Malaise of Migration: Diego Andrés Murillo’s Films

Based in New York City, Diego Andrés Murillo is not very well-known, but he is a significant filmmaker from the Venezuelan diaspora. He is one of approximately eight million people who have left the country since 2000, in his case as part of the largest wave, which began in 2016.

The South American country was the richest oil-producing state in Latin America and a stable democracy. What has happened there is similar to the effects of a war, even though no such conflict has occurred.

Despite this deterioration, the precarious situation of some migrants in their new homes, and the ongoing political upheavals in the country, Venezuelans hold on hope that the causes that drive them away will wane and that they will be able to return to their homeland. This is why the word “diaspora” is fitting to describe Venezuelans now scattered around the world.

Murillo’s short films are handcrafted, experimental works, and shown only at a few festivals. Although this limited exposure is why they are not widely known, it also allows them to explore the Venezuelan migrant experiences in a way that stands in stark contrast to media stereotypes and mainstream cinema.

We must distinguish his cinema from that of other Venezuelan diaspora filmmakers in different production and distribution circuits. For example, Lorenzo Vigas, who lives in Mexico and won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Desde allá (2015), and Mariana Rondón, who lives in Peru and won the Concha de Oro at the San Sebastián Film Festival for Pelo malo (2013). They are among those who have succeeded on the international arthouse circuit.

Within this diaspora, there is also a new, emerging wave that follows a Venezuelan industrial model, inspired by national television that gained international success. An example is Diego Vicentini’s Simón (2023), a film about student resistance against the regime.

Murillo's cinema is distinguished by its work with sound and image to recreate, in a sensory way, the unique experience of space and time for those who live outside their country, yet constantly communicating with family and friends back home through voice messages such as those on WhatsApp.

This is something his short films share with Luis Alejandro Yero’s Llamadas desde Moscú, (2023), a Cuban feature that has toured festivals. A more widely known, though distant, reference is the voice-over reading of letters in Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1976).

Murillo’s ability to express his discomfort as a Venezuelan and as a migrant is also striking. He is authentic about this, even at the risk of not being understood by those who believe people like him should feel happy and grateful to the nations that receive them. His short films thus refer to another feature film by filmmakers from Cuba: A media voz (2019) by Heidi Hassan and Patricia Pérez Fernández.

Discomfort turns into furious rebellion in Murillo’s most recent short films. In this way, they perform an identity that can be problematic for those who, due to prejudice, fear migrants’ anger and may even associate it with terrorism. Perhaps this is currently hindering the circulation of his films.

In Antílope (2019), the first short film he made abroad, there is constant communication between the United States and Venezuela through voice messages. This creates, in the story’s present, another timeline that flows to the past, the “situation” left behind by the departure—a decision that involves searching in the opposite direction, toward a better future.

That other time, from another place, can break at any moment. Although the migrant is free to ignore messages from home, as the short film’s protagonist does, the soundtrack conveys the call of blood—a family in trouble summoning its own.

This tension is subtly embedded in Antílope’s cinematic genre of psychological horror. Symbolic elements connect the story to a descent into hell. The dog that follows the protagonist serves as an ominous presence. The young woman’s interest in the whales on television connects their mournful song to the painful phone calls she receives. The title clarifies the analogy between the solitary migrant and a prey animal, harassed and frightened in New York.

