Tijuana Ayisyen: The Haitian Diaspora in Film

The political imaginary figures migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border as brown children and adults carrying their livelihood in backpacks and plastic bags. These images reinforce a racial stereotype, as well as erase the experiences of others. Absent from these discourses are Black migrants, particularly considering the mass displacement of Haitians. Three documentary films—Ebony Baileys’ Life Between Borders: Black Migrants in Mexico (2017), Sam Ellison's Chèche Lavi (Looking for Life) (2019), and Tim Ouillette’s Waylaid in Tijuana (2020)—center the lives of displaced Haitians in the U.S.–Mexico border region, namely Tijuana, Baja California.

These movies capture the formation of a Haitian Tijuana in the framework of a transborder racialization process. As Haitians waited in suspense for immigration officials to take up their cases, they formed vibrant communities rooted in mutual forms of care with limited resources.

Despite these xenophobic and racist attacks, Haitians reconfigured a cultural Tijuanense landscape unfamiliar to Haitians. In the three films, the scenes of a Haitian Tijuana include culinary exchanges, physical movement and exploration throughout Tijuana's cultural landmarks, economic survival through employment in local establishments, and finding a sense of joy despite living in crowded shelters. In essence, this transformation included reflections and discourse on anti-Black sentiments. Haitian transnational community formation and creative means of survival amidst the challenges of institutional and cultural barriers is an aesthetic of Haitian Tijuana resilience and community.¹

The earthquake that rattled just west of the capital city of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on January 12, 2010, became a metaphor of the centuries-long political and social instability on the island. And the disastrous humanitarian aftermath foreshadowed the further deteriorating conditions in the decade to follow.

As displaced Haitians left their homes for economic opportunities throughout South America, like in Brazil, others filed petitions for asylum in the United States. During this period, the Obama administration removed more than 400,000 migrants, refugees, and displaced persons in June 2010. In shattering a stunning record of deportations, the administration architected a xenophobic behemoth in the immigration-industrial complex, laying the foundations for the latent right-wing nationalist sentiments, stringent immigration policies, and state violence on racialized bodies that would follow the 2016 election. Five years after the disaster, the United Nations declared 2015 the year of mass displacement.

In 2017, the U.S. government terminated protections for Haitians. As incarcerations and deportations of racialized migrants and refugees alarmed advocates of displaced peoples, documentary films such as Ai Weiwie’s Human Flow (2017) introduced to spectators a new regime of militarized state violence in the making amidst the surge of right-wing nationalism. Photography, footage, and visual art narratives of displaced persons intensely proliferated, including those of the Haitian experience in the Americas.

One need not look too far back in history to recall that U.S. authoritarian leaders have endangered the life of Haitians at the border and within the U.S. through discursive violence. For instance, during the 2024 presidential campaign, extremist right-wing candidates Donald Trump and J.D. Vance helped amplify fake narratives that Haitians abduct and eat missing pets in Springfield, Ohio. Furthermore, in 2021, footage of Customs and Border Protection agents on horseback seemingly whipping Haitian migrants in the Rio Grande amplified anti-Blackness in the immigration system.² Once again, the visual history of slavery emerged through the specter of the plantation overseer in the form of an immigration agent. Studying film and media on the experiences of displaced Haitians is resourceful as documentary cinema indexes the evolving transborder racialization and discourse around Black immigration.

The images of state-sanctioned violence against Haitians in 2021 at the U.S.-Mexico border revealed the state’s calculated distribution of conditional admittance and hospitality. According to professor and author Mireille Rosello, hospitality is contextual, with varying interpretations at the discretion of the state. In Postcolonial Hospitality: The Immigrant as Guest, Rosello writes, “voices seeking to resist the inhospitable dictates of the state often find themselves caught in double binds and contradictions that are very difficult to translate into daily tactics.”³ For Haitians attempting to enter the U.S., experiencing inadequate living conditions in Mexico subjected them further into a cycle of inhospitability.

