The Political Economy of Covering ICE

On August 21, 2025, an SUV on the 210 freeway in Monrovia, California, fatally struck Roberto Carlos Montoya Váldez, a 52-year-old immigrant from Guatemala. Váldez had been looking for work as a day laborer at a Home Depot but fled during a raid by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers and was killed in the process. In Los Angeles County, which is predominantly Latinx, the increased presence of ICE has raised significant alarm amongst the city’s residents.

Since 2025, ICE has more than doubled its workforce and has acted with relative impunity. Earlier that year, the U.S. Supreme Court gave ICE the authority to conduct administrative arrests based on reasonable suspicion or probable cause. Armed with this power, ICE has aggressively raided where Latinx communities work, shop, and eat, often with disregard for human rights.

In response, several Los Angeles–based newsrooms have been covering ICE activities. Some news organizations have directed significant resources toward recording ICE agents’ misconduct and abuses of human rights, while other news organizations have approached the topic in limited or dispassionate ways. To understand the kind of journalism in which a newsroom can engage, it’s helpful to think about journalism from a political economy framework, which accounts for how a media organization’s structure, including ownership and finance.

A combination of memberships, donations, and the patronage of wealthy, invested donors like Eva Longoria fund the site. Founded in 2006, L.A. Taco is a multimedia platform that originally covered culture and lifestyle. But according to editor-in-chief Javier Cabral, its mission changed in response to the tepid coverage of the local press. “One of the biggest challenges of being a journalist is being able to operate and perform our duties without letting our emotions get in the way,” Cabral writes in an open letter to readers. “At the same time, one of our biggest strengths as writers is our ability to utilize any emotion, whether rage or sadness, to fuel our writing.”

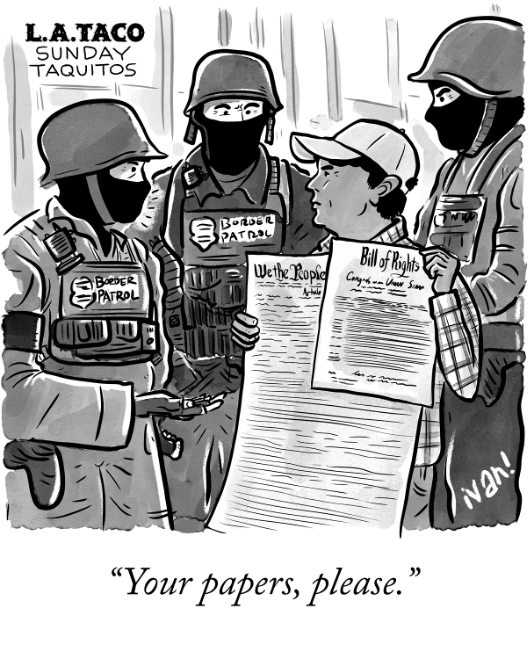

More than covering ICE activities, L.A. Taco has decided to educate Latinx communities on their rights and provide resources for responding when contacted by ICE. On July 21, 2025, LA Taco ran a piece titled “What to do if ICE comes knocking.” The piece gives readers a set of recommended practices: Do not open the door to a home or a car; do not sign anything; ask to speak with an attorney; and have your papers organized and accessible.

L.A. Taco is not the only news organization conducting this kind of labor on behalf of Latinx communities. The LA Local—a small nonprofit newsroom dedicated to journalism in Black and Latinx neighborhoods—has reported extensively on ICE activity, particularly its impact on local businesses and how community organizations and leaders are fighting back. LAist, an independent nonprofit newsroom and home to NPR member station 89.3, has published a resource guide to educate readers on what to do if a loved one is in ICE custody. It also provides hotlines for reporting ICE encounters and information on low-cost legal support. Journalist Julia Barajas wrote a piece for LAist informing readers about their civil rights, regardless of immigration status.

In Reporting on Latina/o/x Communities: A Guide for Journalists, Teresa Puente, Jessica Retis, Amara Aguilar, and Jesus Ayala Rico detail how Latinx communities have been a part of the U.S. since before the annexation of Mexican and Puerto Rican territories in the mid-to-late 19th century. Yet, new organizations continue to underserve Latinx communities, despite their longstanding presence. In Los Angeles, Latinxs were perceived as a conquered people even before the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and were subject to continuous marginalization, including land dispossession and violence.

Latinx-owned newspapers emerged to meet the needs of these communities. For example, El Clamor Público was established just seven years after the annexation of California. According to Nicolás Kanellos, the Brown Foundation Professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Houston, El Clamor Público has the distinction of being Southern California’s first Spanish-language newspaper, run solely by a native Latinx Californian, serving his local Spanish-speaking community. Francisco Ramírez, the paper’s editor, spoke out against the violence committed against Latinxs and challenged the state and federal laws that ensured the dispossession of Californio lands. But like other small papers of its time, El Clamor Público was in a financially precarious position and closed after just four years.

Several short-lived Spanish-language publications, including La Prensa, El Heraldo de Mexico, and La Gaceta de los Estados Unidos, were part of the Spanish-language press that emerged in the early 19th century. The longest-standing publication, however, has been Los La Opinión, established in 1926 by Ignacio Lozano, a Mexico-born publisher. For much of its history, the publication has been a family-owned business, and it focused on serving the city’s Latinx population, predominantly new immigrant Mexicans.

