Re-envisioning Alice Neel’s ‘Mercedes Arroyo’

In late April 1948, Juan Emmanuelli, a Puerto Rican organizer for the Communist Party of the U.S.A. (CPUSA) in El Barrio (then still also known as “Lower Harlem”—but rapidly expanding eastward), met up with a young man from the neighborhood. Unbeknownst to Emmanuelli, the man was an FBI informant. They walked together to an apartment at 21 E. 108th Street, which Emmanuelli told the informant was “one of our main ‘storage’ places in Harlem,” which “very few of our members know about.” They were greeted by “a girl named ALICE NEEL, who introduced me her mother, and ‘my husband,’ whose name is SAM BRODY.” Neel then handed them some copies of The Crime of El Fanguito, CPUSA Chairman William Z. Foster’s pamphlet denouncing the widespread misery he had recently witnessed in Puerto Rico’s slums. Unfamiliar with Neel’s work, the informant described the apartment as containing her paintings of “Harlem subjects.” He was able to identify just one: “MERCEDES ARROYO.”

Born Mercedes Romero in Carolina, Puerto Rico, in 1910, Arroyo migrated to New York City in 1927. She married Francisco Arroyo and had two children. He died in 1939. Arroyo worked as seamstress, an assembly line worker, and a typist. Among other accomplishments, she helped organize other Puerto Rican women in the textile industry in the late 1930s. In 1940, she was elected to the New York State Committee of the American Labor Party. In 1946, she became President of the Mutualista Obrera Puertorriqueña (a “lodge” of the International Workers’ Order or IWO), and was part of the national leadership of the Cervantes Fraternal Society (Spanish-speaking section of the IWO).

By 1951, she had joined the New York State Committee of the CPUSA. From 1952 to 1956, she also taught at the CPUSA-affiliated Frederick Douglass Education School and Jefferson School for Social Science. She was one of the best-known political and social leaders of New York’s Spanish-speaking progressive sphere, at the forefront of every major political and social initiative of the New York Puerto Rican community of the 1940s through mid-1950s.¹

And yet, aside from a handful of brief mentions by her contemporaries (for example, Joaquín Colón, Gilberto Gerena Valentín and Bernardo Vega’s unpublished memoirs), with few exceptions, next to nothing exists about her in written form. Alice Neel’s portrait of Arroyo is in many ways the strongest trace of the Black Puerto Rican Communist leader’s remarkable life readily available until now. Neel produced it during the high point of Arroyo’s own activism, a testament to its centrality in her story. In some ways, the portrait’s own history roughly parallels Arroyo’s, being exhibited repeatedly until about 1955 and then dropping away from sight, surfacing only very sporadically until the art world rediscovered Neel’s work.

The date of completion for the portrait is reportedly 1952. However, as the FBI informant’s report on Neel and Brody shows, it already existed at least four years earlier. Both the informant’s ability to identify its subject and the fact that her name seems to serve the function of underscoring Neel and Brody’s membership in the party—this is the first and earliest dated item in Brody’s 238-page file, which was closed in 1964—indicate Arroyo’s prominence in the community, as well as confirming her own status as a subject of surveillance.²

Perhaps more importantly, even if the informant was exaggerating the secrecy and importance of the visit, it reveals an extent to Neel’s involvement in Communist Party activities in El Barrio that is often downplayed. While she often complained that the party “gives her nothing more important to do than pass out leaflets and paint signs,”³ the use of her home as a hub for the storage and distribution of party literature seems a larger responsibility than merely handing it out at demonstrations.

In turn, this challenges the usual assumptions about Neel’s relationship with Arroyo, who was not simply some exotic “ethnic” neighbor who stirred up the artist’s curiosity and humanist sensibilities. In fact, they were not neighbors at all: although Arroyo lived on 109th Street, just one block to the north, she was all the way across town in Manhattan Valley, which became heavily Puerto Rican in the late 1940s (on the West side of Manhattan, between Columbus and Manhattan Avenues).⁴ East Harlem was the major focus of Arroyo’s political work, not the neighborhood where she lived. Arroyo and Neel’s relationship, therefore, in addition to any elements of friendship it may have (likely) had, was between two committed radical militants—with Arroyo occupying the higher rank.

On December 26, 1950, an exhibit of Neel’s work opened at the American Contemporary Art (ACA) Gallery in Chelsea, in a one-person show featuring 17 paintings, including “Mercedes Arroyo.”⁵ The renowned writer Mike Gold, also a party member and friend of Neel’s, reviewed the show in his regular Daily Worker column, titled “Change the World,” the following day. Praising Neel’s Social Realist style (which by now was quickly falling out of vogue in the mainstream art scene), he noted that “[i]ncluded among her portraits are one of Mercedes [Arroyo]” whom he described as “a trade union leader of the Puerto Rican people” who was “well-known for her heroism.”⁶ While “leader of the Puerto Rican people” was the paper’s standard tagline for Arroyo, the qualifier “trade union” suggests she may have still been active in the labor movement. The adjective “well-known,” as well as the fact that Gold singled out her portrait in his review, indicates she enjoyed some notoriety and status with his readers. However, the emphasis on her “heroism” is one of the few descriptions of her character that are available anywhere, and it underscores the personal risks and sacrifices that accompanied her rise to prominence among the left as well as the broader Puerto Rican community during the previous decade.

