How The Bronx Framed George Romero’s Modern Zombie

Few monsters have sunk their teeth into pop culture quite like the zombie. Originating in Haitian Vodou folklore, the undead have since evolved into the reanimated, flesh-eating corpses that now stagger, sprint, and swarm across comic book panels, blockbuster screens, and survival-horror games. Distinct from the zombi of Haitian tradition, where the dead are revived after burial and compelled to obey their reviver, modern interpretations depict zombies as ravenous creatures that devour fresh human bodies.

Modern audiences owe this menacing reinvention to George A. Romero, the Cuban-American filmmaker from the Bronx whose 1968 cult classic Night of the Living Dead transformed zombies from infected brain-eaters into a cinematic phenomenon that laid the blueprint that would define the genre as we know it today. From The Walking Dead to World War Z, these walkers, runners, and infected continue to captivate us, proving that few monsters stay dead for long.

When people think of Romero—the undisputed father of the modern zombie and iconic horror pioneer—they picture shambling undead hordes, graveyards, grim black-and-white terror, and a cinematic revolution born in Pittsburgh. But before Night of the Living Dead, one of the most influential horror films, changed film history, before the zombies, the satire, and social commentary, there was the Bronx. And the Bronx had everything to do with shaping the artist Romero became.

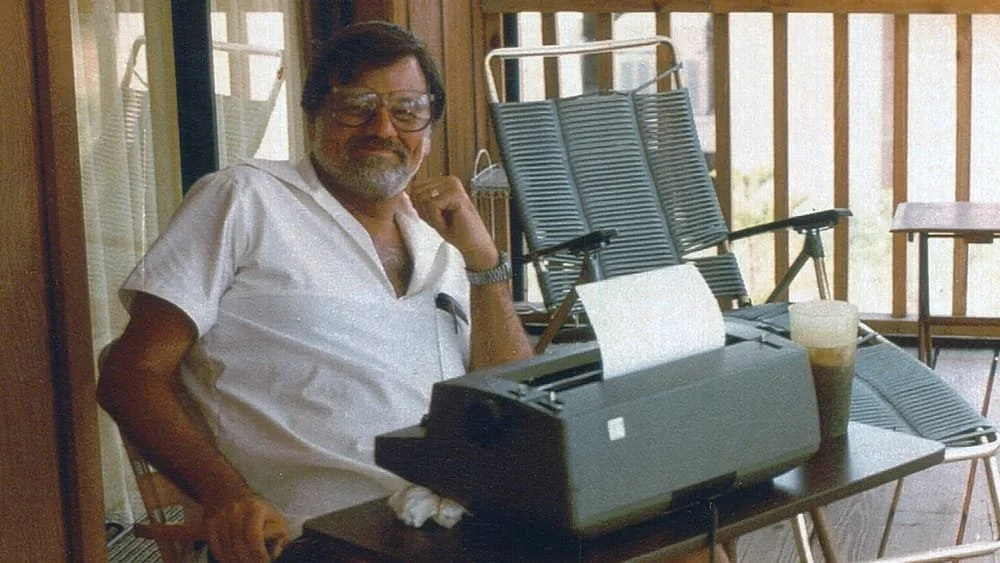

The Stay Scared!™ multimedia exhibition explores how influential the borough was for the filmmaker. Spread across three Bronx institutions—the Museum of Bronx History, the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, and the Bronx Music Hall—it traces Romero’s return to the borough that shaped him and the global horror genre he helped create. Through digitized archives, rare photos, posters, notes, screenplays, soundtracks, and behind-the-scenes material, the show reframes Romero as both a visionary filmmaker and a Bronx storyteller whose influence still defines film, TV, and games.

The exhibition highlights lesser-known chapters of Romero’s life—his childhood, unrealized film projects, and interests beyond horror—and is split into three sectors: his adolescence, his early career, and the creation of Night of the Living Dead.

Romero’s Bronx upbringing deeply shaped his worldview and his later use of horror as social commentary. Born in 1940 to a Cuban father and Lithuanian-American mother, he grew up in Parkchester, a working-class Bronx housing development that the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company built. Though marketed as modern and family-friendly, Parkchester enforced strict racial exclusions: Families of color were routinely denied rentals, creating an almost entirely white community until 1968.

Romero’s lighter-skinned Cuban family was able to move in, but he still faced hostility from his neighbors. Local Italian gangs, including the Golden Guineas, targeted him once they learned he wasn’t Italian, mirroring the broader racial tensions of the neighborhood. Family photos and neighborhood images from the period reflect this contrast between Parkchester’s calm surface and the harsh social realities that later fueled Romero’s filmmaking.

Cold War anxiety deeply influenced Romero’s imagination. Growing up in the late 1940s and 1950s, he was terrified by Catholic anti-communist propaganda at school and televised animations, including mainstream shows like Ed Sullivan, that depicted cities and bodies destroyed by nuclear attacks. He would listen for planes, convinced a bomb might hit his neighborhood. Artifacts like gas masks, helmets, and civil defense imagery in the exhibit reflect how this climate of fear shaped the visual and emotional world of his later apocalyptic films.