The importance of the Latinx press becomes evident during moments in which there are state-sponsored efforts to antagonize Latinx communities. During the Great Depression, the Hoover administration launched a series of attempts to forcibly deport almost two million Latinxs, many of whom were deported without due process. A comparative study that Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Ricardo Chavira conducted found there were significant differences in how La Opinión and the Los Angeles Times, the city’s flagship newspaper, covered deportations. According to Chavira, La Opinión took a more human-centered approach, focusing on the impact on those who had been deported. It wrote about the many repatriates arriving in Mexico with almost no money or clothes. They were hungry and became ill during the process. It was reported that there were 30,000 repatriates who were unhoused.

By contrast, the Los Angeles Times described these forced deportations as voluntary. “Mexicans to Leave for Home,” read one headline from October 29, 1931. Furthermore, the Times attempted to distance its readers from the human cost of the repatriation efforts by reducing the campaign to its economic impact. “The exodus has saved the taxpayers about $2,000,000,” the Times wrote in 1933. “That would have been spent in caring for these destitute Mexicans.” The Times’ deportation coverage is not necessarily surprising. The Los Angeles Times was a Republican newspaper owned by the wealthy Otis-Chandler family. Furthermore, the family held a particular antipathy toward Latinxs and had a history of referring to them as “wetbacks,” “half-breeds,” and “peons.”

Today, federal officers are systematically detaining and deporting Latinxs, without regard to citizenship status. While there are some striking parallels to the repatriation efforts of the 1930s, there are also significant technological, economic, and cultural changes that have impacted journalistic practices. Furthermore, the Los Angeles Times is not the same organization that it was in the early 20th century. It has reflected on its past practices and is engaging in a more reflexive kind of journalism. Furthermore, an increased Latinx presence in its newsroom brings new insights and sensibilities, which shape how the publication covers Latinx communities.

Most importantly, the paper’s economic realities have changed. The Los Angeles Times operates in a city that is 48% Latinx, which means they are no longer seen as an impediment to economic progress but rather as a prospective audience that is essential to the publication’s future well-being. To serve Latinx communities, the Los Angeles Times has created several dedicated properties, including De Los, which includes a multimedia platform designed to serve young, acculturated Latinx readers, and the Latinx Files, a newsletter produced in English.

These various platforms cover the Latinx experience in nuanced and multi-faceted ways. Furthermore, compared to much smaller newsrooms like L.A. Taco, the Los Angeles Times has significantly more resources, which allows it to cover ICE extensively, and it does so in a multifaceted approach: through its columns, editorials, and its Latinx-dedicated platforms. For its coverage of ICE, the publication won the July Sidney Award, which the Hillman Foundation gives to journalism that exposes social and economic injustices. “The LA Times coverage shows the power a local newsroom can have on a national story,” July Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein says in a press statement. “The LA Times is on the street documenting the terror of the raids and the far-ranging fallout of Trump’s policies and offering a chilling preview of what may lie ahead for other cities.”

Beyerstein is implicitly describing the ability for large-scale, mainstream newspapers to engage the majoratorian public sphere. Still, large, national newspapers are subject to different kinds of political and economic pressures, which limit the kinds of coverage in which they can engage. They can cover ICE, but they do not necessarily serve as advocates for Latinx communities. Jack Herrera, a national correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, addressed this issue in an essay he wrote as guest editor of the Latinx Files. Herrera described his conflicting feelings about Univision, which had given a friendly interview to Donald Trump. Herrera’s first inclination was that Latinx communities would consider that decision as a betrayal. But as a journalist, he felt that there might be conservative Latinxs who would support the decision. For Herrera, being a journalist means striving for objectivity in pursuit—however uncomfortable that truth may be.

Herrera’s words reflect the fetishization of “objectivity,” which has become a commonsense belief within the journalistic community. However, this kind of dispassionate coverage is not what the moment calls for. Nor is what Latinx communities need. There is a need to do more than document events; journalists must educate, inform and mobilize. Furthermore, the “neutral” stance journalists take can obscure rather than reveal. For its part, L.A. Taco is clear about its orientation, apparent through its unabashed use of language. “ICE Kidnaps Parents from San Bernardino, Riverside, and Orange County the Day Before Christmas Eve,” reads one headline. While the use of terms like domestic terrorism, kidnapping, and abductions may seem to go counter established journalistic practices, they can be the most accurate terms to describe a phenomenon. In an interview with the CBC, Cabral pushed back against the notion that such use of language was not sound journalism: “When you just see constant repetitions of very violent federal officers who refuse to identify themselves. Who cover their faces and just show up and abduct you and detain you, call it whatever you want.”

These are the kinds of journalistic practices in which large, mainstream news organizations are not inclined to engage. But they are, nonetheless, necessary. Herrera conceded this point, suggesting in a healthy media ecosystem, a diverse set of newsrooms with different approaches, funding models, and mandates serves these communities. “At many publications — certainly at this one, and at Univision — you’ll find journalists debating the philosophical question of objectivity, getting to its root and trying our best to get our readers the most accurate and useful version of what’s going on,” he writes. “But why any publication decides to take any specific stance on objectivity, and to market itself as balanced or partisan, often comes down to a question of money, more than we might like to believe.”