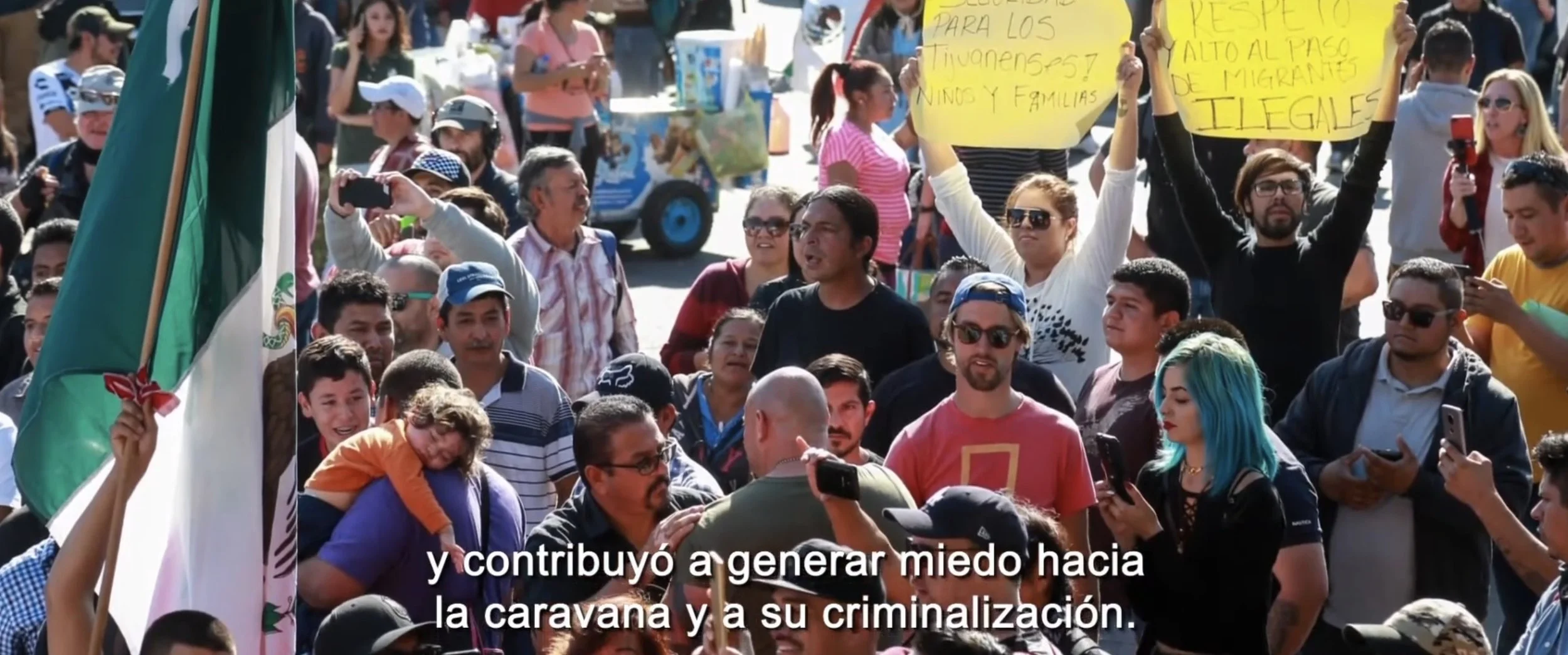

The three documentary films depict how the U.S. and Mexican state both produce varying degrees of inhospitability via discourse production. For instance, in the film Waylaid in Tijuana, Paulina Olvera, director of nonprofit advocacy group Espacio Migrante, explains that the noxious rhetoric of the 2010s in the U.S. mainstream press traveled south of the border.

“One thing that I saw that was different with the caravan in November was the negative media and also the negative discourse by our local authorities in Tijuana and that echoed the Trump narrative,” Olvera says in the film. Confirming Olvera’s observation, the filmmaker inserts footage of then-mayor Juan Manuel Gastelum regurgitating U.S. xenophobic talking points: “Look, it is a guarantee that we have, as Mexican citizens, that anyone who arrives in a disorderly way must return to their place of origin. And this is the message, because here in Tijuana, we are a hardworking city.”