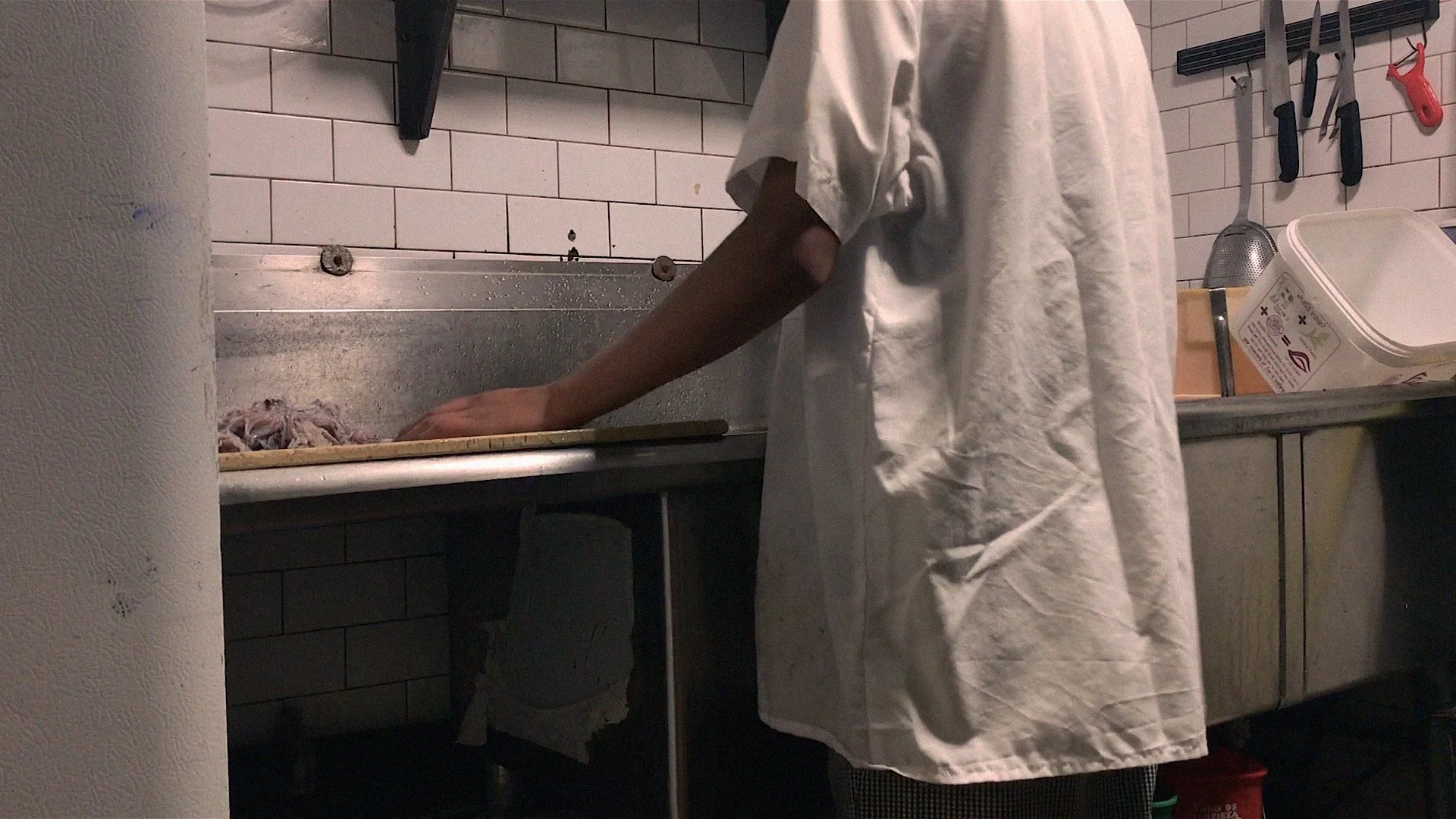

Realistic details convey this unpleasant, frightening atmosphere. There are transportation failures, workplace abuse, the predatory colleague who suggests sex work, and, above all, loneliness and exhaustion at home. Oppressive framing highlights the similarities between the house, the restaurant where she earns her living, and the entire city, to which she does not belong.

The timeline of someone seeking a better future becomes circular, trapped in a weary routine—a present that endlessly repeats itself. At this point, phone messages from home pull her back. These messages not only confirm the ongoing crisis in Venezuela—another circle—but also bring news of illness, madness, and death, opening the mouth of another hell.

