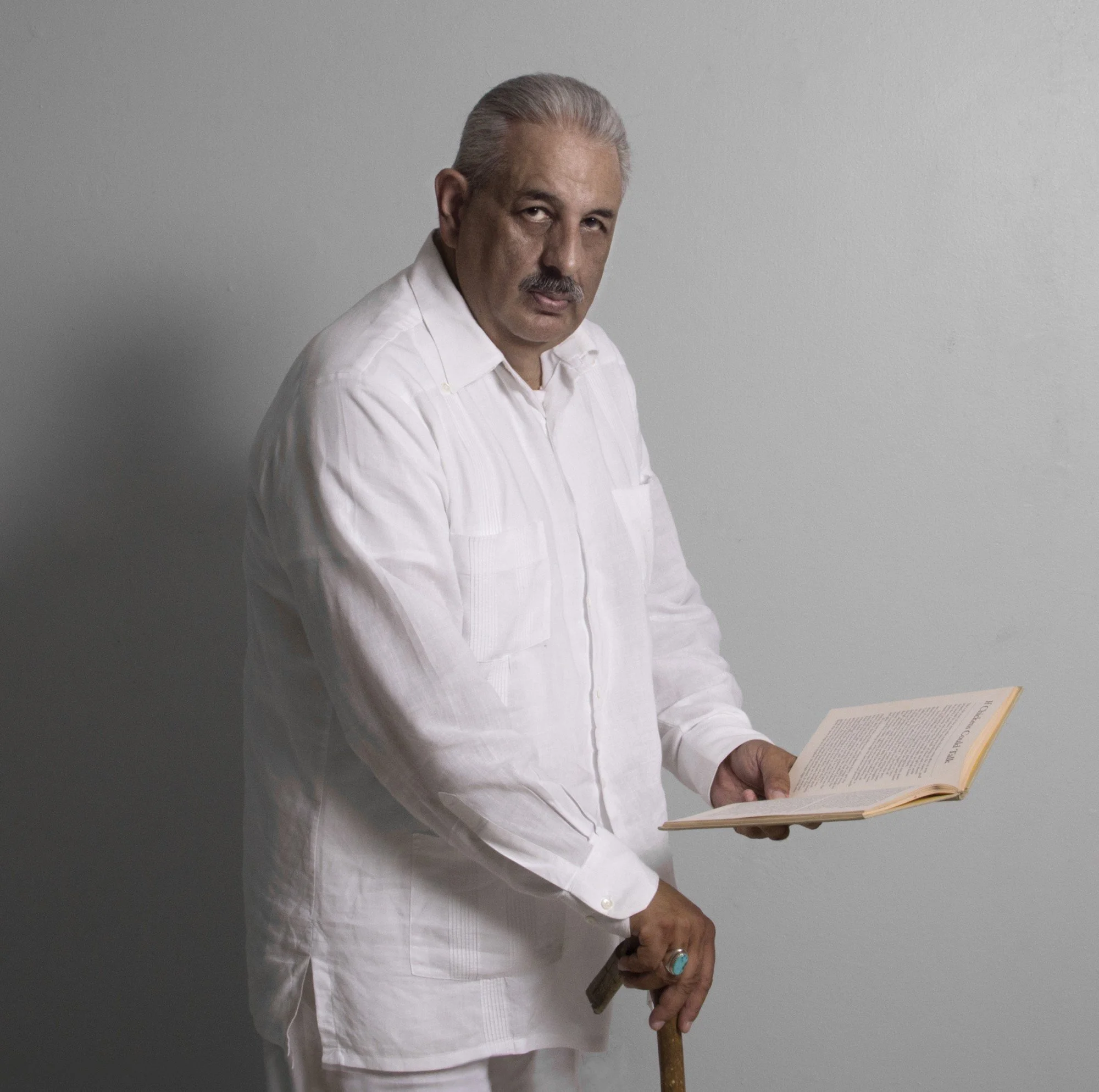

Hanging out with Victor Hernández Cruz in Adela’s on Avenue C is a little like visiting a temple or shrine of Nuyorico. He holds court with a kind of deadpanning prophesy, like an oracle descended from Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico by way of Loisaida. His eyes widen as the ensalada de aguacate and plátanos maduros arrived, absorbed in the aromas of home. While his conversation is casual, intimate in the way of New York elders like stickball players or salsa sidemen, sometimes it’s as if he is working out his writing as he’s speaking. Even his emails, which arrive mysteriously at 3am from his home in Morocco, follow a prosodic rhythm, each line containing 5-7 syllables, with spaces for breathing.