Though Gastelum’s acrimonious remarks concern the Central American caravans, these sentiments carry racist undertones duplicated from language in the U.S. The mere idea that a laboring migrant body deserves humanitarian assistance is quixotic and ableist.

The border is viewed as a hybrid and dynamic space of trauma and possibility, as described in the words of Chicana author Gloria Anzaldúa.⁴ The racialization processes and fear of migrants is a logic of settler-colonial fears of changing demographics.⁵ Further, scholar Tiffany Lethabo King’s research of the relational history between slavery and immigration, in what she calls “the afterlife of slavery,” is a reminder that in the Americas, people are racialized into three categories: “the slave,” “the racialized migrant,” and “the citizen.”⁶ Moreover, Lethabo King writes, “The slave and racialized migrant are hounded to death . . . to extract status, wealth, inclusion, property, and life years so that they can be accumulated and distributed to the citizen.”⁷

In the film Chèche Lavi, a displaced Haitian reminds spectators of the long colonial and imperial violent plague that has historically destabilized Haiti. “The authorities shouldn’t forget,” he says. “I won’t focus on history too long, but we were occupied by Americans and colonized by France. A lot of talk isn’t helpful.” In referring to the assistance the U.S. government claims to extend to migrants, the film calls attention to the dire situation, rendering visible a Haitian Tijuana in formation as the community is left in the periphery.

