A Family Affair: Justin Favela & Bertha Gutierrez Bring 'Family Fiesta' Back to Arkansas

“They will not know I have gone away to come back. For the ones I left behind. For the ones who cannot out.”

–Sandra Cisneros, “Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes”

When, at fourteen, I read this line at the end of The House on Mango Street, I saw what I hoped my life would be. Twenty-six years later, living 3,000 miles away from the city where I was born and raised, its meaning has evolved as Justin Favela and Bertha Gutierrez-Tejada—two of the three people I walked with almost every Wednesday from the quarantine fall of 2020 through the spring of 2022—remind me of the importance of collaborative creative practice.

It was in the offices of the Marjorie Barrick Museum where I met Favela, who, months later, introduced me to Bertha Gutierrez-Tejada. It’s important to note that before I formally start talking about the Family Fiesta performance that took place on May 13th at the Jones Center in Northwest Arkansas, I approached observing and participating in the final days of preparation as someone who had befriended the artists years before we transitioned into this working relationship. As Latinos living in Las Vegas with distinct social locations–Favela born and raised; Gutierrez-Tejada, a first-generation immigrant who arrived in Arkansas as a teenager and whose work, like mine, brought her to the Vegas valley in the mid-2010s. While our love for pop culture fueled our weekly quarantine walks across Vegas parks, the community we built with each other on those Wednesdays provides the lens around which I will approach this discussion.

Favela first organized Family Fiesta at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in October 2014. In an interview that took place after the Denver Museum of Art performance of 2017, Favela explained:

“In Family Fiesta, the event is taken out of its traditional context (a cookout in a backyard or a park) to unconventional locations, seeking to highlight people’s expectations of a fiesta—Latino party—and, at the same time, dismantling notions of location and institutional inclusion.”

As Latinos in our professions, we navigate others’ expectations of both our work ethic and capacity in ways that Gutierrez-Tejada and Favela’s preparation and relational navigation made clear.

On the way back to the Live in America residency house midweek, Favela explained to me that for this fiesta, he was both artist and facilitator in collaborating with Gutierrez-Tejada around the aforementioned vision of the show. On meeting Gutierrez-Tejada, I learned she first encountered Favela and his work during his Crystal Bridges’ residency. In other words, their collaboration brought full circle a friendship and creative practice that seeks to celebrate their communities. A painter and activist in her own right, this rendition of Family Fiesta centered around her family, who has made a home in Northwest Arkansas since leaving El Salvador. When I asked her where to go for walks after moving at the end of 2020, she was the one to suggest inviting Justin because it would give all of us time to get in our steps and build community together.

In the days leading up to the event, Favela, the Gutierrez-Tejada family, and friends met with Jones Center staff and Live in America residency staff to finalize details. Driving with Favela and his photographer and close friend, Mikayla Whitmore, as we bought supplies and worked at his studio, I considered what it meant to find so much Latine diversity there. Time in the car had me revisiting the humidity and wide open green landscapes that reminded me of Puerto Rico in contrast to Mexican-owned grocery stores stocked with Mexican, Central American, Puerto Rican, and even Dominican food stuffs that catered to this diversity.

With thunderstorms and sunny days alternating, on top of the allergies that were attacking those of us who had gotten accustomed to southern Nevada’s pollen, it wasn’t yet clear where to host the fiesta. In reviewing the park and green space, the diversity of natural resources became centerstage as Jones’ staff discussed integrating the significant tree if Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada decided to host it outside. Following the weather and thinking about foot traffic and visibility, however, Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada asked which rooms and open spaces could function as alternative sites. The storm the Friday before Saturday’s fiesta made the decision for them, which Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada’s decorations had considered.