There is a shift toward experimentation in Murillo’s next short film, Este no es mi reino (2021). It is a documentary in which, in the first part, time and space are tensely constructed, as in Antílope. However, image and sound develop in parallel without a phone scene to connect them. The relationship between New York and Venezuela becomes abstract, as in News From Home.

Tal vez el infierno sea blanco (2022) marks the beginning of Murillo’s more radical approach to film form. It is a hybrid work, combining archival film, autobiography, documentary, fiction, and experimental elements. It introduces a new key component: the poetry of José Ignacio Calderón, also known as Luis Lapiña.

With a poem read in a rough voice, distorted by low audio resolution, the film continues the Venezuelan tradition of expressing unease and rage toward the city of Caracas. It follows the legacy of Asfalto infierno (1963) by Adriano González León, member of the avant-garde group El Techo de la Ballena, among others.

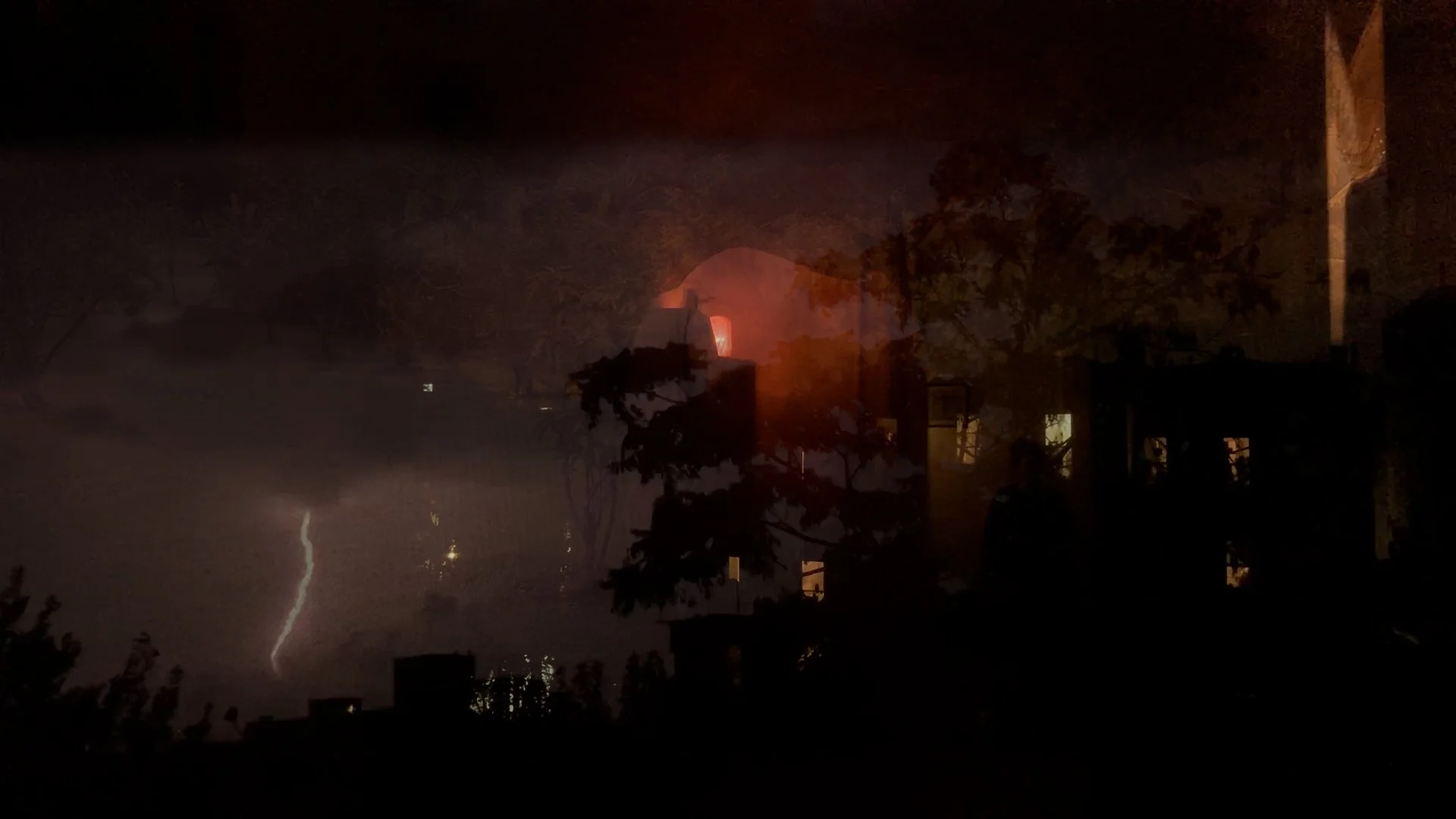

The problematization of the relationship between the territories is intensified in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown in Caracas and New York. It also reflects a past that, like the present crisis, projects itself by erasing the future where the migrant’s dreams are meant to come true.

Murillo and his partner’s visit to Venezuela is extended indefinitely. Caracas, the city of the country that “sank,” as the narrator says, appears ghostly in superimpositions in black-and-white photographs. There are also color snapshots from the family archive, fragments of better times for both them and their homeland. However, messages detailing illness and death in Venezuela disrupt those memories.

The black-and-white video images reveal the future awaiting the family in Venezuela. The mother is its heart. We see her lovingly trimming the grandmother’s nails in a nursing home. But there are blurry photos that reveal the presence of ghosts. They are omens of the final message, which again sets the call of the past—of blood and home—against the time spent as foreigners in the United States.