“You have to be influenced/by the writing of the past,” he said softly, when I asked him about what it was like to “invent” bilingual Nuyorican poetry. “To write, you have to read/To paint, you have to see paintings. To do music you have to/listen to music.” Then came the Hernández Cruz caesura, the pause for reflection. “I enjoyed myself/reading Jane Austen/Pride and Prejudice/Sense and Sensibility/you know, those two sisters/talking about the man/the other sister/wants to marry/It’s like gossip/as literature,” he said, invoking an unexpected turn to conventional literary canon as one of his sources.

Maybe it was his way of explaining tropicalization, a literary method he coined with his 1976 book of the same name. Appropriating Austen as an inspiration, as he later did Mark Twain, J.D. Salinger, James Joyce, William Faulkner, even Virginia Woolf’s A Room of Her Own, was all part of the balancing act of writing Nuyorican by employing slippery signifiers gleaned from nights at New York salsa dancehalls like Casino 14, the Hipocampo, the Bronx Music Palace, and of course, the Corso. Agile and unyielding, like the dancers he takes notes on, Hernández Cruz tropes lo tropical as a coping mechanism, using the clave rhythm as a contradiscurso, rejecting Anglo hegemonies. He has spent a career tropicalizing the urban landscape with mango, guayaba, palmas and pachanga, using the language of capicú and bugalú.

Victor is always very present wherever his physical location is, despite, or perhaps owing to his nomadic nature. The theme of exile is constantly a factor in his poetic being, whether practiced orally or via the written word. Born in Aguas Buenas, exiled to Loisaida; just as the idea of Nuyorican was taking off, he is exiled again to San Francisco, where he bonded with surrealist photographer Adál Maldonado, then back to New York, by the turn of the millennium back to Aguas Buenas, and now, Morocco, reconnecting with an imagined Andalusian past. In my living room, his works line the bookshelf: early classics like Snaps, Mainland, the aforementioned Tropicalization—which I bought in City Lights in San Francisco as a 19-year-old—mid-period masterpieces like Rhythm, Content & Flavor, Red Beans; and his Maghreb-tinged recent work like In the Shadow of Al-Andalus and Beneath the Spanish.

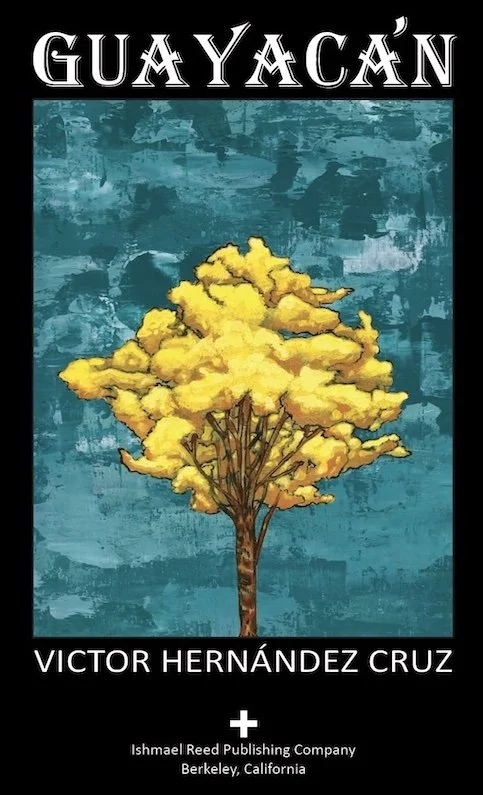

Now we are at La Sala de Pepe and Victor is signing a copy of his latest, Guayacán, which features poems dedicated to Bobby Sanabria, Chocolate Armenteros, and Pablo Casals. For this release, he had reunited with Ishmael Reed, who had published Tropicalization on Reed Canon Books, reminding me of Steve Canon and Victor’s long friendship with Umbra Poets like David Henderson, the influence of African-American letters on his work. He had just performed at Bob Holman’s Bowery Poetry Club with Nancy Mercado, and scholar Frances Aparicio—who had done so much to create an academic foundation for the tropicalization idea—had come to see it all.

Victor was explaining the neighborhood he grew up in, cutting through linear time as if nothing had changed.

“The Dragons were right here on Sixth Street,” he murmured, remembering the street gang. “And I once a few times went around that block and hung out with them, just an observer. I was just hanging out with my friends that were interested in them. I used to go to the Strand Bookstore, which was at another location. And I also used to go to Jefferson Bookstore, which is right off 14th Street on Union Square area. And Jefferson Bookstore was owned by the Communist Party and they had all kind books. There I found Jesús Colón, A Puerto Rican in New York, I was very excited.”