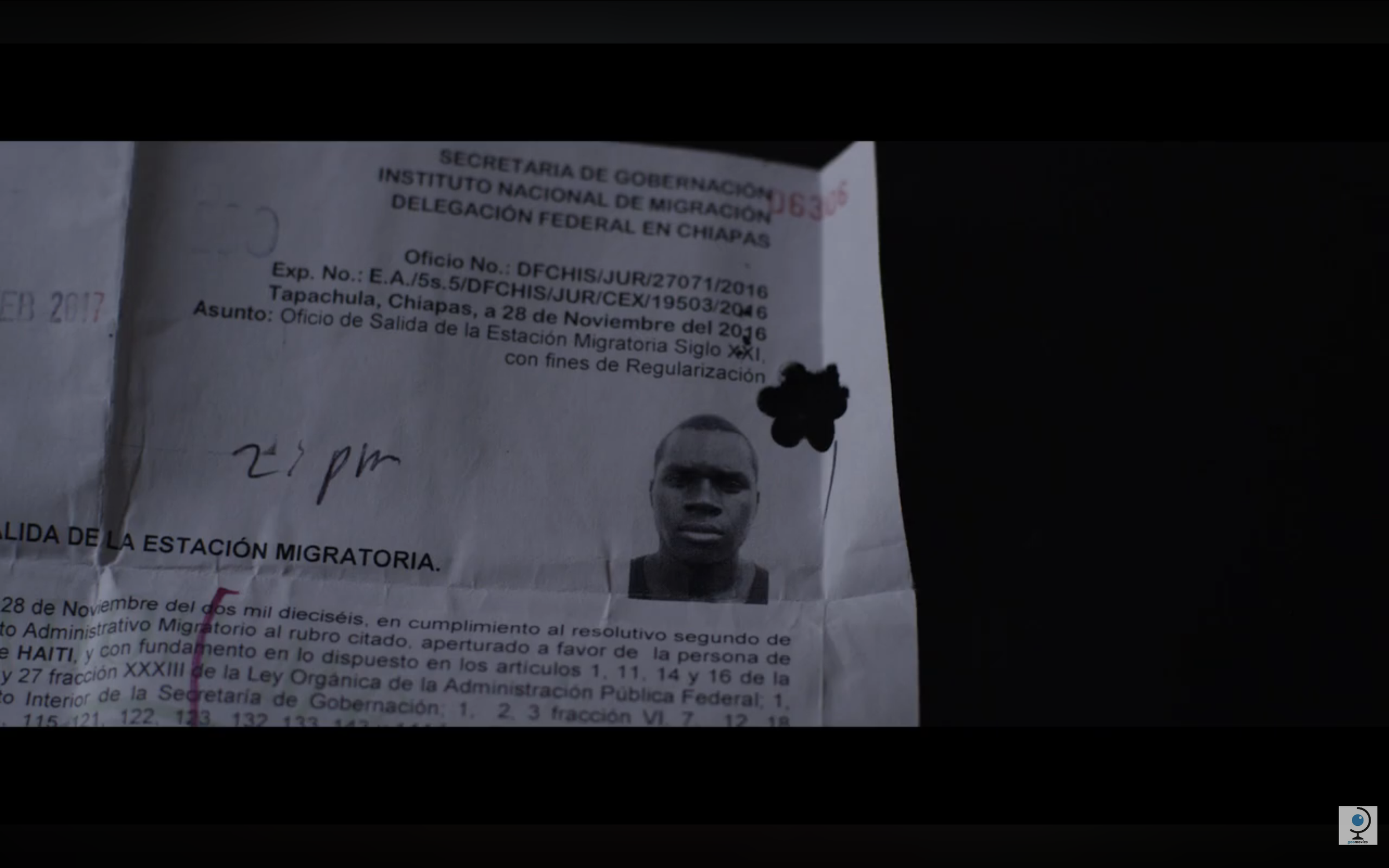

On two different occasions in Chèche Lavil, close-up shots focus on legal documents. Though not the subject of the documentary, the paper-based, government-issued documents show the abstract legal process that contain displaced Haitians in liminality. The first clip shows a document in Spanish with the picture of a displaced Haitian man. In essence, a paper mediates the survival and right to mobility that determines life and death. In the second instance, a man holds a stapled packet that reads, “Requirements for Humanitarian Visa.” This shot captures the state’s maintenance of administrative performance on eligible humanitarian status and hospitality.

A shot centers one of the protagonists of the documentary as he occupies the foreground. Behind him, Friendship Park appears prominently. This park has been the site of encounter—friendly, violent, festive—where families divided on both sides of the border speak across the rusty, metallic barriers. In a later scene, Robens holds a paper with his identity numbers that he must furnish to Mexican authorities so he can proceed to the asylum interview at the embassy.

The inhospitable environment in Tijuana as a result of draconian U.S. immigration policies and misinformation campaigns in Mexico makes for tenuous conditions for Haitians. Yet, it is the resilience, the network of Haitian-displaced persons in search of livelihood, and opportunities to be recognized as human that makes for a unique Haitian Tijuana.

The expressions of inhospitability toward Haitians is a direct result of the racial anxieties that materialize because of nationalist, capitalist resource scarcity. Haitian survival in Tijuana is imperative, part of the city’s multicultural and multiracial fabric and history. However, this requires a critique against forced integration that diminishes the Haitian experience with trauma and longing for stability. For Haitians who secure shelter in and around Tijuana, integrating into a social life that they are not familiar with can become an alienating experience. The three documentary films show that acculturation is not possible in the broader designs of Mexicanidad, or Latinidad, which exclude people based on race, language, and citizenship status.⁸