While they had worked from breakfast at the restaurant next to the Live in America residency house through late nights, I participated as much as I could, given the delayed flights’ toll on my lower back. In the hours I spent on my own, when not sleeping, I began to take note of the emergent themes I had observed while following Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada throughout the week. During one dinner, I reflected on how much my five-plus-year friendship with Favela had changed my intellectual trajectory. As a professor at UNLV, I ensured my department could bring him and his Latinos who Lunch co-host at their asking rate, which they then followed by featuring me on their show. Our obsession with Queer Latine TV compelled us to host a live recording at UNLV’s Marjorie Barrick Museum’s auditorium a little over a year later. When, in the winter of 2021, he told me they were going to put out a monograph* of his work called Fantasy/Fantasia together, I squealed in excitement, not knowing the editors would invite me to write about how the evolution of our collaboration and friendship shaped how I viewed his work.

Favela’s commitment and integral balance of professional collaboration and emotional investment frames his collaboration with Bertha Gutierrez-Tejada. Like Favela, Gutierrez-Tejada balanced collaborating with family and friends to bring this together. In the months before Favela moved to start working with Live in America, he and Gutierrez-Tejada talked about how he had found kinship among her gente and was looking forward to developing those relationships. Their collaboration was as much about institutional expectations of constructing and imagining inclusion as they were organically deepening their shared respect and investment in each other’s creative and political practice. Their careers and political/creative practices are invested in celebrating both their communities of origin and the communities in which they live.

Gutierrez-Tejada maintains strong family ties with frequent visits to her family still residing in Northwest Arkansas. This particular return marks the celebration of what community members have already and continue to contribute to the region to which they immigrated. In so doing, she, with Favela, sparks dialog about how to continue to promote public art visibility that supports the region's growing diversity. Walking with them as much as working with them this past May reminded me of the questions that drive my own work: What’s the work without gente? What’s the point of our work if we can’t go back or lift as we climb?

On the heels of watching Decolonizing Art History: New Works in Latinx Studies, observing and participating in this event speaks to the aesthetic contributions of Latine immigrants in regions outside of where scholars and leaders in the art world see us. Chicago born and raised, having studied Latino Studies at DePaul University, the regional and ethno-national focus complemented what I learned as an undergrad. Engaging with southern Nevada Latine studies, however, especially artists like Favela, reminded me of the significance of engaging with Latines outside of cities where Latinos have established well known and recognized cultural interventions and institutions that celebrate Latine aesthetic practices. Collaborations like Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada’s cross-regional Family Fiesta, grounded in friendship and mutually invested in pro-immigrant narratives warrant more attention. They model the need to look at aesthetic practices outside of historically recognized Latine regions as well as the potential of cross-status collaborations—Favela Vegas-born to parents of Guatemalan and Mexican descent, and Salvadoreña Gutierrez-Tejada having arrived to Northwest (Springdale/Fayetteville) Arkansas as a high school student.

I can write that now, weeks after the event, knowing I’ll want to write more about their process with attention to respecting their detail-oriented efforts and elaborating on the way they model community-based collaboration that complements what I learned as Marixsa Alicea’s research assistant during my sophomore and junior year at DePaul and what I tried to expand upon during my year being an oral historian and archivist for CENTRO’s Puerto Rican Oral History Project. At the moment, though, I was praying the truck Justin was using would survive Friday and Saturday, loading and unloading soda and the decorations we spent hours making. Good fortune found us running into Jones’ staff the Friday before the fiesta, which initiated dialog to store the cupcakes in the Jones Center fridge, considering how Gutierrez-Tejada’s mom and sister’s fridges were filled with the desserts they made for the fiesta.