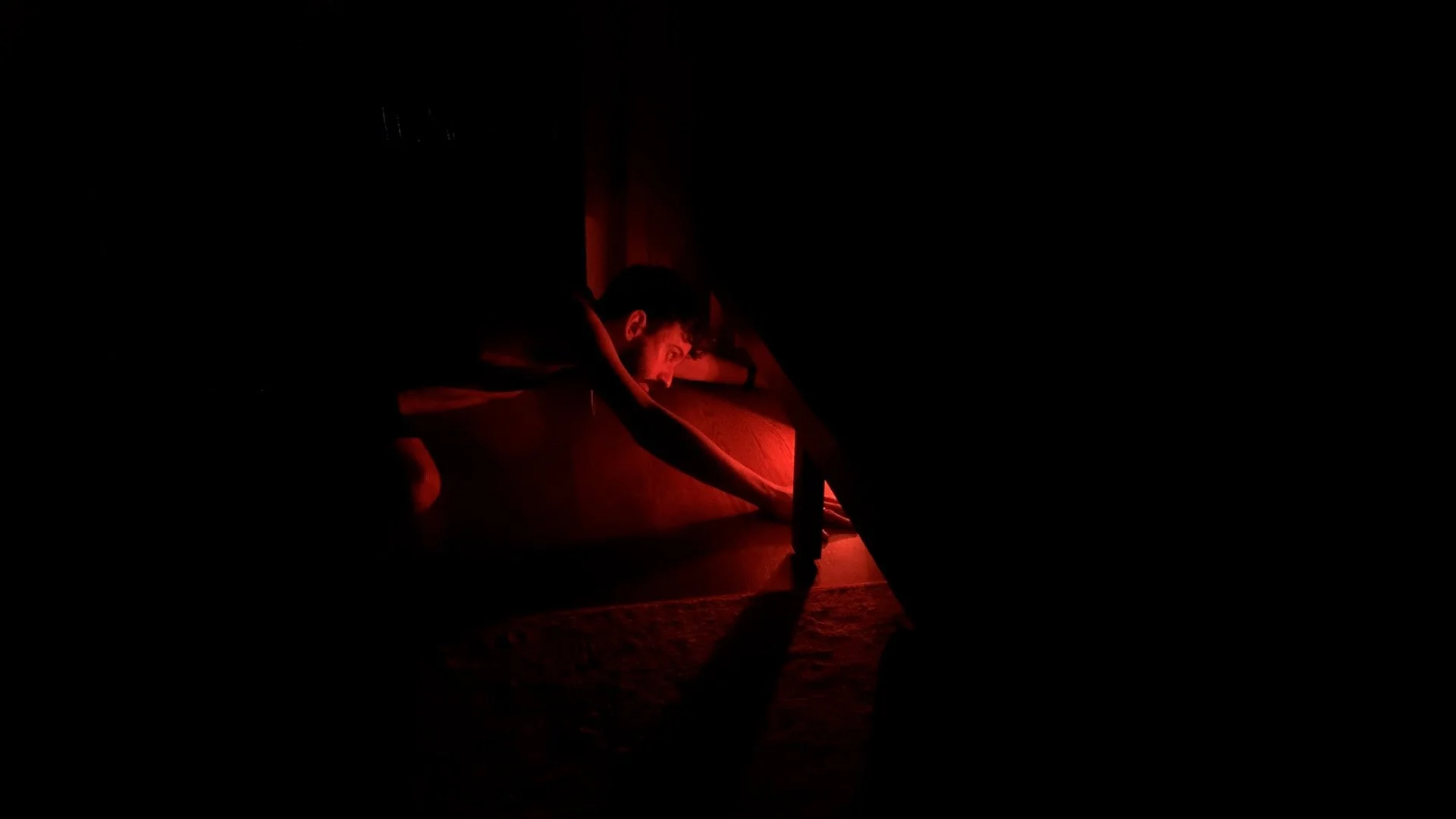

Another character in the film is a Colombian whose teacher called him “a thief” as a child. It is a story of Venezuelan xenophobia told in a scene where the power goes out, and no one seems to care. This is a realistic detail: Power outages are an everyday occurrence, especially outside Caracas. However, the outage signals another ghost, something linked to a different lamp in New York, in a mind-bending color sequence about the quarantine that calls back to Italian horror movies.

The sense of reality also wavers when going beyond the tension between visible space and voice messages, encountering the deceptive visual continuities of editing and superimpositions. Caracas and New York follow one another seamlessly and merge in the shots, as if forming a single spectral space.