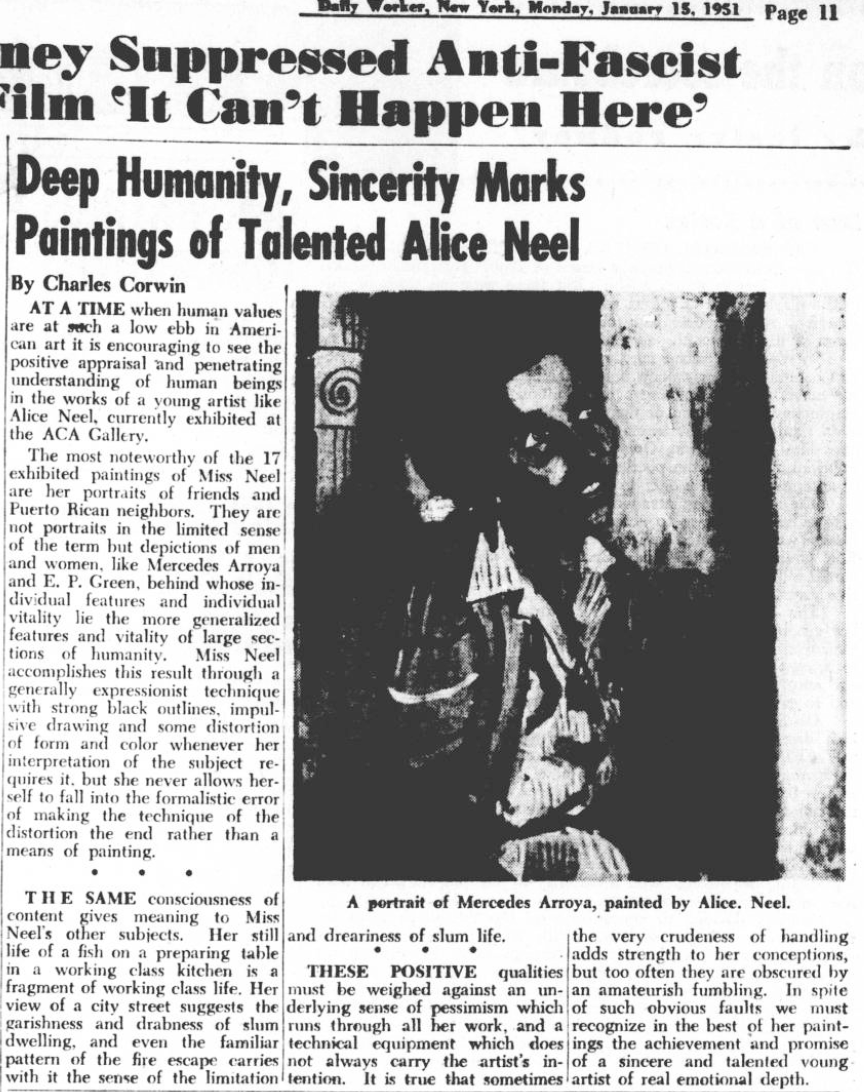

The show’s review in the relatively apolitical Arts Digest likewise also highlighted “Mercedes [Arroyo]”, mistakenly describing the latter’s subject as “a neighbor” of Neel’s. The author described the portrait as “another top-drawer,” with Neel’s depiction of Mercedes’s hands, “as usual in her work, strong, well-realized and well-painted.”⁷ Another review of the same show by Charles Corwin, published two weeks later in the Daily Worker, includes a photograph of the painting, leaving no doubt that this is in fact the same portrait of Arroyo by Alice Neel that has been exhibited in recent years. Corwin’s review notes that Neel’s works are “not portraits in the limited sense of the term, but depictions of men and women, like Mercedes [Arroyo] and E. P. Green, behind whose individual features and individual vitality lie the more generalized features and vitality of large sections of humanity.”⁸