As a child, he grew fascinated with filmmaking, frequently watching films at local theaters. The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) first revealed the magic of cinematography to him, while horror films like The Thing From Another World (1951) and The Man From Planet X (1951), along with classics such as The Quiet Man (1952), On the Waterfront (1954), and The Ten Commandments (1956), also shaped his cinematic tastes.

Despite Romero listing “dentist” as his future career in his yearbook, filmmaking was alluring to him. Inspired by Tales of Hoffmann, he borrowed his uncle’s camera and spent summers at Uncle Monnie’s making films in Scarsdale. He joined the amateur group Herald Pictures and around 1954 made the sci-fi short The Man from the Meteor, which got him in trouble for tossing a flaming dummy off a roof.

Romero, a lifelong admirer of Edgar Allan Poe, drew inspiration from the poet's blend of beauty, fear, dread and melancholy. Poe influenced several of Romero’s projects, including unproduced scripts for The Masque of the Red Death and The Raven. In his dystopian take on The Masque of the Red Death, the wealthy isolate inside a fortified enclave to escape a plague, as gangs run the city outside, offering “protection” to the poor only in exchange for their enslavement.

At home and at school, Romero found escape through art. Racial tension, Cold War paranoia, a Catholic upbringing, and early creative play all fueled his commentary and supernatural fascination, laying the foundation that would tie real-world anxieties to the undead.

After graduating from St. Helena’s at only 16, Romero’s uncle, Harold Banks, encouraged him to spend a postgraduate year (1956–1957) at Suffield Academy. There, he discovered his direction, joining chess, glee, and drama clubs; cartooning and editing for school publications; creating the award-winning film A Study of the Earth (“Earthbottom”); founding the Ram Pictures film club; and helping produce a film partially shot in Cuba. He began signing his work as “George A. Romero” and decided to pursue film at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon).

Arriving in Pittsburgh in 1957, Romero connected with like-minded collaborators through art classes and community theater. Around 1960, he borrowed money from his uncle to make the unreleased comedy Expostulations. The following year, he and producer Russ Streiner founded The Latent Image, Inc. to produce commercials and documentaries.

Romero also cofounded Image Ten, a guerrilla filmmaking collective known for low-budget creativity. Archival materials such as stills, storyboards, and restored snapshots show the team creating scares through resourcefulness, a philosophy shaped by his Bronx-to-Pittsburgh journey. He believed horror should be accessible to all, not just studios, a vision that later inspired generations of filmmakers, game designers, and comic creators.

For example, Edwin Pagán, Stay Scared!™ cocurator, director, and founder-in-chief at Latin Horror, recalls being inspired by Dawn of the Dead. “When I watched Dawn of the Dead in 1978 at a local Bronx drive-in, I could not get enough of his ‘walking dead’ stories,” he says. “His subsequent canon of work mirrored the zeitgeist of times when the films were made, also making Romero a documentarian who embedded his narrative feature work with historical context.”

The final section of the exhibit takes viewers into the world of Night of the Living Dead, the film that rewrote the rules of horror. Although produced in Pittsburgh, the film’s social DNA—rooted in tension—traces directly to Romero’s upbringing. Shot with a small budget and local connections, the film consisted of a skeleton crew and friends as background actors.

Behind-the-scenes photos, newly digitized by archivist Ben Rubin, reveal the humanity on the set: the laughter, the exhaustion, the invention. There’s even a handwritten autograph that Romero signed with his trademark: “Stay Scared,” and the exhibit includes original props from the film, such as the dress worn by the woman who gets stabbed.

Although now hailed the “father of zombies,” Romero never set out to make zombie films. Night of the Living Dead didn't even use the word “zombie,” instead calling its undead “ghouls.” Romero acknowledges inspiration from E.C. Comics, Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, and possibly Cold War imagery, Poe and H.P. Lovecraft tales, depictions of addicts or POWs, and even the Jewish golem.

Romero’s career reached beyond horror. Alongside tributes from the filmmakers he inspired rare materials from lesser-known projects, including his unproduced Marvel script Mongrel: The Legend of Copperhead (cowritten with Jim Shooter in 1983) and sketches from his War of the Worlds adaptation. These pieces highlight the surprising range of his imagination.

Romero inspired many other artists, including Guillermo del Toro, who recalls their pen-pal friendship and how toward the end of his life Romero finally seemed to understand his tremendous influence, which moved him to tears. “He gave the world a mythology,” del Toro says in a clip in the exhibition curated that Dr. Steven Payne and Pagán curated. “And he never took enough credit for it.” Thanks to the Romero Foundation and the University of Pittsburgh archives, many of these unseen works are finally emerging.

From The Walking Dead and The Last of Us to films, comics, games, and even conventions in shopping malls (a nod to Romero’s Dawn of the Dead) exists because Romero defined today’s zombie culture. His ideas spread internationally across genres, shaping generations of filmmakers, including many Latinxs. The Romero Foundation continues to build on his legacy through the Face to Face initiative, which supports young creators. His story, like the zombie genre he built, is one of collaboration, community, and resilience.

The tribute exhibition presents Romero not just as a horror icon, but as the Bronx kid behind the myth. Romero left the Bronx, but its imprint never left him. Now, at last, the borough is honoring the hometown artist who transformed modern horror.

Stay Scared!™ is on view through June 2026.