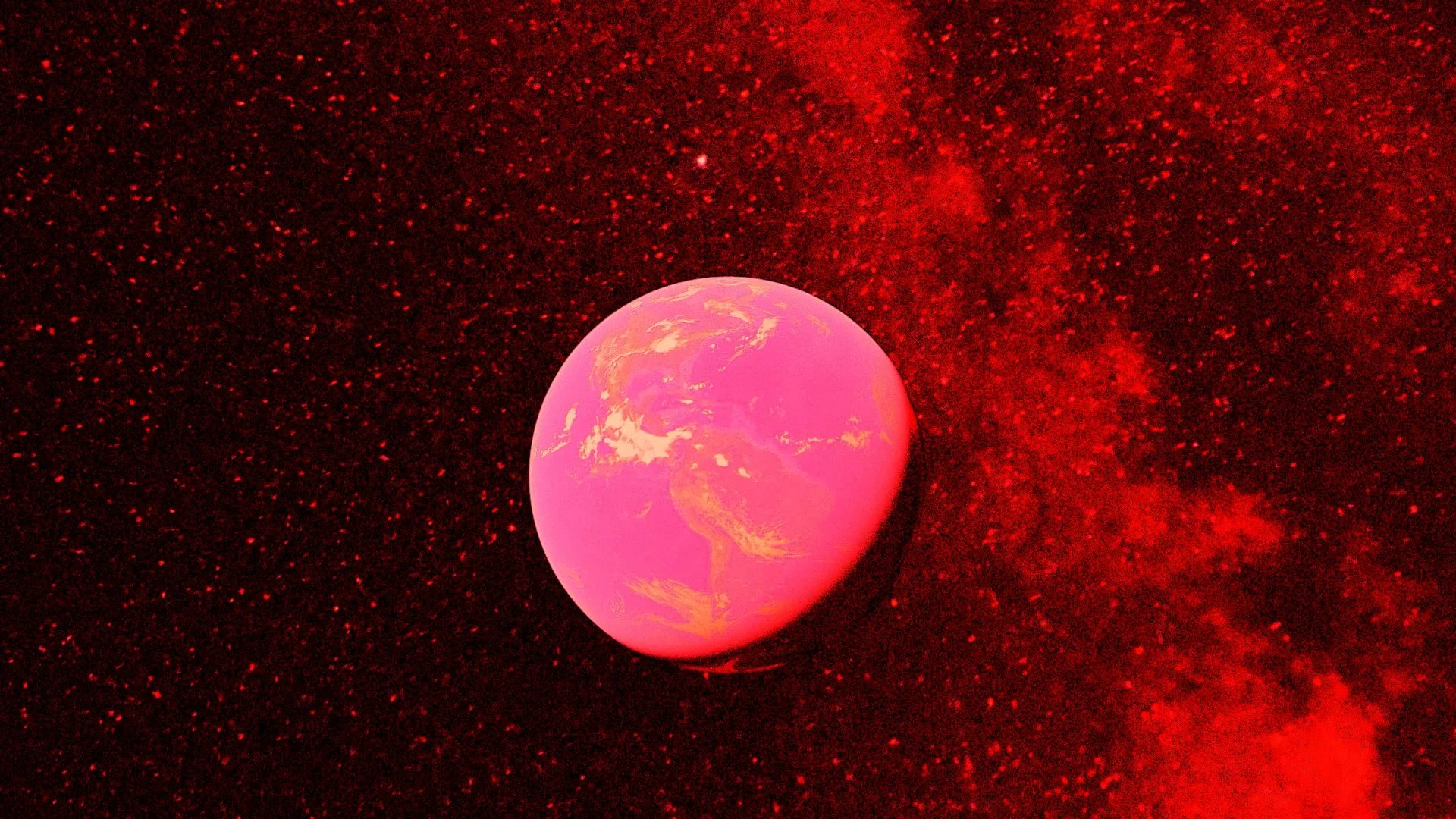

The union of these territories is like that of fire and snow. Destructive flames burn, and an icy death covers everything. The Antílope symbols are left behind. Here, we feel as if we’re lost in a nightmarish hell.

In Malestar transatlántico (2023), Murillo addresses issues that affect migrants’ ability to make films, similar to those faced by the filmmakers of A media voz. The difference is that it is not presented in a testimonial and reflective manner. Instead, it is delivered with rabid, furious sarcasm, through a message sent by a character from the future, as in the previous film.

Murillo made the film at the Locarno Festival’s Spring Academy, working with footage from Swiss archives. However, instead of showing gratitude and compliance to the Europeans who gave him that opportunity, he again expresses his discomfort as a migrant.

The short film addresses the perception that people abroad may have of the Bolivarian Revolution. It is a reaction to the desire for utopia in other places where comfortable living is possible. The real suffering of those in countries like Venezuela is justified and tolerated in the name of such foreign dreams.

Murillo recovered a fragment of President Hugo Chávez’s 2013 funeral as shown on Swiss Italian television. He mocks the depiction of grieving Venezuelans by juxtaposing it with a fleeting shot that presents a different image of his people, a furious malandro firing his gun into the air. The work also contrasts what Venezuela represents for the Swiss with how Italian speakers in Switzerland perform their cultural identity on a national TV channel.

