Abstraction as Alienation: On Virginia Jaramillo’s First Solo Museum Retrospective at 83

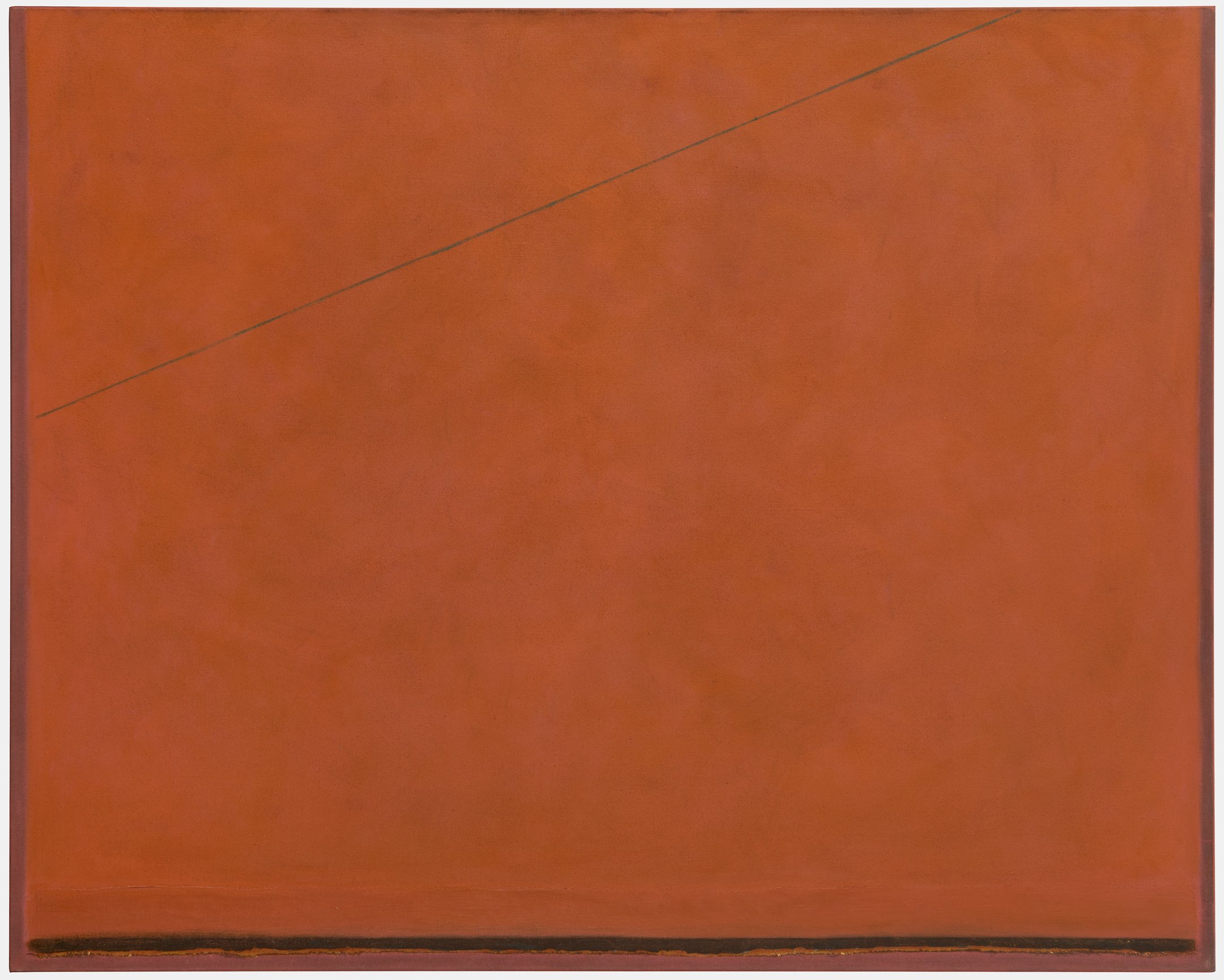

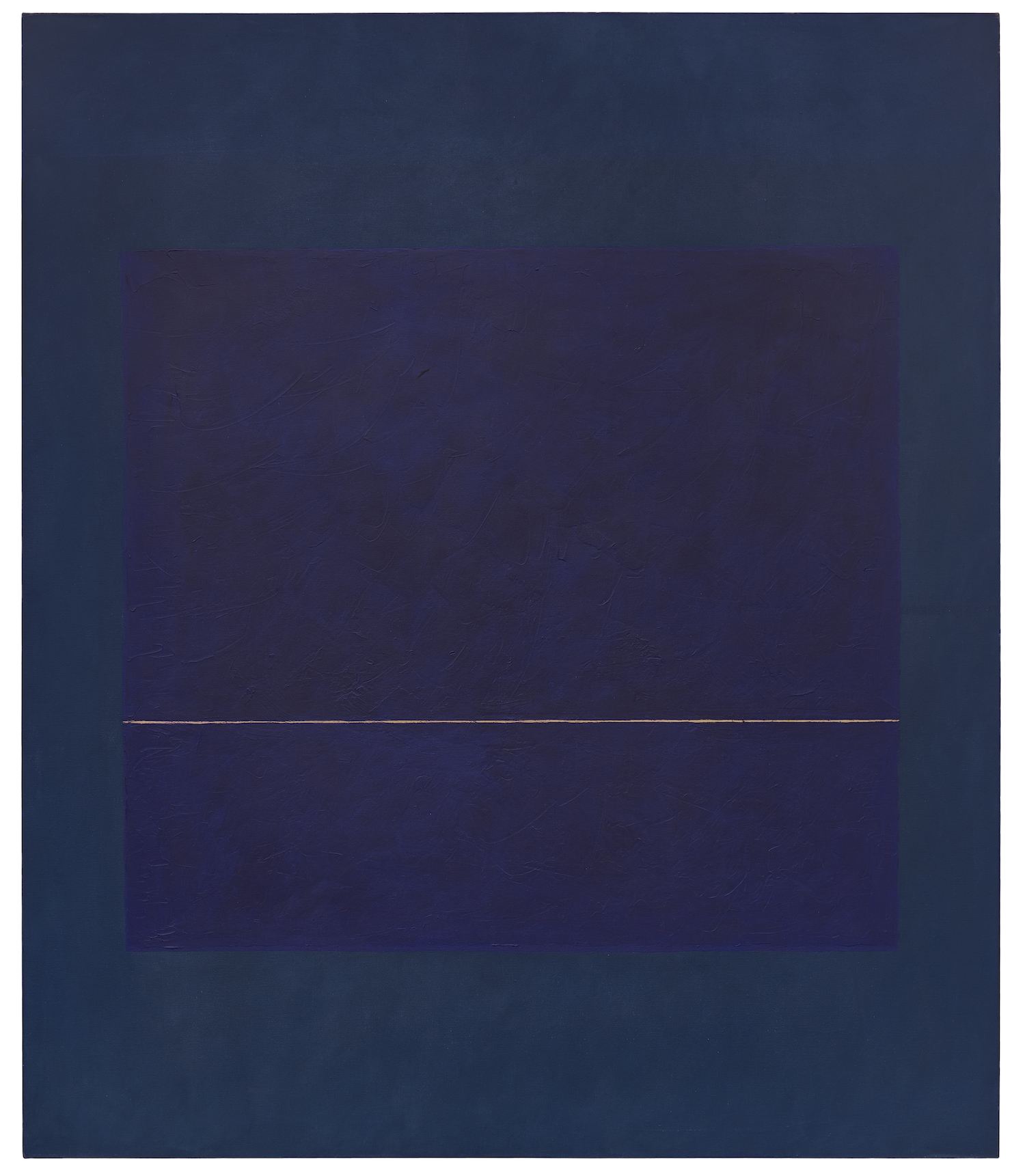

As a young girl, Virginia Jaramillo (b. 1939, El Paso, Texas) imagined herself becoming an archaeologist who sifted through layers of earth to find geological treasures. During summer visits to Imperial Valley, California, she’d squint below her bicycle at the cracked floor of the desert and wonder about the planet’s foundations. Her tectonic fascination grew in her teenage years as she voraciously read pulp sci-fi magazines. And when she began painting in the late 1950s, her work built upon her investigation of surface and the structural nature of space. Today, as a distinguished artist with a nearly 70-year career in abstraction, Jaramillo is still guided by those initial curiosities about the earth and its capacity.