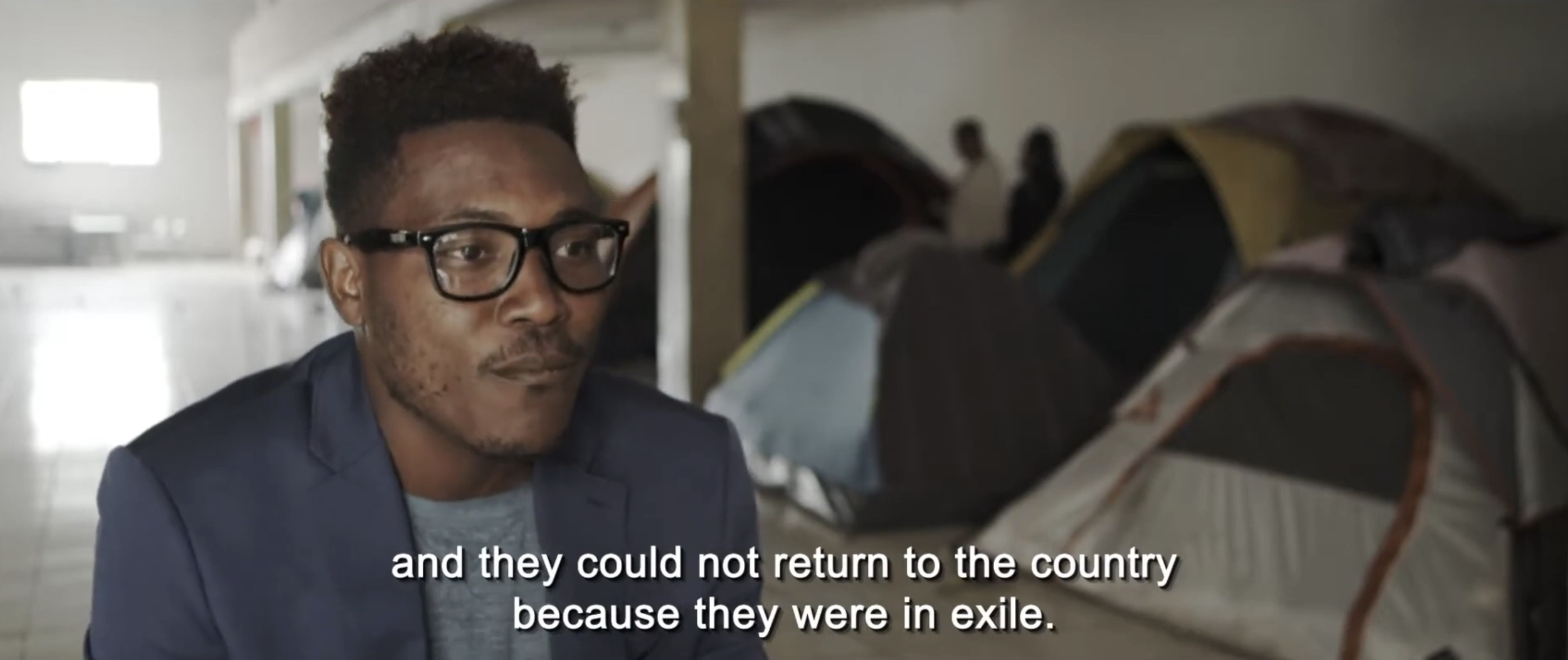

The three films do not romanticize acculturation. Rather, these visual texts identify the barriers of social class and citizenship status that inform how Haitians establish community. In the films, Haitians detail their reasons for leaving their island. For example, in Waylaid in Tijuana, one of the displaced Haitians, Bertrand, explains that his status in political exile shapes his journey that consequently determines his mobility and migration status. Bertrand relates his fleeing due to his parents having served major roles in the party of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as legislators and ministers of education. Bertrand demonstrates that his family’s affiliation branded him as a political opponent amidst the shifting politics of the country, thus endangering his life.

Though Haitians in the films express a strong desire for family reunification in the U.S., they are cognizant of the sobering realities of the stringent immigration policies limiting migration from the Global South. For Haitians unable to cross over, there are few options. Nevertheless, they explain their eagerness to pursue an education and work in Tijuana.

In Life Between Borders, a man named Emmanuel, speaking before the camera in a mix of Spanish and Portuguese, discusses his contributions in Tijuana as a displaced person. His work consists of coordinating meal preparation at a migrant shelter. A former teacher of mathematics, physics, and chemistry, Emmanuel explains, “I just want a better life. I can do any job.” Another Haitian migrant in the same film, Renat, says he wants to pursue a career in civil engineering: “I want to study a profession because I still want to cross to the other side. But if I stay here, I want to study.”