The editing confronts the white, snow-capped mountains—a stereotype of the “Swiss landscape”— with close-ups of a sewage stream. In Spanish, these streams are aguas negras (black waters). The narrator in the film—a fake diary written on the screen—suddenly suffers the malaise of the title. It is like a mysterious illness he contracts in a country that, for Venezuelans, is almost paradise, as if it were instead a foul place. Poetry appears among the symptoms.

Malestar transatlántico takes irreverence even further. The story is nonsensical: a secret agent in the future, sent by the Venezuelan regime to find a film of Hugo Chávez’s birth, supposedly kept in a Swiss archive. The corrupt regime provides the agent with a clip from a pornographic film featuring the sons and daughters of the European country’s foreign minister. They give him this so he can obtain more material through blackmail.

However, due to the same dishonest and erratic modus operandi, his superiors in Venezuela declare the agent a traitor to their nation after having access to the diary. As a result, the protagonist is left in limbo, a sarcastic version of deterritorialization—someone who has no place to go and no country to return to.

Faced with this, we read a phrase whose origin may be Murillo or the archive: “The images will bring me closer.” It expresses a desire to feel close to home, but it is also ironic. He could find that text about closeness among the images with which he constructed a story of unhealthy detachment that ends in exile.

Malestar transatlántico marks Murillo’s cinematic transition to the performativity of a migrant identity, moving from discomfort to openly expressing discontent and rage—emotions that can be particularly upsetting when associated with migrants. However, this same furious impulse also works against the piece, causing it to lose cohesion and coherence.

A new, distorted voice, similar to the one previously heard at the end of the extended version of Este no es mi reino, is present in Murillo’s most recently released short film, Te seguimos buscando (2025). Here, the work again engages a literary source, the poem Introducción al símbolo de la fe (1970) by the exiled Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas.

The poem’s theme is the Cuban homeland, and there is a shift from the diaspora to Venezuela in Murillo’s short film. Notably, it begins with close-ups of a crystal-clear stream, evoking a contrast with the dirty stream in the opening sequence of Malestar transatlántico.

Comparing our country to Switzerland is common in Venezuela. There is a colloquial expression, “We’re not Swiss,” that highlights our imperfection. This aspect of national identity is evident in the short film, where the narrator himself acknowledges editing flaws. Murillo thus embraces “imperfect cinema,” valuing commitment over artistic rigor.

Work with the archive continues with a United States Information Service piece on President John F. Kennedy’s 1963 visit to Venezuela and Colombia. The two countries blend seamlessly in the images, ironically conveying the lack of distinction for the foreign institution that produced the film and perhaps also for viewers from neither place.

There are times when art can be unexpectedly prophetic, and that is the case with Te seguimos buscando. The combination of Arenas’s text and Kennedy’s film, distorted in various ways after the bombing and kidnapping—officially “extraction”—of Nicolás Maduro by the very United States that arrived with the message of peace and goodwill from the Alliance for Progress, seems tailor-made for the current situation, even though it was not.