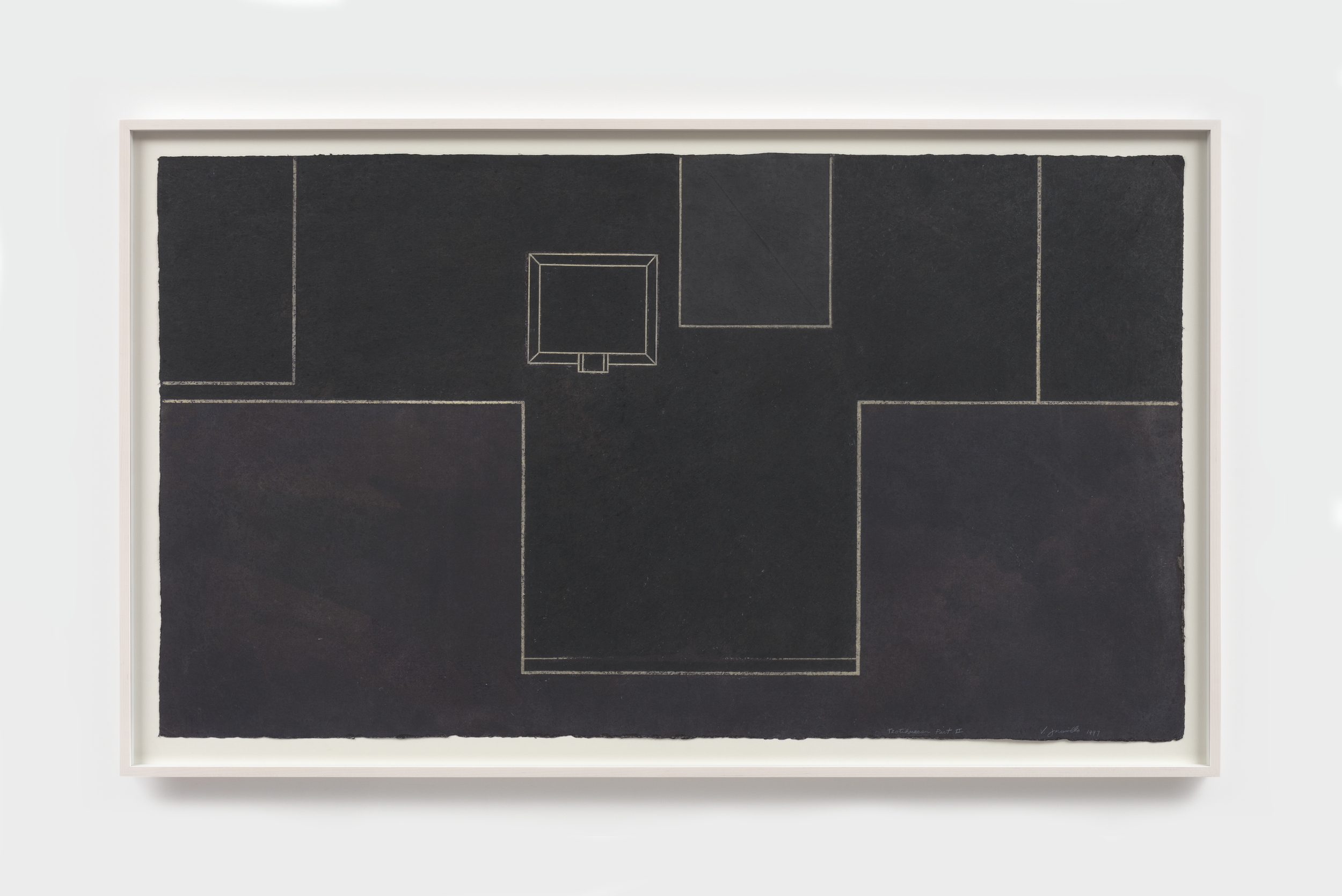

At 83 years old, Jaramillo will open her first retrospective, Principle of Equivalence, on June 1, 2023 in Kansas City at the Kemper Museum. Like many other women artists of color, the recognition of her contribution to art history and particularly American abstraction is long overdue. The show will include 73 paintings and many handmade paper works culled from institutions and private collections internationally. It is important to consider her art historical achievements as a Mexican-American woman who began making work in the 1950s. From my extensive research, she was the first Mexican-American woman to exhibit abstract works in a U.S. museum. She was also the only woman included in one of the first racially-integrated shows in the U.S.—The De Luxe Show in Houston, Texas in 1971.

There are several reasons why the intersections of her identity as a woman, a Mexican-American, and an abstractionist from her generation are important. First, there is insufficient but much-needed analysis and discussion about the “pigeonholing” artists of color experience concerning their medium and content. Second, we are currently experiencing a de-politicization of art and the whitewashing of art historical narratives. This removal of radical significance is happening alongside the DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) efforts many art institutions have taken up. Sometimes an artist’s life is political outside of the objects they make, and providing that context matters. As Jaramillo has said in many interviews, she lived her politics as a Mexican-American woman in an interracial marriage, with both parties intent on surviving as artists.