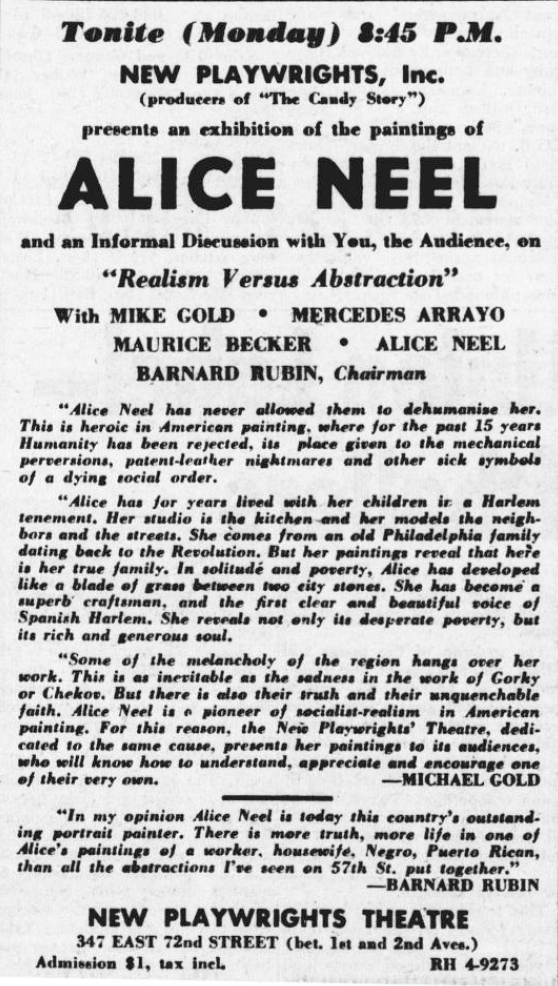

Neel’s “Mercedes Arroyo” was exhibited (at least) two more times in New York City during the 1950s, at the New Playwrights’ Theatre on East 72nd St., which opened on April 23, 1951,⁹ and at the Art of Today Gallery on 57th St. and 6th Ave, in early May 1955.¹⁰

Whether or not she was present at the other exhibitions, Arroyo attended the opening of the exhibit at the New Playwrights’ Theater. In press advertisements of the event, she was billed as one of the speakers in an “informal discussion” with the audience on the topic of “Realism Versus Abstraction.”¹¹ While it is likely that all speakers articulated something akin to the “diatribe against abstraction” and “paean to Social Realism” articulated by Gold in his introduction to the show’s brochure¹²—this was the standard party line on art at the time—to include Arroyo on the panel (the only other woman besides Neel) suggests that Neel (and the others) saw her not simply the subject of her art but as an interlocutor. It also adds a certain aesthetic sensibility as a further dimension to her character, beyond community organizing and even politics.

According to Neel’s biographer Phoebe Hoban, the insistence in describing her work as Social Realism, just as Abstract Expressionism was taking off, marked her as “terminally passé” and ensured she would only have one more exhibit before the end of the decade.¹³ In fact, she had at least two: another show at the ACA Gallery in 1954,¹⁴ and the 1955 showing at the Art of Today Gallery, where she was just one among a long list of leftist artists showcased.

While it’s not certain whether more of her work was exhibited there, it is significant that the only one mentioned in David Platt’s review of the show in the Daily Worker was her “portrait of the Puerto Rican workingclass woman leader Mercedes Arroyo,” in which Platt sees “that unforgettable, poignant quality that is characteristic of all [Neel’s] work.”[15] It is possible that it was the only one of Neel’s paintings shown, selected by the artist as the most representative or significant of her recent pieces—which contrasts starkly with its virtual absence in Hoban’s biography, as well as the generalized lack of academic interest in Arroyo herself.

¹ These and other details of her personal and political life are findings in an ongoing investigation, to be published in forthcoming pieces.

² Neel’s was closed in 1961 (Hoban 2010: 222), and Arroyo’s over a year after her death in July 1964 (informal communication, National Archives and Records Administration, 3/27/2025).

³ Hoban, Phoebe. 2010. Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty. New York: St. Martin’s Press. p. 222.

⁴ Numerous documents dated as early as 1946 list Arroyo’s address as 63 West 109th Street. Jesús Colón Papers, Center for Puerto Rican Studies. Her descendants have confirmed this was still the address where she resided when she and her aunt Lucía were killed by a suspicious fire on July 8, 1964 (informal communication, 4/15/2025).

⁵ Mike Gold, “Alice Neel Paints Scenes and Portraits from Life in Harlem,” Daily Worker, 12/27/1950, pg. 11.

⁶ Gold, op. cit. See also Hoban 2010: 212.

⁷ N.L., “Alice Neel,” Arts Digest 1/1/1951, pg. 17.

⁸ Charles Corwin, “Deep Humanity, Sincerity Marks Paintings of Talented Alice Neel,” Daily Worker, 1/15/1951, pg. 11.

⁹ New Playwrights Theater, Advertisement, Daily Worker, 4/23/1951, pg. 11. See also FBI file on Barnard Rubin, 5/1/1951, pg. 26.

¹⁰ David Platt, “Who's Who of American Art In One Magnificent Exhibit,” Daily Worker, 5/5/1955, pg. 6.

¹¹ New Playwrights, op. Cit.

¹² Hoban 2010: 214.

¹³ Hoban 2010: 215.

¹⁴ Hoban 2010: 222.

¹⁵ Platt, op. cit.