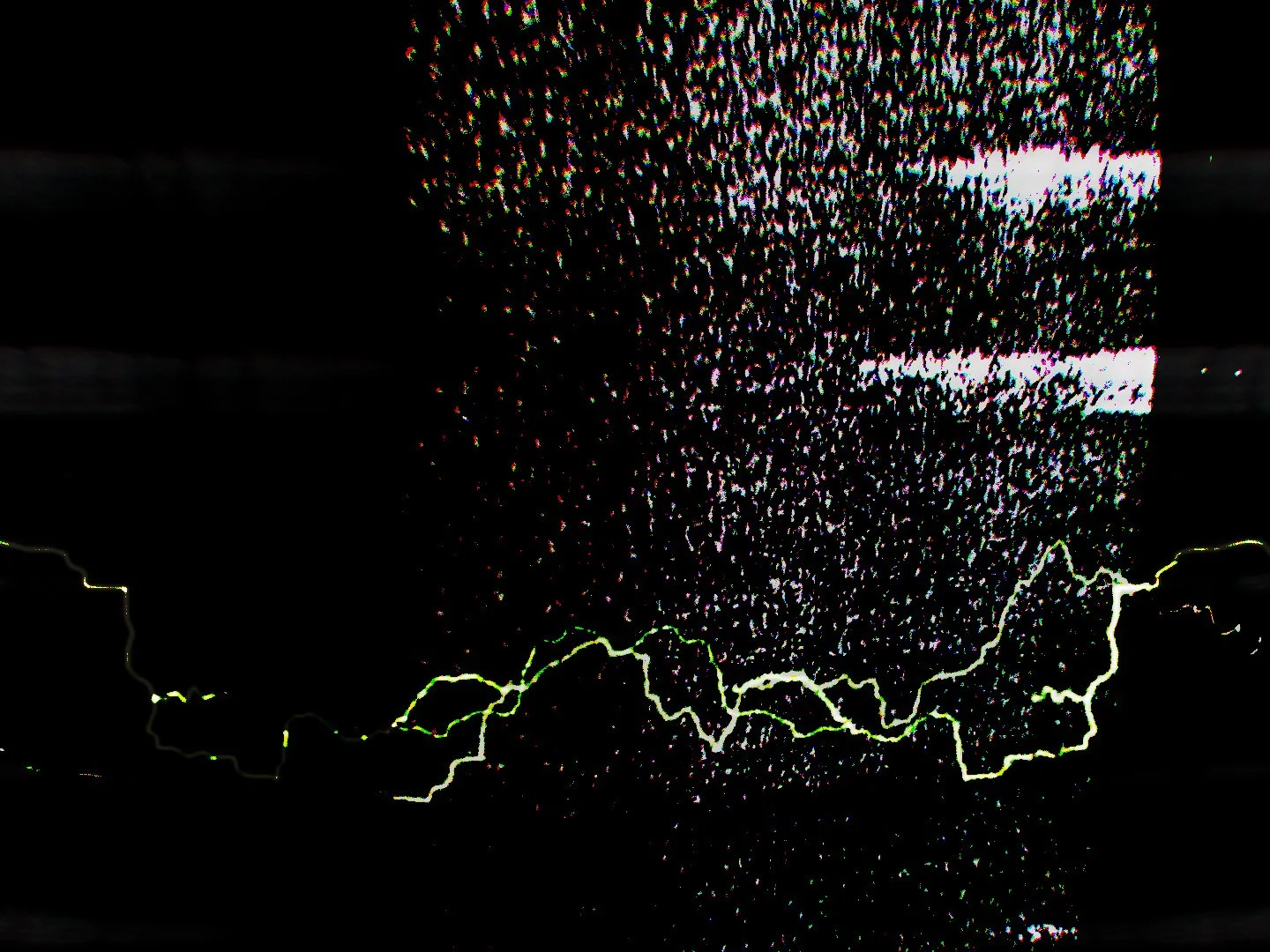

The ending opens the fate of the homeland like an abyss, with a sequence of audiovisual noise. It is exactly what one might expect from the Venezuelan’s rage, which ironically invites the viewers to let themselves be carried away by this part of the film.

A possible future national identity takes shape so terrifyingly in this film’s invocation of the homeland, precisely because there is no longer a homeland to invoke. The migrant’s rage thus mutates into sadness, a feeling the narrator makes explicit at the outset, just as Tal vez el infierno sea blanco introduced the word “discomfort.” Once again, it is the performance of a migrant identity that does not reterritorialize, that finds no place in the world except the one it has lost—the one destroyed—and can feel nostalgia only for ruins.

There is an epic and dramatic myth of the faith that drives migrants to fight for a better future, but there are few who dare to confront real suffering with such passionate lucidity as Murillo. Those who persecute migrants fear peering into their own abysses, from which emerge the ghosts that drive them to hatred.