These desires to work and apply their skills beyond the exploitative service industry illustrates that there are limits to the expectations for migrant acculturation. A precarious migrant status contributes to this process. What these two seemingly connected aspirations illustrate is a Haitian Tijuana in the making due to immigration bans and restrictions. Despite the impediments for social and economic advancement, the Haitian migrants verbalize their dreams, each showing that they are willing to settle in the city and earn a humane living presently impossible in Haiti.

Though obtaining Mexican citizenship is not as arduous as the discriminatory U.S. process that places quotas on racialized migration, theologian Paul Ladouceur remarks in the film Waylaid in Tijuana that, “The most urgent need for the Haitian community in Tijuana is still legalization.”

A legal pathway would help them achieve their goals and fulfill their dreams, which could potentially get them closer to social mobility. Toward the end of the film, Ladouceur maintains that if Haitians were to be legalized in Mexico, “I believe, in five years, you’ll have Haitian doctors, Haitian nurses, you’ll have Haitians driving taxis and being part of everything.”

Another Haitian man, Ustin Pascal Dubuisson, echoes similar ideas, “In five to ten years, the Haitian community will be part of Tijuana. We are already part of Tijuana, but in the future, it will be included more fully in the Mexican community. We will have more rights and will do more things.” While his words could fit within the framework of acculturation and integration, there is another possibility: His emphasis on the contributions of Haitian professionals to Tijuana gestures toward a diasporic community in the making of a global city that retains its connections to Haiti and acquaintances in the U.S.

There must be caution in avoiding romanticizing the idea of integration. Thinking through the lens of a Haitian Tijuana expands the parameters of identity and belonging in a city at the crossroads of imperial violence, colonial legacies, and diasporic belonging.

When Trump denigrated countries such as Haiti as “shithole” countries in 2018, perhaps he was projecting his own insecurities, while also describing the state of disarray of immigration policies under his administration.

In recent years, images of trauma and containment proliferate our screens, affecting our own engagement and understanding with moving images. The lies of the authoritarian in power also extend to other Black communities in the U.S., such as the Sudanese. It is impossible to escape the scenes of mass displacement, as these show the west’s creation of deteriorating geopolitical situations in the Americas, Africa, and Southwest Asia. Though scholarship in cinema and media studies continues to engage with migration studies, it is vital to engage race as experienced in so-called “democratic” spaces. The experiences of Haitian migrants in Tijuana is a point in case that addresses how the nation-state disrupts the migration patterns of racialized displaced persons.

The films point to how documentary cinema can successfully visualize the experiences of Haitians. As Ayisyens start families, form communities, and open businesses such as restaurants, Tijuana could become a site that disavows the transborder racialization process and one in which les Ayiseyen Tijuanenses live in dignity.

¹ Though the focus of this essay centers displaced Haitians in Mexico, I must acknowledge the racist exclusion of Black Mexicans. In the Mexican nationalist imagination, the concept of mestizaje is contentious. Some Afro-Mexicans, scholars, and cultural workers point to how mestizaje erases the experiences and contributions of Indigenous and Black Mexicans. The essay does not aim to reify Mexico for its performance of granting political asylum to Haitians when in fact, Black Central Americans are also subject to racist and xenophobic vitriol as they try to make their way into the United States. Questions on Black racialization along nationality are too large to adequately address in this essay. A narrow focus permits a critique of the visual regimes of empire, colonialism, and extractive capitalism.

² A Department of Homeland Security report said that while the agents used excessive force, they didn’t whip anyone.

³ Mireille Rosello, Postcolonial Hospitality: The Immigrant as Guest (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2002),

⁴ Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987), 3.

⁵ Arjun Appadurai, Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

⁶ Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 151.

⁷ Tiffany Lethabo King, 151.

⁸ Refer to Tatiana Flores, “Latinidad is Cancelled.” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, Vol. 3, no. 3 (July 2021): 58-79.