I first saw Jaramillo’s work in 2017 at Hales Gallery. The exhibition was titled Where the Heavens Touch the Earth. The gallery was dimly lit and overhead spotlights thrusted an incandescent glow encircling the works. I didn’t understand why I had never heard of an abstractionist of her caliber and background. For the next few years, I consumed all the writing and media on her, including an interview with Tyler Green on his podcast Modern Art Notes. I then filed her name into my mental database of art mothers—those who unswervingly pursue their truths despite money, ego, and other trappings of the art world.

In 2022, I was asked to submit a catalogue essay about her early life in California for her upcoming retrospective and immediately remembered that moment of recognition in Hales Gallery. Seeing Jaramillo’s Spanish surname, her Tejana background, and the fact she was an abstractionist, I had found an ancestral treasure.

Jaramillo pursued form, color, and texture in her work—an art genre widely known as abstraction. But why does it matter that a Mexican American artist began making abstract works in the 1950s? In his book 1971: A Year in the Life of Color art historian Darby English identifies the array of social, political, and psychological impetus for Black abstractionists despite many who believed otherwise. One of his thoughts is that through abstraction, the playful mind has full access to the imagination, which can be a form of liberation. English’s book foregrounds the previously mentioned group exhibit The De Luxe Show, in which Jaramillo was the only Latina artist on the roster. This mining of the imagination where one is not bound by structure, physics, or the bodily vessel is inherent in Jaramillo’s process. “I never had a preconceived idea. I would read phrases and one would strike a note and I would actually see a mental picture. Then, I’d work on that concept—or what I saw visually—for maybe weeks, even months, and then it would materialize as a work,” she said. She allows her mind to dig deep and explore the hidden and vestigial. There is power in leaving the figure and object behind and instead centering the theory or idea in a painting.

Because Jaramillo is an abstractionist, her Mexican-American background has tended to be omitted in scholarship or writings about her, what has been called a “whitewashing effect.” She is also not usually included in Latinx art historical round ups. There are several reasons I believe Jaramillo has not been invited to the Latinx BBQ. In an interview in 2022, I asked her why she thought she wasn’t included historically. She teased, “Well maybe it’s because I don’t do altars or clay figurines.” Couched in that critique is that Latinx art has come to be defined by its inclusion of a specific set of concerns and their visual representations: spirituality, ritual, immigration, family, Indigenous identity etc. If the art does not directly and literally reference these concerns, the identity of the artist is not considered relevant and, therefore, neutralized in the discussion of the work.

Identity politics and affiliations with social movements have defined the organizing principles of art history, especially for artists of color. There’s a reason identity-based shows like Latinx Abstract from 2021 are still being organized. We have to continue digging in the archives to identify those from similar backgrounds who led the way. Latinx artists and many other diasporic artists or artists of color are often kept out of art spaces unless their content or art practices legibly address a pre-defined, static set of concerns. Latinx artists who use the typical symbols of Latinidad in their work or make figurative paintings, political posters, perform or engage in social practice are more widely exhibited in art institutions. However, those mediums do not represent the full range of art made by artists who are Latinx as is the case for Jaramillo. I further address the failures of identity politics for Jaramillo in the exhibition catalogue for her upcoming retrospective.

Despite a lifetime of work and championing by colleagues like Mel Edwards and Frank Bowling, artists in the Black Arts Movement, Jaramillo will receive her first solo museum show at the age of 83. In 1970, Bowling wrote, “Virginia Jaramillo approaches her work with a certain verve which serves as a perfect antidote toward life situated in alienation.” Her practice of deep-thinking, meditation, study, and discipline, prepared her for the long wait. And she doesn’t have an inkling of resentment: “I just kept working.”

—

Virginia Jaramillo: Principle of Equivalence is on view at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art from June 1st, 2023 to August 26th, 2023. For more information, visit their website.

An exhibition catalog is also available for purchase from Yale University Press.

Barbara Calderón is a writer, artist and founding member of the arts collective Colectiva Cósmica. She is currently faculty and an art librarian at the School of Visual Arts. She was previously assistant director of The Latinx Project at NYU and has collaborated with the Brooklyn Museum on Frida: Appearances Can be Deceiving and Radical Women: Latin American Art 1960 - 1985 exhibitions. Her art criticism has been published by Art in America, The Brooklyn Rail, artnet, Art21, and Cultured Magazine. She was a recipient of the 2020 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.