But they weren’t the only ones cooking. Local Latine business owners were hired to make pupusas and tamales for the fiesta. I sampled the pupusas because the restaurant across the street had made them for the event. Walking into Los Alamos, across the street from the Live in America Residency program, I felt like I was walking into a Puerto Rican grocery store, seeing things I had seen in the mercado my grandparents took me to during my childhood summers in Arecibo. Those looks contrasted the ones I received from others at the local grocery stores while navigating Latine neighborhoods. When I asked the owner why there were so many Puerto Rican items, she explained it was because of the growing number of Puerto Ricans who moved there. She also showed me the Dominican sausages she was selling, and when I saw a recap in the fridge, I took a picture and sent it to other Puerto Rican friends. This was the Latine solidarity I had in the weekly walks I took with Favela, Gutierrez-Tejada, and others during quarantine, and it was the solidarity in which I came of age as the child of a Dominican father who came here as a teenager and Puerto Rican mom who moved here when she was eight. I felt at home in ways that reminded me I wanted to find a way back here, even as I processed the initial uncertainty and responses from confused folks hiding from the space Family Fiesta was beginning to take.

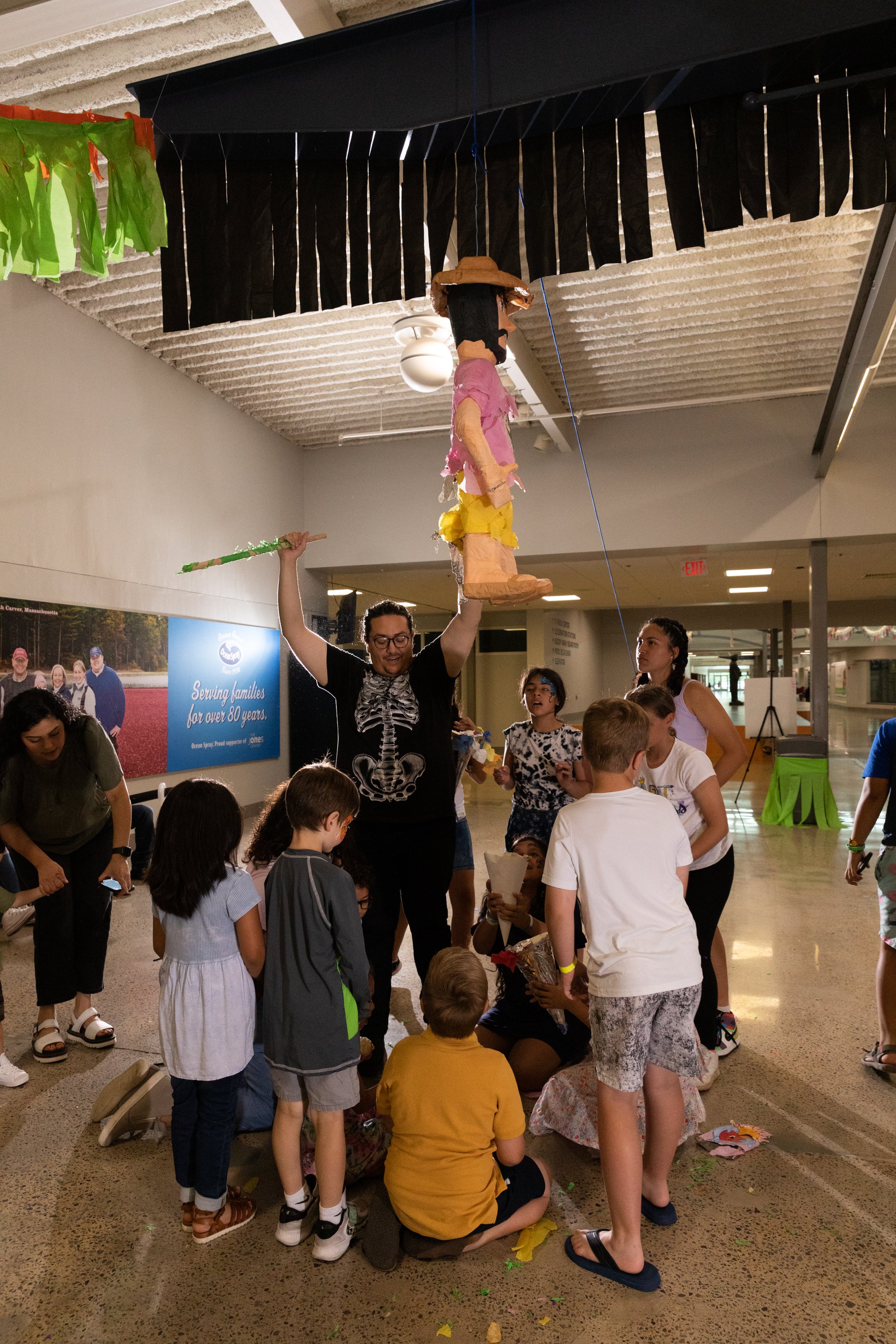

Watching Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada decorate on the day of the event while I moved tables and waited for directions, I found myself organically integrating into the performance. Passersby’s willingness to ask about the nature of our work reveals why Fiesta functioned as a powerful vehicle of intervention. Latine staff and members directly asked us why we were there, whereas white families varied in their engagement with us, one child and parent making a point not to look at us. Reading welcome signs on doors differs from feeling welcome. As supportive and encouraging as the staff had been, the engagement of members and staff told a different, more nuanced story. Still, learning how to teach people to use the tissue paper we’d prepped for a piñata and how to design their own piñatas reinforced the potential of disrupting those earlier moments. Watching children of all colors fish for Salvadoran dessert overpowered the morning of uncertainty even as they rarely talked to each other while making their piñatas. Watching Favela make sure Gutierrez-Tejadas’ sobrinos were the ones to make the final blows to shatter the piñatas spoke to the intentionality of decisions that, as I continue to write about Favela’s work, I’ll need more clarification on.