He began to develop his own voice in his late teens, when he published his first chapbook, Papa Got His Gun, after distributing it by using a mimeograph machine. “We distributed it ourselves to the local Eighth Street Bookstore, which was a big bookstore at the time. We left 10 copies and they sold them out. They were like 75 cents each.”

As a young New York Puerto Rican in the ‘70s he rubbed elbows with many of the era’s principal protagonists—he met Young Lord Felipe Luciano through Felipe’s brother, introduced himself to Eddie Palmieri at a gig, and hung out with Miguel Algarín as he was just opening the first version of the Nuyorican Poets Café on Sixth Street. He met Diane Di Prima and went to Newark to visit Amiri Baraka. But while he was largely sympathetic to the political upheaval of the counterculture years, Victor knew early on he should concentrate on writing.

“I was separate from any activism. I never joined any organization,” said Hernández Cruz, without regret. “I did some housing organizing during that period, because there was a lot of rent strikes going on in New York City, and they had the gigantic mobilization that went downtown to City Hall. But finally, I felt I was better off being a poet and writer than being an activist.”

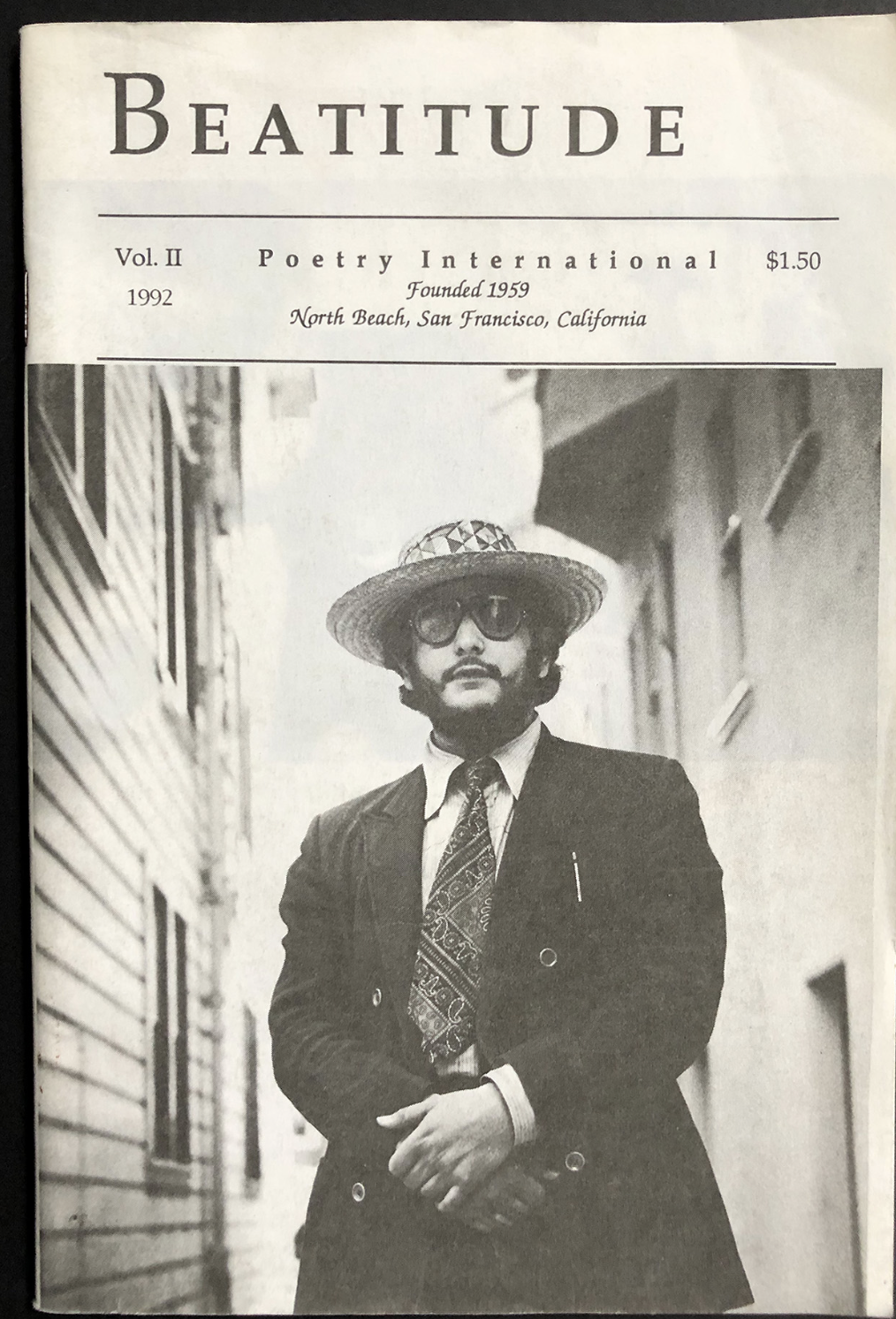

Soon Victor was offered a job teaching in San Francisco by Herbert Kohl, the founder of the Teachers and Writers Collaborative. He briefly intersected with beat poets: he met City Lights Book Store founder Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and when he came back to New York to visit, he stayed with Allen Ginsberg in his apartment on 12th Street when his family, who lived on 11th didn’t have enough room for him. The writer and public intellectual Robert Duncan introduced him to the little-known Puerto Rican enclave in San Francisco’s Mission District.

While in the Bay he met Adál Maldonado, whose passing in 2021 rocked the Puerto Rican arts community. His startling, innovative work, exemplified by his “Out of Focus Nuyoricans” series and his creation of El Puerto Rican Passport, collaborating with Pedro Pietri and New Rican Village founder Eddie Figueroa, was crucial in keeping the energy of the 1970s movement alive. “I met Adál first in California,” sighed Victor. “He was a student at the Art Institute of San Francisco. We became very close, and we hung out a lot. He took photographs of me and he wanted to me to write him the introduction to his first book.

“When he met Pedro Pietri, he got more political, where before he was more into his art form and surrealism,” Hernández Cruz continued. “He was a great artist and in terms of what he did with the camera, and actually printing the photographs, he did all the developing himself. He influenced me and I was an influence on him. There was something about the last time I saw him, he hugged me in this different way, and I realized something might be wrong with him.”