As much as I write this review because of the significance of Gutierrez-Tejada and Favela’s intervention with Family Fiesta, I approach this with gratitude, humility, and respect for what they’ve trusted me with over the years. Bearing witness to the evolution of Favela’s public art interventions, I recognize my responsibility and privilege with regard to how to discuss the work in this political moment. Given how much Gutierrez-Tejada has done for the Vegas community in which we live and the brilliance of her creative practice and professional collaboration, I look forward to catching others up on how amazing she is.

Five years ago, I never imagined artists like Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada would invest in the level of trust and collaboration they had with me. Their trust shapes why I prioritized staying in Southern Nevada when looking for a tenure-track job in the fall of 2021. Through collaborating with folks like Favela and Gutierrez-Tejada, I am finding new ways to collaborate with gente like the ones I left behind in Chicago. And like the professors who mentored me to build a research agenda around home, these collaborations remind me of the responsibility I have to support and empower those, who like Favela, Gutierrez-Tejajda, and me, remain invested in work that allows us to–whether seasonally or permanently–go back home to the ones we left behind. And, in so doing, maybe rewrite what it means not to be able to out.

—

*Justin Favela: Fantasía/Fantasy, A Decade of Practice 2011-2021 is available for purchase via Riso Riso.

Erika G. Abad is an Assistant Professor of Communications at Nevada State University since the fall of 2022. In the fall of 2022, they curated an art show titled "Two Cultures, One Family," for the Marjorie Barrick at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Prior to working at Nevada State, they were an Assistant Professor-in-Residence at the University of Nevada Las Vegas’s Interdisciplinary, Gender, and Ethnic Studies Department. They've been featured on podcasts like The Art People Podcast, Seeing Color Podcast, and Latinos Who Lunch. They’ve contributed to Latinx Spaces, Intervenxions discussing queer Latine representation on television. Since the fall of 2018, they’ve worked with UNLV’s Majorie Barrick Museum of Art, giving lectures, conducting journalistic interviews, and writing reviews on Vegas-based exhibits and artists, some of which have been featured in Settlers & Nomads, and Marjorie Barrick Museums’s Dry Heat, in addition to catalogs. They also contributed an essay to forthcoming text, Justin Favela: Fantasía/Fantasy, A Decade of Practice 2011-2021. You can follow them on twitter @prof_eabad.