And then, another silence, like we had reached the final act of My Dinner With Andre, but instead, this film we’re in is about two Nuyoricans unstuck in time. On the table in front of us, the new book is open to page 100, which contains the poem “Leña de Guayacán.” I begin to read it silently… “Memory can voyage/Disappear history our toes/Dancing upon the ships/What wood cedar, oak, Spanish/Carabelas timber navals Arabic design/Back in the guáracas of time.”

Like the time, back in the ‘80s, when he ran into Miguel Piñero when he was on his last legs, living in a back room of the edgy Neither/Nor, a smoky bohemian den on 6th between C and D. The time Ray Barretto had Papy Román recite Victor’s “Drum Poem” on the obscure 1972 Head Sounds LP. The time in Fresno, when the Royal Chicano Air Force was flying under the radar. The time we dropped Adál off in the 100s on Central Park West, not far from where my grandmother lived in the 1950s, after a book event in the Village. The last time we saw him.

We could hear Pepe rustling around in the back room, and it was getting late in the afternoon. So, what’s it like to live in Morocco, I said—it just bubbled up out of me, seemingly out of context, but of course it was the context. “They have this great restaurant where you buy the fish. And they come back for you and you go sit down. They have bread,” he smiles, “and you can smell the fish. ¡Yo soy moro! Es la culpa de los españoles. My whole family's like that. My cousins are like that. I speak a few words in Arabic, and I can feel at home with them.”

Victor feels the vibe that Al-Andalus and Maghreb (North Africa) were like two wings of the same bird, the connection between Africa and Europe. His poetic presence is a practice, busy transcending time and tropicalizing spaces and finding home in unexpected places. Nomads keep nomading, and when he’s back in Loisaida, it’s just another point on the arc of life, his own personal circular migration.

It's a migration that gets him tantalizingly closer to the truth.

“In Islam you get more of the feeling that díos no es humano, it’s some…thing that we can’t perceive what it is,” he said soberly and without sentiment. “You can penetrate different systems of wisdom and spirituality, and you can approximate something that would be that, but you can never really get to it. My son goes to la mesquita cada día a las ocho. In a sense, I am a Muslim and I am a Christian. But I'm a non-practicing Christian and I'm a non-practicing Muslim. But something's taken care of us, especially through faith. But it is still all a mystery to me. It's still a mystery, you know?”

Ed Morales is an author and journalist who has written for The Nation, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, and CNN Opinions. He was staff writer at The Village Voice and columnist at Newsday. He is the author of Fantasy Island: Colonialism, Exploitation, and the Betrayal of Puerto Rico (Bold Type Books), Latinx: The New Force in Politics and Culture (Verso Books 2018). Morales is a lecturer at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race and a 2022-23 Mellon Fellow at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies.